“Travay ou voye’m lwen,” I instinctively said in our mother tongue to artist Didier William as we began to settle for a zoom interview. The English translation “your work takes me far” does not fully convey my intended expression. I kept repeating this phrase like a mantra emphasizing the last word. Lwen evoked both distance and dimension. And that dimension encompasses other levels, planes, and worlds. The multiverse. With the elongated pronunciation of the en, I knew he would recognize the contours of the vastness implied and get my meaning. As the saying popular among Haitians in the diaspora who lay claim to being natif natal or native born goes, Kreyòl palé, Kreyòl konprann or Creole spoken is Creole understood. This intimacy of language—a riff on insider knowledge—has the potential to open space for shared understanding from which we could engage in deeper dialogue.

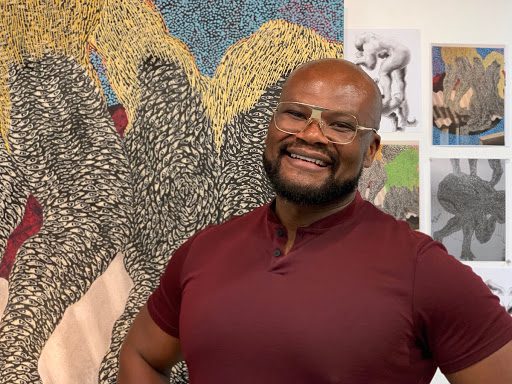

Above: Didier William

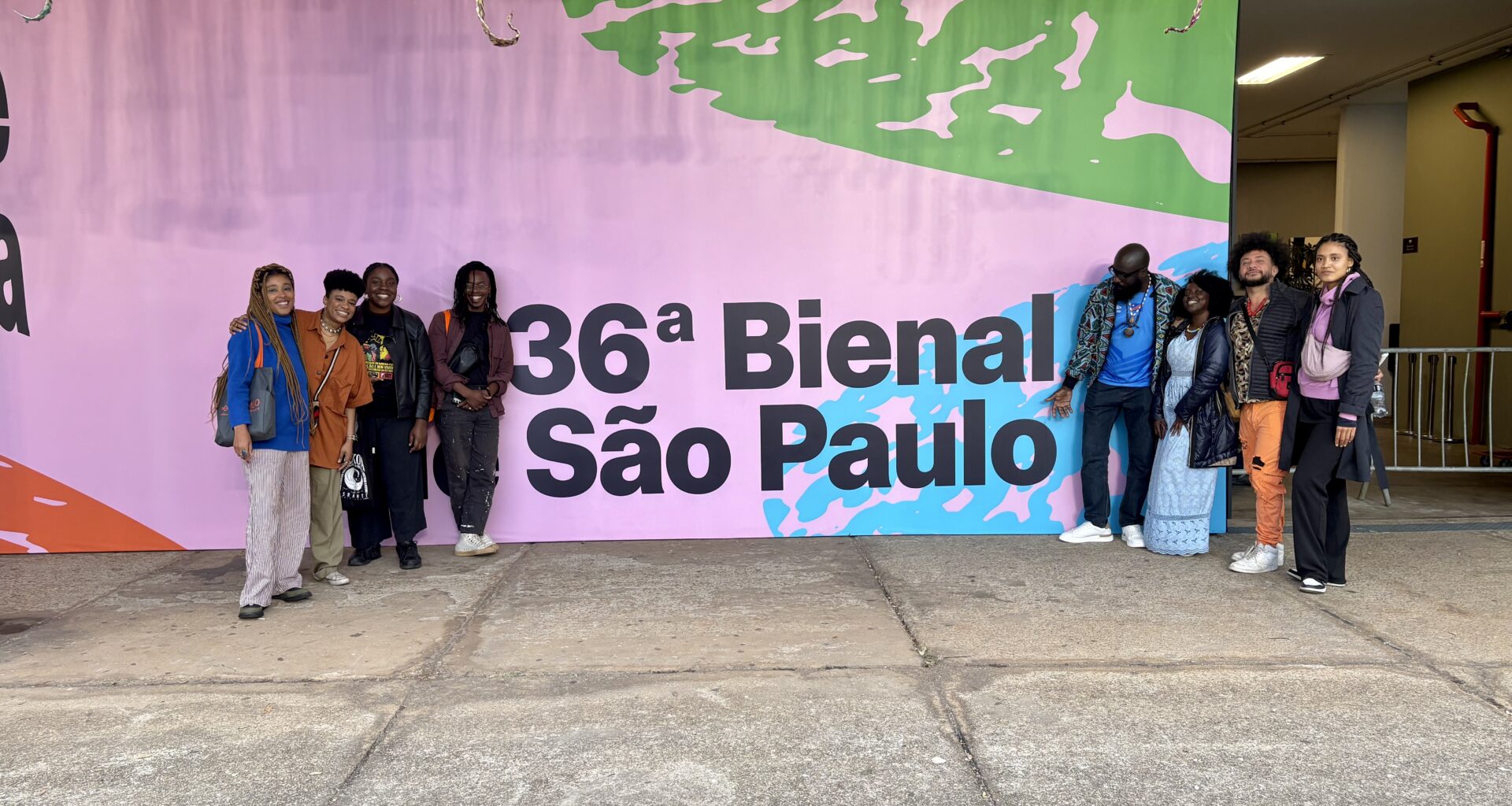

Our conversation, spearheaded by Sugarcane Magazine, concerns William’s latest exhibition. “Nou Kite Tout Sa Dèyè”, curated by Erica Moiah James, is the largest retrospective of his career. It is currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami just blocks from where he grew up upon his family migration from Haiti.

