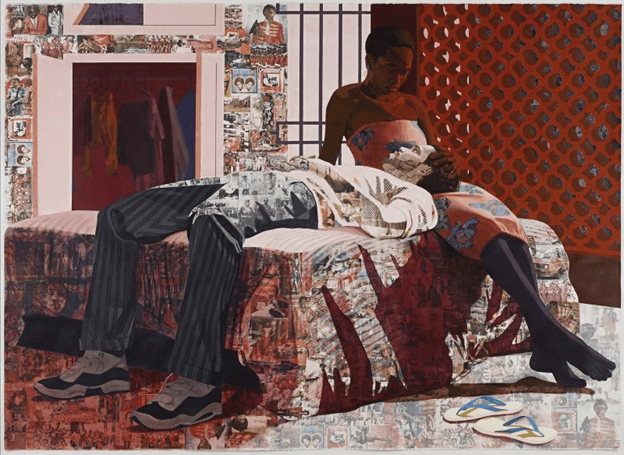

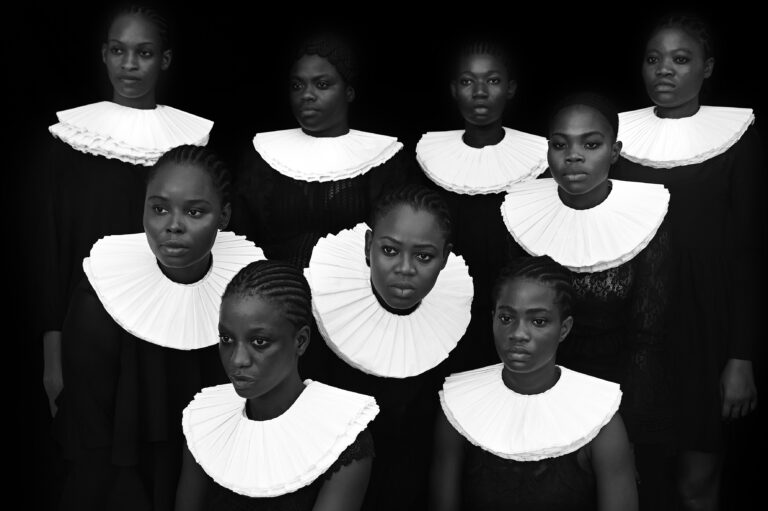

Work by Beverly Buchanan, Elizabeth Catlett, Sonya Clark, Renee Cox, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Karon Davis, Minnie Evans, Nona Faustine, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Ellen Gallagher, Leslie Hewitt, Clementine Hunter, Steffani Jemison, Jennie C. Jones, Simone Leigh, Julie Mehretu, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Senga Nengudi, Lorraine O’Grady, Sondra Perry, Howardena Pindell, Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, Joyce J. Scott, Emmer Sewell, Ntozake Shange, Xaviera Simmons, Lorna Simpson, Shinique Smith, Renee Stout, Mickalene Thomas, Alma Woodsey Thomas, Rosie Lee Tompkins, Kara Walker, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Carrie Mae Weems and Brenna Youngblood.

Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles, is proud to present POWER, an exhibition curated by Todd Levin that surveys the work of African American women artists from the nineteenth century to now. Titled after the 1970 gospel song by Sister Gertrude Morgan, the exhibition begins with artists born soon after the Civil War and continues to the present, weaving together fine and folk art traditions to explore how artists have engaged issues of race, gender, and class against our evolving cultural and artistic landscape. The 37 artists in POWER draw into focus their struggle to establish themselves as equal players on the uneven field of the American republic.

The exhibition traces two artistic threads that entwined to produce groundbreaking and evocative works across a range of mediums, which continue to influence artistic dialogue today. The first approach, rooted in American history from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, grew out of the horrific repression of slavery, when little formal education was available to black people living in the United States. Americans of African descent—and particularly black women—managed to preserve the culture of their ancestry, often at their own peril, by passing their histories down through craft-based folk traditions.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as access to art academies broadened, a growing number of black women artists emerged in the wake of the Reconstruction Era, including Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Alma Woodsey Thomas, and Elizabeth Catlett. With formal study in the traditional atelier model still dominated by white male artists, they produced works that inventively reflected and adapted the modernist art historical developments of the time.

These two paths of self-taught forebears and a newer academically trained generation collided at the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s. During this period, African American women began to “dream in color”—to envision a world in which their view of the human condition would be included in artistic dialogues, and within the greater American experience. Still, except for few exceptions, the work of black women remained far more neglected and forgotten than even their black male colleagues.

It was not until the momentous strides of the Civil Rights and Women’s Movements of the 1960s and 1970s that new openings arose for more voices to join and shift contemporary artistic dialogues. Artists such as Betye Saar, Faith Ringgold, and Lorraine O’Grady produced unforgettable images of resistance and community that incorporated both modernist tropes and the continued importance of vernacular artistic traditions. They gradually received increased attention from arts institutions, paving the way for the following generation to break further ground in the fields of photography, sculpture, and performance. Works by Senga Nengudi, Carrie Mae Weems, and Beverly Buchanan, for example, demonstrate the varied mediums and approaches that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the rich and extremely varied body of work created by African American women artists continues to blend folk traditions with contemporary artistic theories and practices. Across all mediums, including painting, sculpture, photography, and video, artists such as Ellen Gallagher, Kara Walker, Mickalene Thomas, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and Nona Faustine break new ground, activate age-old traditions, incorporate new technologies, and look resolutely towards the future.

POWER will also include an installation of over one hundred African American vernacular photographs from the early twentieth century on loan from the Ralph DeLuca Collection. They offer a diverse view into everyday lives of African American women, from images of positive change to difficult scenes of negative stereotyping and violence. Offered as an exhibition-within-an-exhibition, these images from a century ago encourage reflection upon the continued struggles of black lives in America today.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a publication with a specially commissioned essay by the critic and scholar Andrianna Campbell.

Sprüth Magers Los Aangeles presents Power: Work by African American women from the nineteenth century to now