The brutality of the Jim Crow era is well known to most. The casual terror unleashed on black bodies and psyches through lynchings and beatings still echoes loudly through our collective memory, even for those who were born under the first black president. So many of us can recite a litany of names of the martyred: Medgar Evers, Emmett Till, Martin Luther King, Jr., and so many more.

But what about Recy Taylor? What about the brutal rape she endured?

If you’ve never heard of her, that’s understandable. If her name does ring a bell, it’s likely because Oprah mentioned her while accepting the Cecil B. DeMille award at the 2018 Golden Globes Awards ceremony. During the landmark speech, Winfrey invoked Taylor as an unheralded champion of the civil rights movement, one whose name should be known by all. Thanks in large part to a new documentary, The Rape of Recy Taylor by director Nancy Buirski, Taylor’s story is finally being told.

One night in 1944 in Abbeville, Alabama, Taylor was walking home from church when she was abducted at gunpoint by six white men. They raped her and left her blindfolded at the side of a desolate road. Although the rape of black women at the hands of white men was common at the time, these horrific acts didn’t receive nearly the same degree of attention as other racially-motivated crimes. The numbers are staggering, far beyond what most of us have ever considered.

“The public lynchings that took place during Jim Crow were public for a reason: they were being used as a way to remind people how to behave,” says Buiriski. “These rapes had a different power dynamic; This resulted from a systemic culture and belief that men had the right to women’s bodies that goes back to slavery. People didn’t make a big deal about it because it wasn’t exceptional in the minds of the white men who raped at will, and black women were brought up to feel it was something they had to accept. That’s what is so exceptional about Recy Taylor; she knew what these boys did was a crime and she spoke out immediately.”

The revelatory documentary charts the long fight that unfolded after Taylor’s unprecedented decision to seek justice. The film plays like an elegy, drawing on interviews conducted with Taylor’s friends, relatives and briefly Taylor herself—all of whom are now deceased—and is interspersed with haunting footage from “race movies”, films made by black directors at the time that served as some of the only public outlets in which these savage rapes could be depicted and discussed. Throughout, mournful variations on Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth” score shots of the fog-draped south, burdened with secrets and sin.