In awe of his work and command of spaciousness, I was eager to learn about William’s oeuvre and inspirations. My inclination was quickly overshadowed by curiosity, to go behind the scenes, stirred by the sensibilities of my ethnographic training, and a relatability (as a dyas–fellow immigrant, compatriot) to gain critical insight into the particularities of his embrace of an immigrant narrative with its complications. These have intensified in this specific moment as ravaged insecurity and political crisis reinforce the tumultuousness of life in Ayiti Cherie along with the fragility of democracy in our adopted country, the United States.

I don’t know William, and until he correctly reminded me, we had once met. My familiarity with his work came late though I vividly recall encountering the cover of Ezili’s Mirrors that featured his Ezili Toujours Konnenn (Ezili Always Knows) (2015). Multilayered, ornamental, and rich, Ezili lured me in with its floating heart vèvè, the all-seeing-eye or “the cut-through-eye-shaped forms”, the pig, and machete wielding babe associated with this escort of loa (Vodou spirit). Even in this compacted proportion, this painting was arresting. Characteristic of his work, it fostered an impulse to be deciphered with desire to not only make visual sense of the image and scene but demanded close and thorough inspection. This homage to the maitrès offers something familiar that is also unique. William uses, repurposes, and re-interprets what he calls “overlapping symbols” some associated with Haitian iconography as part of an extensive vocabulary with elements of the Black diaspora re-blended, to paraphrase the late-art historian, Robert Faris Thompson.

