Walk through life Beautiful more than anything Stand in the sunlight Walk through life Love all the things That make you strong, Be lovers, be anything For all the people of Earth

-Amiri Baraka

Every generation has to grapple with the question, what kind of world do I want to live in. Aeronautics and astronautics physicist-turned-multidisciplinary-artist Autumn Breon creates immersive experiences that disrupt our collective ambivalence about oppressive systems. Her practice is a bold, critical fabulation that asserts Black culture with a vantage that surpasses the spectacle of exploitative stereotypes. She is inspired by the brilliance of scholar-changemakers like Adrian Piper, Bernice Robinson, Tricia Hersey, Christina Sharpe, The Network of Women, and Combahee River Collective. The tradition of abolition grounds her practice.

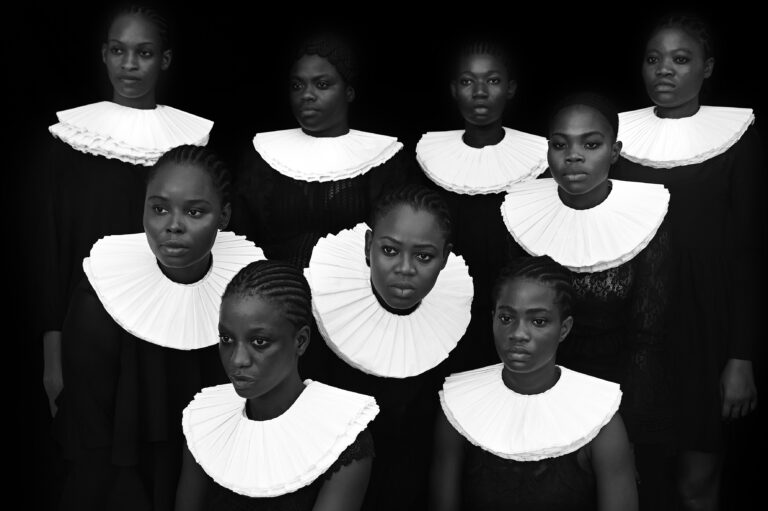

Journey with me back to Spring 2023 at Hauser and Wirth to remember, with great pride, the pageantry of Protective Style. Breon is “Deity,” a fly journey agent visiting planet Earth from the Astro black of Esoterica. She and her court cruise in the backseat of a low ride they call “Spacecraft.” The Black Fist Brass Band strides in steady procession alongside the crew.

Onlookers’ heads crane and bop in rhythmic accordance. This is a reverent vibe. A nod, touch, and agree communion. Breon’s hair is laid. White sheets of folded paper laden with demeaning terms, all confusedly used to describe Black women, are clipped like berets through her hair. So, when her caravan lands at The Esoterica Adornment Sanctuary, a site the unkeen eye could easily confuse for a beauty salon, we understand why.

Beauty salons are hallowed ground. Sanctuaries and institutions. Feel seen and be free assemblies—safe spaces for generations of Black women. In the sacredness of this space, Breon and her esteemed court call the names of genius civil rights activists, entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker and Bernice Robinson, and champion them as “Ministers of Adornment.”

“They are all protecting you and your scalp,” Breon reminds the crowd, “from the troublesome demons of your world with bits of protective styles that we drop off when we receive distress signals from your planet. You have many names for these earthly demons,” Breon continues, “sexism, homophobia, white delusion. In Esoterica, we call them distractions.”

How do we assess and design new systems if the distractions of crumbling ones burden us? How do we make enticing the work to imagine a transformed world? Esoterica is a metaphor for possibility and a call to action. Let Amiri Baraka tell it: “We are all beautiful, more than anything.” And didn’t Nina Simone talk about freedom, meaning no fear? Like them, Breon is rooted in the work of decoding broken systems and discovering what possibilities are there.

Women remain at the forefront of her data-driven analysis. Breon plays with myth and ritual to assess the ways systems work for or against our rights. In Worth the Weight, a powerful performance that troubles the power of stereotypes, Breon smashes bricks marked with slurs to bits with a golden sledgehammer. In Don’t Use Me, Breon reviews the ways race-based pay disparities disproportionately harm women of color.