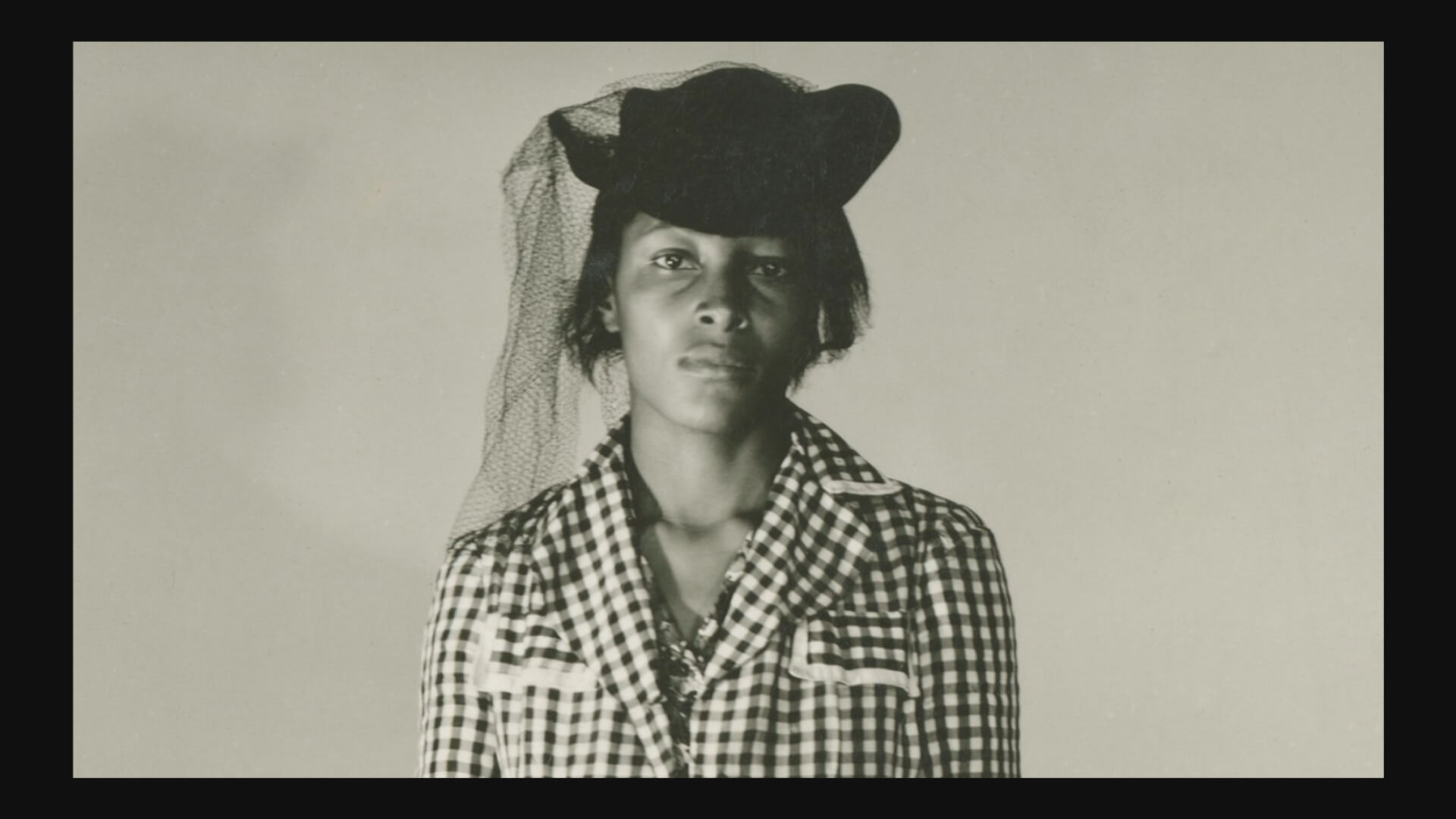

Above: A group of civil rights workers.

In laying out the details of this little-known story, the film also reveals that none other than Rosa Parks spearheaded the campaign to bring Taylor’s rapists to justice. A decade before she became a civil rights icon during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Parks was the lead rape investigator for the NAACP. The film explores how she was dispatched to tackle Taylor’s case, confronted relentless oppression from local authorities in her investigation, and just how her work led to the establishment of the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor. These efforts brought attention to Taylor’s story in black newspapers around the country, forming a network that would be of increasing importance as the fight for civil rights intensified.

“Our film tells that story about the power African-American women had in politics, and how they became in many ways the origin story of the civil rights movement,” says Buirski. “The groups that were formed in churches, especially around Recy Taylor to get her justice, are such an important part of the culture of African-American women, and that’s a big part of what we’re seeing even today.”

The documentary was released in December 2017, just two weeks before Taylor passed away. Though she would never find justice in the court system, the documentary ensures that her story is reaching a wider audience than ever before. The film’s release also came just before the historic election which prevented the controversial Judge Roy Moore from winning the U.S. Senate seat in Alabama. During the campaign, allegations that Moore sexually assaulted a teenage girl surfaced, as well as a long history of racist views, revelations which made it clear that he was cut from the same cloth as his fellow Alabamans who raped Taylor or fought to suppress her battle for justice.

“We did show the film a few days before the Senate vote in Birmingham,” says Buirski. “I can’t say it turned the tide, but there was a direct correlation between the defeat of Roy Moore and the number of African-American women who showed up and voted against him.”

What’s more, the film lands at a time when the intertwined oppressions of racial and sexual violence are being confronted with new vigor, making Taylor’s story more relevant than ever.

“While making this, there was no way to anticipate that there would be such a seismic change in our discussion about these issues right now,” says Buirski. “One of the things you do when you make a film like this is hope that it may help spark a discussion. I’m glad that’s happening. When I make a film like this, I don’t see it as history; I see it as reality reconsidered.”

For more information on how to attend or host a screening, visit therapeofrecytaylor.com