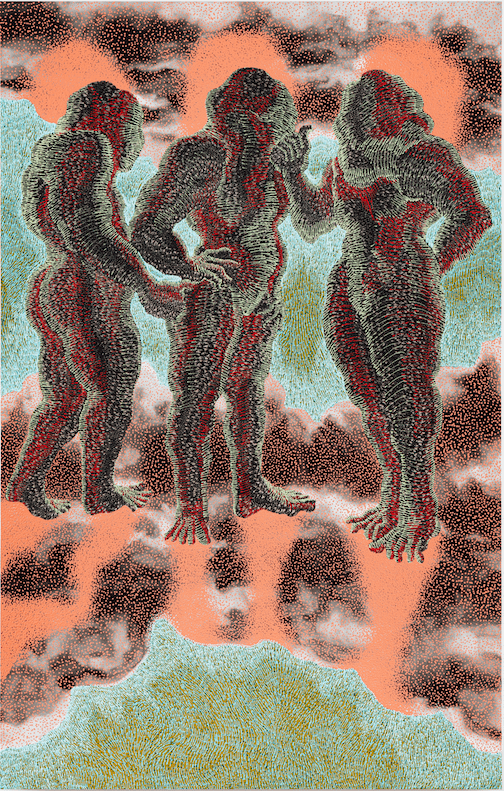

Opaque, and playful even when sinister, William’s work is quite distinct and has become instantly recognizable. Whimsicality and conviviality are on full display in “Mosaic Pool, Miami” (2021) as his beings confidently take space surrounded by bright tile design and lush tropical vegetation. That largeness is also in the congregation of Twa manman, twa kouwon (Three Mothers, Three Crowns) (2020). Firmly planted, they appear suspended while in deep contemplation. These paintings made of wood carving on panels captivate onlookers. Within the frames, there are multitudes of layers upon layers of vibrant colors, forms, subjects, textures, and themes that attest to his trained artistic skills and techniques, rebellious talent with an openness to be self-reflective and vulnerable.

Above: Didier William, Twa Manman, twa kouwon

This propensity to be self-referential is a break from personal and even professional norms that reveal William’s refusal of a “monolith Blackness” and staunch opposition to being artistically, discursively, and socially restricted. The art world tends to collapse identities. Williams who identifies as Haitian American, rightfully distinguishes himself from artists who live and produce work in Haiti. He is part of a cohort of artists and other creatives who have been navigating the hyphen and through their processes are redefining both concepts of Haitianness and what is deemed to be Haitian art. As the elder Miami-based artist Eduard Duval-Carrié explained, “there are three or four generations of Haitian artists who have evolved in the diaspora.” Indeed, it is well-known that William’s work stems from an imagination deeply rooted in his sense of self as a queer Haitian American immigrant who dwells comfortably within the gap between here and there or in what art historian, compatriot, Jerry Philogene calls “the beautiful condition of Diaspora.”

His ability to seek and find aesthetics in liminality through uprooting and re-grounding has been most generative for the prolific William who is making a professional return to the state where his artistic gift was first recognized, nurtured, and fomented. Currently based in the northeast, New Jersey to be precise, he is an Assistant Professor of Expanded Print at Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University. However, he has been quick to point out that this is not a homecoming. As he recently told the New York Times: “within the context of immigration, I don’t know that a homecoming is possible.” This survey, as he prefers to call it, for he is shy of forty years of age, is an excavation of still unfolding past.

Throughout his career, William has been contending with this historicity on different fronts from the ideological, to the personal, and political. For example, he specifically sought to explore gendered constructions: “I thought about masculinity in the bodies of two of the most important people to me; my husband and my father. My husband being a queer man and my father being this sort of emblem of a particular kind of Caribbean man.” The result was Two Dads (2017), which is not part of the show.

Among the forty works included in the exhibition is “Cursed Grounds: Louisiana Purchase” (2020) in which something wicked lurks in this dense landscape of the bayou part of the territory that France sold off to the United States as they faced defeat by the mostly enslaved population in 1803 Saint-Domingue. N’ap naje ansam, n’ap vole ansam: From Broken Skies Vertières (2019) a nod to that last battle of Haitian Revolution features three towering figures connected through their limbs in free fall. Art historian Jennifer Gonzalez, author of Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art (2008) immediately identified the cartographic timbers in this work. She noted the geographical elements with its map-like features, its blue sky and waters, “the bodies,” she emphasized “are like continents.”

As “floating signifiers,” his shapeshifting aliens are both “conveniently marked” as they resist racial categorization. They exist somewhere between Afropresentism and Afrofuturism. While they may be here, they take us to faraway lands, to other worlds. Writer Zoé Samudzi alluded to this in her essay, “Liberté, Egalité, Opacité” she wrote: “William is troubling the forward momentum of linear time. There is an element of surrealism to his abstractions, the bodies he illustrates, the bodies of Black people are disrupting and destabilizing space and time…” This is a common theme among Haitian surrealists from painters Hector Hippolite, Philome Obin, to Eduard Duval-Carrié, and textile artist Myrlande Constant. Their work, steeped in Vodou lexicon, took us on journeys. Whether spirits make an appearance or not, William’s work certainly takes us deeper, farther into new galaxies. That capacity to occupy both linear and all at once time is a burden and gift of visionaries.