She interviews Black and Palestinian refugee women and turns excerpts from their conversations into NFTs. The proceeds from those NFT sales went directly to those women, making them collaborators in new systems that disrupted ones negatively impacting their financial health. In We Are Here, a collaborative project with For Freedoms, Grand Park, and Kinfolk, Breon created an AR (augmented reality) and VR (virtual reality) monument in downtown Los Angeles honoring the late unsung heroine Bridget “Biddy” Mason. Mason was one of the first prominent landowners in L.A. and the founder of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Breon also has created performances and installations that confront the women’s reproductive rights crisis. In the traveling installation Care Machine, the artist fills a bright pink vending machine with free offerings and stations it in public spaces. Items distributed include tampons and pads, lube and hand sanitizer, candy and even “abortion pill” packs. Due to legal constraints that prevent some states from distributing actual abortion pills, the box has links to nationwide abortion services. Care Machine has been featured at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., Crenshaw Dairy Mart in Inglewood, Calif., and Prizm Art Fair in Miami. Next year, Care Machine will be included in a Get Out the Vote campaign.

Strong roots have solid branches, and Breon’s upbringing deeply informs her worldview. Breon was born in Los Angeles and raised by a family of migrants from Birmingham, Ala. who sought solace in the West from the Southern terrors of night riders and lynching threats. Her childhood was spent in Watts, Calif., and she grew up hearing stories about how her family thrived by defying the systems that could not see them as human. She was reared by gifted minds who labored as contractors and scientists, mathematicians and opera singers, and all exemplified an unwavering work ethic and a talent for music. Motherdear, her grandmother, an adept pianist, taught Breon how to read music and regularly escorted her to the library. While there, she encountered A Wrinkle in Time.

“And that was probably the first novel that made me think about science, specifically physics, as a career,” she noted during a conversation with me late last year. For Breon, spending time with her Motherdear encouraged expansive self-acceptance, exploration, and play.

“I think it was just my grandmother’s commitment that she had to preserving the playground that I had at her home. A place where I could read whatever I wanted to, where I could be curious, where I could play with a lot of the fabrics that she used when she sewed my clothes and my doll’s clothes. She had a fierce commitment to that. And I remember she used to say, when she would explain how other folks may not understand the way that we see the world or the standards that we had, ‘we’re a peculiar people.’”

When she decided to diverge from her training and professional practice as an aeronautics and astronautics physicist to explore a multidisciplinary artistic vocation, her family celebrated rather than shamed her. For Breon, the core questions propelling her practice remained unchanged. Like iconic polyglot Barbara Chase-Riboud, who recontextualized her training as an architect to master sculpture with metal, Breon is guided by physics, which supports the precision and exacting concepts that recur in her visionary métier. Both speculative and data-driven, Breon’s performances, installations and short films interrogate what systems are by pinpointing, with urgent analysis, how they inform our world.

In one short film staged as a public service announcement, Breon reviews the word “nude,” historically assumed to be a neutral color designation.

“Until 2015, the Merriam-Webster dictionary defined ‘nude’ as having the color of a white person’s skin,” Breon says. “Finding bras stockings and tights that actually match brown skin has been unnecessarily difficult for centuries.”

She continues by detailing the history and impact of this disparity and concludes by highlighting the work of Nubian Skin founder Ade Hassan, who, by inventing a lingerie line with broader skin tone offerings, innovated systems to counter the industry’s history of negligence. Breon regularly shares many of these films with over 22,000 Instagram followers. The core message in all her work is clear—oppression does not proliferate by happenstance; oppression is sustained by very real, human-designed systems. There is a silver lining. All systems can be resolved or retired towards the development of ones that are restorative, generative and protective of human rights.

“The scientific method is probably the framework that I use when I’m really trying to understand something, and I also have this habit of when I’m curious about something and then just become almost obsessed with understanding the different parts of it,” Breon continues. “I also almost always invite other folks in to be able to learn as well, and then participate in the interrogation, which is why call and response is such a big part of my work with inviting folks into the learning, but then also I usually start with some question that folks are invited to answer anonymously.

“It’s so important for me to try to understand whatever the existing system is that doesn’t serve a purpose. That doesn’t allow most people to benefit from existing within the system; it’s important for me to understand that so that I can imagine and construct whatever new system can make what existed obsolete.”

Breon’s approach empowers us all to realize that nothing that asserts itself as powerful can be unless we, too, give it that authority. That is to say, we don’t have to settle for a reality that oppresses us. Neither do we have to live within a paradigm that estranges us from our constitutional and human rights. By recalibrating our collective consciousness and retuning our imaginations, we can raise our self-awareness. Breon’s performances pinpoint pathways to rupture the ailing systems that shame us for wanting to evolve. She hopes her work is “developing the language and aesthetic” that supports healing movements.

“Abolition within this scenario is so important,” she says. “Multiple thinkers, writers, artists, and artists of different mediums can contribute to the development of the aesthetic. Performance is one of the languages that I use because it’s natural for me. It excites me, and it’s where I get to have the agency of infusing history with opportunities for action and aesthetic.”