About a block West of Eighth Ave and West 22nd St, Adrienne Elise Tarver’s fourth solo exhibit, Where The Waters Go, is nested in Dinner Gallery. The unassuming gallery is charming for how it juxtaposes the city’s noise and the gallery’s still tranquility. The setting fits Where The Waters Go as the exhibit calls on the duality between dream and reality in the context of white privilege and begs Black audiences to consider if their dreams rest in the idea of their physical destruction.

The exhibit will remain on view until June 29, 2024. Through dreams, Tarver’s series calls on historical and popular film archetypes to explore the complexity of Black female identities. By centering on the domestic, public, and private aspirations of Black women’s personas, Tarver explores how agency and visibility overlap.

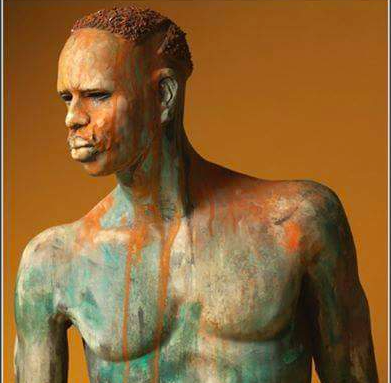

Untitled (Lounger) 2023, Oil on Canvas, 36 x 25.75 in

“Her practice is very much like an onion, where there are just so many layers within it,” Dinner Gallery’s Managing Partner, Celine Mo, said. “Then when you dive deeper, there’s just like so much meaning. It can be visually amazing but also really conceptually interesting.”

When shadows dance on dark walls, 2024 Oil on Canvas, 49.5 x 37.5 in

Her world-building is special because she doesn’t create women in her pieces, she creates worlds where Black women are in peace. When shadows dance on dark walls (2024) best shows this by centering a Black woman, naked and sleeping alone in her home. The curtains framing the foreground challenges the audience look and perceive her as a representation of Black women’s aspiratonal intimate, personal safety rather than an object of desire.

Unnaturally vivid colors from the background and middle ground bounce off each other in light layers of oil paint. Her paintings’ auras are surreal and striking visual tension between mellow and brazen.

Tarver’s work always starts with research. She approaches multimedia like books, films, and essays to draw deep social and psychological meaning from Black thinkers. Film archetype tie-ins reference Charlene Regester’s “African American Actresses: The Struggle for Visibility, 1900-1960”.

Where The Waters Go nods to historical Black actresses like Dorothy Dandridge in Carmen Jones and Eartha Kitt in New Faces. The life struggles of these Hollywood greats signify the push and pull reality of being a Black person in the public eye. Even with the material resources to self-define and cultivate safety by vulnerable visibility, that visibility puts them in danger of a destrcuctive stereotypes that want to force their identity into another person’s definition to disempower them.

The duality of pushing and pulling, visibility and invisibility, agency and disempowerment helped Tarer create the character, Vera Otis, who’s the central figure in the exhibit.

“There are certain archetypes that black women have been portrayed as or sort of spaces to fit within largely coming from media,” Tarver said. “The world has expectations for the black woman and the tropical seductress is a super reoccurring one. It came from this idea within the West of the exotic other, and the presentation of over sexuality and inability to control oneself.”

In the pieces A Place in the Sun, Lounger, and Untitled (pool umbrella lounger). Tarver’s character, the professional actress, Vera Otis is positioned idly — modeled in buff or a royal blue swimsuit — but not passively. Despite the model’s frivolity, Tarver’s composition brings a sense of being that shapes activity and passivity between diptychs and among Otis’s gestures.

A Place in the Sun (2024), Oil on Canvas, 61.5 x 85.25 in

She’s made active in the series by reflecting the audience’s gaze and she embodies a reality for Black women: found safety in luxury and solitude both while claiming agency in stillness.

When you see Otis, in Lounger and Held Gaze, she’ll hold a gaze if only to acknowledge you, but never to perform by smiling or posing. Tarver references Harvey Young’s book, “Embodying The Black Experience,” to develop her ideas around the luxury of being still in Black performativity. By being still, Otis stands in a freedom to not act for other people, because she’s steadfast in her comfort.

“Stillness is aspirational, a luxury,” Tarver said. “She (Otis) is caught in her private space. People are seeking them out to cater them. The privacy is fragile with stillness.”

Juxtaposed against Otis, the backgrounds of Tarver’s diptychs are hazy, dreamlike settings inspired by the Tarver Plantation — a real plantation that’s part of her family lineage in Georgia.

Thresholds (2024), Oil on canvas, 36 x 73.75 in

The Tarver Plantation is also the subject of her 2021 piece, Namesake. In A Place In the Sun, the plantation establishes a white gaze blindly staring into endless, lush opportunities. Namesake, establishes an oppositional gaze that yearns for the plantation’s dismantling at its threshold.

A Place In the Sun is painted softly, idyllic and mirage-like, although to show a privileged view from inside the Tarver plantation. It asks, who gets the view from inside the house? Inside the plantation, the white gaze sees a hazy open field, bright with round foliage as far as the eye can see. Outside, in Namesake, the night-coded vignette frames the plantation ablaze, crumbling, and haughtily glowing to represent a Black gaze at white supremacy.

Namesake (2021), Oil on canvas

Pieces without Vera are landscapes and slightly encourage projection. Without human subjects, the landscapes invite considering how it’d be to experience the space. The opposite happens whenever Vera is in the frame. She’s looking at you and the world she inhabits is hers alone.