As we talked, William expounded on what motivated and inspired him whether his subject is what was left behind (materiality) in the process of migration, what was brought on the voyage (memories, recipes, stories) to lot bò dlo, the other side of the water and most importantly what had to be forged anew (belonging and personhood) to make life here on this indigenous land mass many refer to as Haiti’s Tenth Department. His revelations exposed the symbiotic significance of negotiating what he refers to as an “adopted Blackness” and the impact of his tender relationship with family on his practice and becoming.

I wanted to know more about the unevenness, the gaps, the in-betweens of how the six-year-old Black Haitian kid whose family sold everything they owned moved to the U.S. decided to become an artist looks back on and is experiencing this moment of arrival. We didn’t quite get there because immigrant tales of Haitians in particular, tend to already be too formulaic in their presentation. As I have written elsewhere, in popular imagination, Haitians as a particular kind of Black have routinely been reduced to their conditions. As such, we have been trapped in archaic and stereotypical narratives that continue to obscure our plurality and realities. William who is hyperaware of this tendency and its impact rejects simplification and through his body of work has been redefining what it means to be a contemporary Haitian artist.

The title of the exhibition is a prime example. “Nou Kité Tout Sa Dèyè” is common refrain by Haitians to express detachment from their pays natal (birth country) as they settle to make life elsewhere. There is more than heartbreak. Something about the displacement creates intimacy with impermanence that necessitates forgetting. Speaking with measured clarity, William elaborated:

“Forget about it. Move on. We’re here now. This is your home get used to it. More and more as Erica and I spoke, it felt like [this phrase] was the title of the exhibition because not only was it signaling this kind of protective gesture that a lot of immigrants broadly Haitian immigrants specifically would sort of use to shield themselves from sort of pulling up this trauma, historical trauma. But it also signaled that there was this gap between here and there between present space and home that my work has been trying to fill this entire time. I think all the narratives and the anecdotes in my work, try to find spaces in that gap. These spaces where family members were lost or where items were forgotten or where homes were damaged or where failure happened or trauma happened or rupture happened. My paintings are in very different ways and significant ways trying to take those moments of rupture that exist in that gap and make them make sense, using the authority of image making that I have kind of called over the last 20 years.”

Above: Didier William, Just Us Three.

Rupture and trauma found articulations in the interstices of exigent landscapes, scenes, and massive figures that beckon onlookers to confront and engage themselves especially in the presence of his all-seeing eye–a motif he developed over a decade ago that has become a signature. Responding to the Trayvon Martin case, he began to carve out the eyes to return the too often dangerous and fatal gaze. This, he said, gave his painting agency. They eyes have since multiplied facilitating a flipping of the script on narratives of Blackness as the embodiment of the bête noir. The Black beast has been reappropriated, neither tamed nor wild, it is triumphantly looking back at the viewer!

At times, talking with William felt more like a meditation on presence. What still lingers is a lulling sense of comfort that emanated from deep within as he revisited his journey. An artist at peace whose subject often demands confrontation and introspection with the horrific, our basest of human instincts and the visceral. Far from linear, our conversation delved into the expected with his origin story. William’s response to the question did he always know he wanted to become an artist was a simple no, adding “the only other creative producer in our family is my mom.” When people ask him, “is there another artist in my family? He replies, “yes, my mom, she’s a chef, she’s a cook.” It’s easy to see his mother as his first muse given the profound influence she had on his creativity, a poignant reminder of the importance of models in an artist’s life–shoutout to writer Alice Walker. William stressed that his association of artmaking as alchemy comes from observing his mother. He paid loving tribute to her in a detailed recollection:

“She was the first person I saw do that was my mom.” He explained her impact further, “I grew up watching her take random stuff and turn it into magic… She took mundane things, minimal things, and turned them into things that smelled and tasted phenomenal. Our house always smelled like amazing food. I think watching her do that, I wanted to do that, but I didn’t want to do it with food. I wanted to do it with paint and paper and wood and burlap and plaster and charcoal, um, and, and plastic and, and, you know, linoleum and nylon. I wanted to do it with material, but it’s the same tactility. It’s the same sort of sensuous, um… dexterity that my mom takes peppers and onions and rice and meat, the same thing she does with her hands there, I do with my hands here in the studio. That always made sense to me. I didn’t know that could become a career, but it always made, it always felt right.”

