Katembo shapes dialogue, and the nuances of language, identity and displacement ground Interlude with symbolic connections to home.

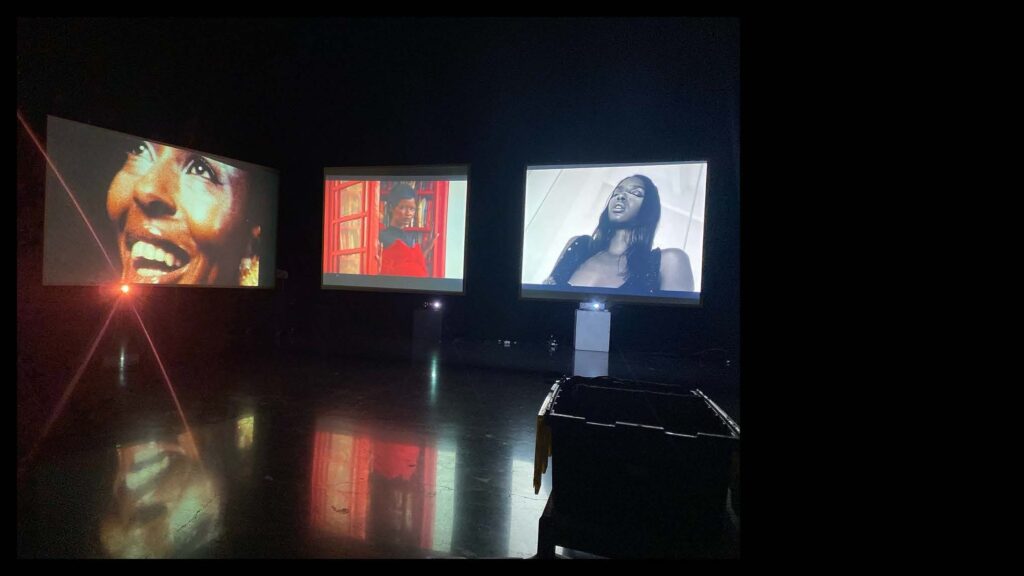

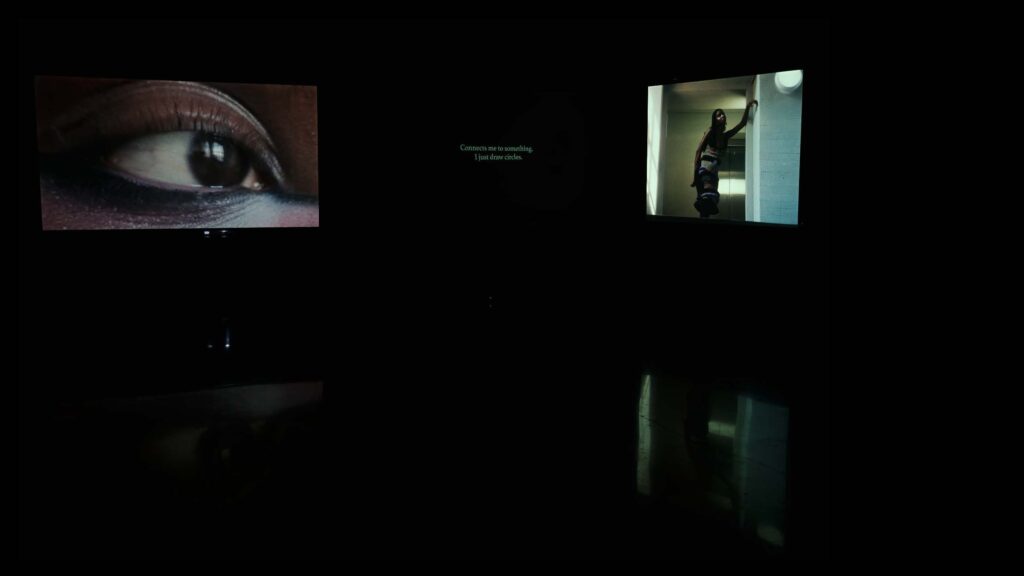

Upon walking into the black room with its soft lighting, strong eye contact and modelesque silhouettes, you notice five starry-eyed Black women staring at you from screens. A mystifying soundscape showcases lilting music by Montréal’s Hologramme unified by women’s narration in English, French, Lingala, Swahili, Kinyarwanda and Nuer. Presented on March 16, 2025, Rose Katembo’s solo exhibition, Interlude, is an immersive audio-visual experience.

Interlude was selected for the 43rd International Festival of Films on Art (FIFA). To finish her exhibit, Katembo was mentored by Angela Konrad, the artistic director at Usine C, a performing arts center in Montréal. The 15-minute-31-second video work conjures home by pointing to language as identity and a vessel for security and personal agency.

“Language is such a key element that sometimes we overlook when it comes to the experience of integration,” Katembo said. “Hearing more people talk about the situation in Congo gave me a bit more of a push to be like, kay, this is actually quite relevant.”