The landscape slides in Tarver’s diptychs speak to passivity or dreaming “in-concept” because they’re quietly reserved and receptive to projections. Duality is loud in her works. The active pieces tell you you’re not there; the dream isn’t yours; you’re the outsider. The passive pieces want you to dream of being there. Either way, you’re outside looking in.

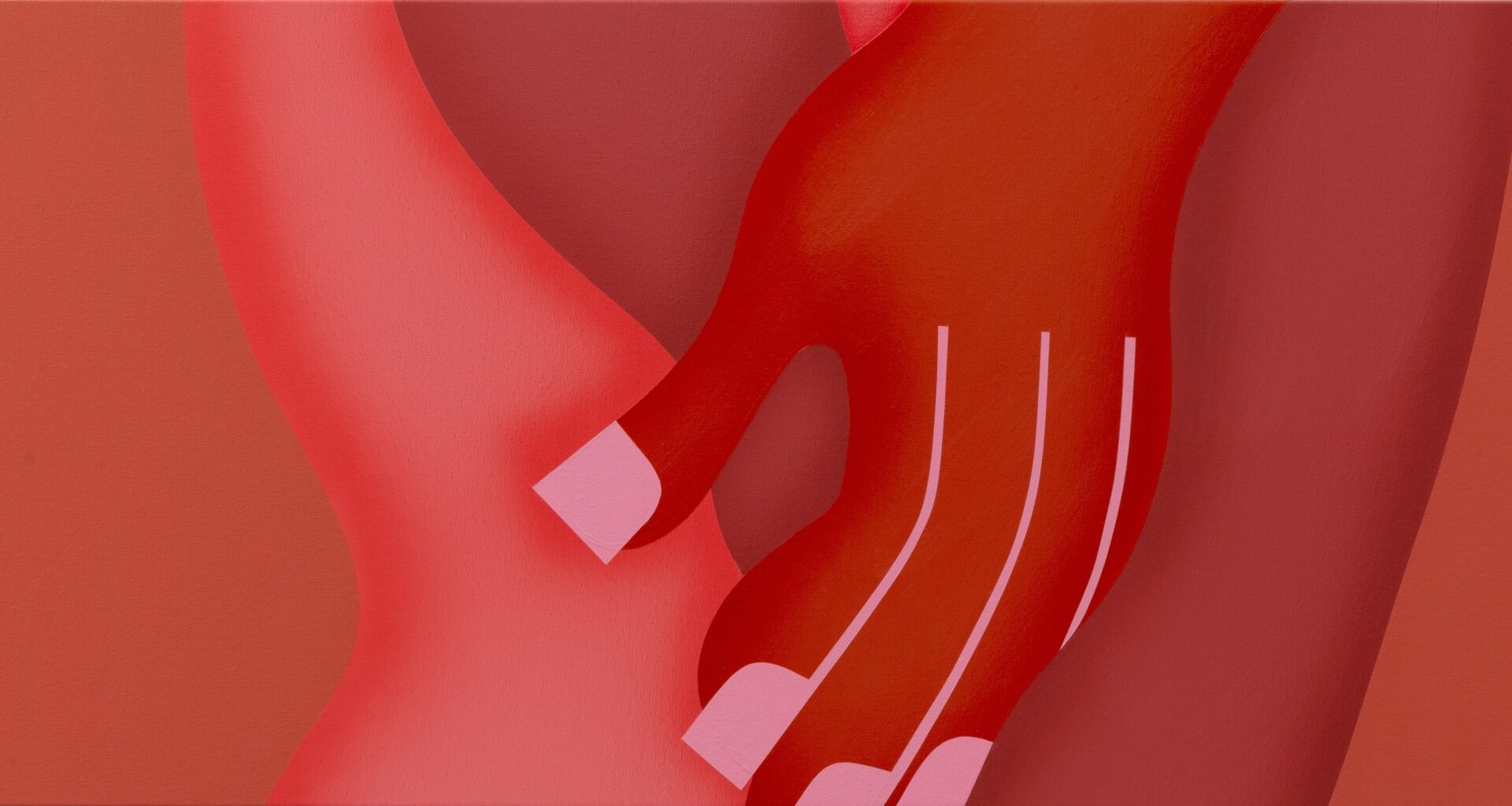

Disappearing bodies in the diptychs evoke juxtaposing activity and passivity by emphasizing public and private visibility. By making this distinction in her work, Tarver commands the audience to be present by calling on the active and passive all at once. It’s another layer of tension that makes her work provocative.

“What’s definitely intentionally put in the work is the calm, I want the desire to go in and and also to push back,” Tarver said. “Ultimately, the goal from the beginning is to add nuance to Black femininity. There’s a positivity and empowerment, but also a sadness and anger that underlies recognizing that you are a part of all these others’ perceptions regardless of what you think are.”

A Place in The Sun is under-painted with yellow but the red-tinted purple shadows and cool greens leap into the frame to make a tense and mysterious mood. Her use of color visually represents the turmoil of visibility, because being seen as vulnerable can be dangerous and uncomfortable.

Tarver makes Otis’ gestures purposely ambiguous as a form of protection. The desire to live in a passive space comes from self-preservation for the elevation of rest. Her distant stares show how she’s attached to a dream, an idea, that may not persist, therefore space helps her claim agency.

Through this series, Tarver invites conversation about American dream homes. Spacious, private, and lofty dream homes built call back to plantations and Black exploitation through chattel slavery. Among all of the intentions with duality and tension, what underscores Where the Waters Go is how, without personal agency and presence, aspiring to luxury and American success are accessible to marginalized people.