That rightness to do and make things with a propensity to dabble was apparent in the third grade at Little River Middle School. William who remembers his teacher Judy Williamson by name said that she was impressed with his work during art hour, she called his mom in and told her that I had talent. She told my mom there’s this school, in south Miami that has a magnet art program. The New World School of the Arts would give him the opportunity fulfilling his academic requirements in the morning and focus on art in the afternoons. Both of his parents were fully supportive. “Years later, when I told them, I wanted to be an artist and they said, how can we help?” Of course, he went on to earn his MFA in painting and printmaking at Yale University School of art. Still, I was amazed as he underscored the anomaly of their response compared to scary and discouraging tales of immigrant parents (mine included) who demand their children become doctors, lawyers or select a profession that makes money.

We agreed his parents are unicorns. Rare and deeply appreciated. Their unwavering support has not stopped. When he came out to them as gay, directly afterwards they said, where’s our grandkids? But it is a fact that he was completely nurtured. William affectionately recognizes the primary role of his mom who was orphaned at a young age yet was determined to support her children against adversity. Family provided him with what the late feminist bell hooks called a homeplace—a hope filled setting, with love and support to endure and overcome, where we can recover ourselves.

Overcome, they did because re-making home in the diaspora had its share of tribulations. There were limits to its comforts because the beautiful condition of diaspora had to be made. This rebuilding of one’s foundation requires agency to be cultivated. Especially since, in the aftermath of disaster man-made or otherwise, our bodies become our archives. William exudes a sense of peace as he discusses his development. His potomitan—that central pillar used in ceremonies—is within. Ease came through admittance that it took him work to get here, to be at this point where he can look at the conditions and difficulties transform them with his art rather than let them define him. This constant dialogue is an exercise in mirroring that beholds what has been praised by collectors and critics as the artist’s universal appeal. Therein lies the alchemical in his work. Seeing, being and making oneself anew as continuous practice:

“To be an immigrant is to sort of submit yourself to the present. Um, and it is also to kind of admit to the fact that in a very specific way, part of your history has to make space for loss. And I think anyone who comes from an immigrant family or has immigrant parents, or is an immigrant themselves, can understand that there’s a kind of jettisoning of personal history that, must be contended with in order to look toward these other prospects. I think that’s a two-sided coin. Part of that is this conversation about loss, and then the other part of that is this conversation about presence where you really don’t have a choice in either you have to sort of come to the present moment and build a history that is living and breathing as you’re trying to contend with this new sort of adopted reality, which in my case was an adopted Blackness in the United States like adopting the United States history of Blackness and Black representation as I was trying to sort of contain and retain my ancestral history and relationship to Haiti.

That aspect of his immigrant narrative, which is as painful as it is typical, only complicates concepts of home especially when we expect wellbeing to be external. A participant-observer, this queer Haitian American artist has accepted the fact that living is in the between. Home is elusive. Malleable. Terrifying in this fast-changing world, without guarantees. Like his fierce, gigantic androgynous creatures, adept at defying gravity who are simultaneously as hefty as they are buoyant, the artist possesses aliveness with gravitas. Finding connection and source in the ephemeral on this long path to liberation is paramount. #WeWillWin. It is not surprising then that William asserts, “presence is the pinnacle of liberation…” He certainly knows only too well this as a privilege. “Having the opportunity to be present,” he mused, “is the most aspirational condition of what it means to be free… the opportunity to be fully present.” With his oeuvre, William issues an open invitation to be in spaciousness of far away and wider worlds somewhere between now and then, and here or there. In this moment, many of us are eagerly responding, Nou La.

Bio: Gina Athena Ulysse is Professor of Feminist Studies at University of California, Santa Cruz.