Nuances among language, identity and displacement ground Interlude with symbolic connections to home. Katembo spent her early adolescence as a refugee in Tanzania after her family fled the Democratic Republic of Congo to avoid the Second Congo War in 1998. When she was eight years old, her family was granted asylum in Canada, and they relocated to Montréal.

That’s where she learned English and French. At home, she stayed connected to her parents’ languages, Swahili and Lingala. To complete her exhibit, she channeled the belief that language can be both a bridge and a barrier.

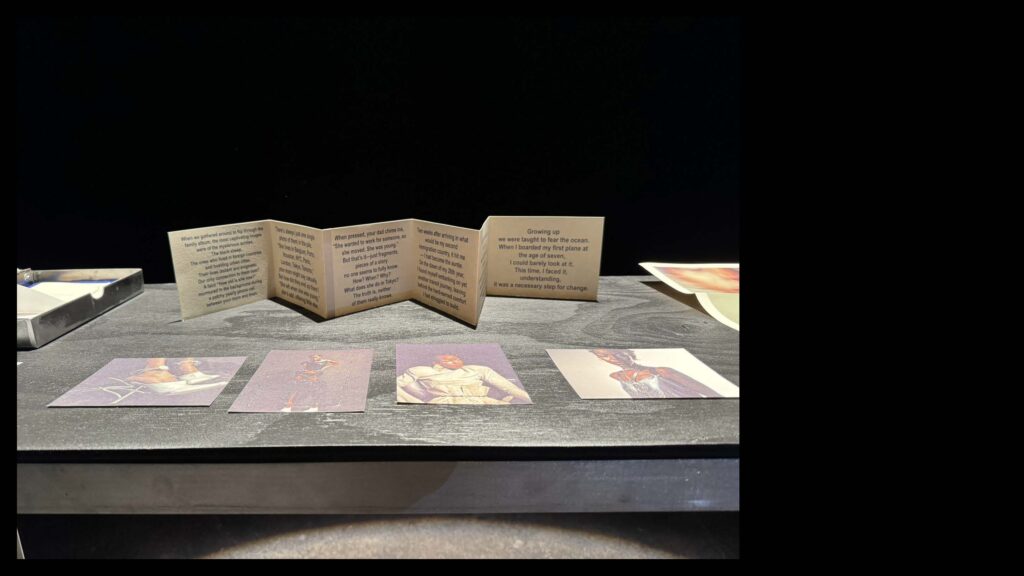

Interlude was born in 2022 from conceptual art photography. It’s a process-driven project intended to transcend language and create a visually explanatory narrative. She took inspiration from Cuban writer Gustavo Pérez Firmat, who examines the intersection of language and identity, American artist Cindy Sherman and Congolese artist Sammy Bolaji.

Katembo’s practice carries the lineage of Congolese discourse around the ingenuity of language. In one segment, Nas, which is named after its actress, five frames are dually exposed over Nas’s close-up. The separate frames can represent the multiplicity of identity. Each frame overlays the screen, then blinks out and refocuses on Nas, which shows how different positions can display nuanced perspectives.

Wrapped in displacement and extroversion, Interlude points to the process of self-unraveling, which is encouraged by lingual code-switching. Multiple exposures and overlays evoke a felt intimacy amid the multilingual soundscape, which establishes home by alluding to the intimate comfort in self-awareness despite projections and false perceptions of other people.

She mentioned travel as a way for Black people throughout the diaspora to expand their worldview. She believes that by highlighting intercultural similarities of Afro-diasporic people, they can connect with empathy and see each other more fully. Her sentiment echoes Pan-Africanism and the importance of understanding African diasporic history.

“Being an immigrant pushed me to be an artist and use art as a vessel for me to be able to translate something specific into something beautiful but that can have a lasting impact on people,” Katembo said. “That’s what I think is really interesting about art as a means of communicating my experience. I feel it’s an experience that is important for people to know whether you come from that same background or not.”

Since 1996, war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has caused the death of millions.

Wars in the Congo are the result of political unrest from the mid-20th century and vestiges of the Rwandan genocide in 1994. All of these conflicts have contributed to displacement, terror and instability in central Africa. According to the International Organization for Migration, about 6.9 million people have been internally displaced across 26 provinces since the start of the Rwandan Genocide (1994) and Congo Wars (1996 and 1998).

Displacement and Western exploitation are traumas that divide Afro-descendant people. Interlude directly reflects the trauma of displacement by encouraging immigrants to be present with their experience. It offers the use of language as a tool to thrive and hold personal identity during chaos and displacement.

A protective mask is a secondary artwork in the exhibit. The mask recreates the face of Esperance Kokonde, an Interlude actress. Katembo got the idea from watching films like Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Switching between languages evokes the idea of wearing a mask, which translates to the tools people must use for survival.

“Developing the mask was one of the key things for me for this installation,” Katembo said.

“She (Kokonde) told me that the second she left home, she had to wear a mask to make sure people could understand her, so the mask became a vessel for her to connect easily, and that’s also what language can be.”

Projects like Interlude showcase the potential strength of globalism. With resources like the internet, community is as close as a query, language is a leapable hurdle, and home is wherever you are.