By Willie J. Wright

On July 23, 2020, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) unveiled Nathaniel Donnett’s Acknowledgement: The Historic Polyrhythmic of Being. The installment was the latest in a series of collaborative performances by Donnett that interrogate the lived experiences of Black residents of Houston’s historically Black neighborhoods-the Third Ward (da Tré), the Fifth Ward (da Nickel), and the Fourth Ward (Freedmen’s Town).

In doing so, he adds himself to a list of respected visual artists and performers for whom these neighborhoods have been a muse (e.g., John Biggers, Rick Lowe, Lovie Olivia, Robert Pruitt, Autumn Knight). As with his previous works, Donnett presents the artistic merits of Black neighborhood life to audiences within and beyond these communities, and as a result, elevates the spatial practices and theoretical contributions of those he deems “Houston’s top sculptors.”

In a 2014 performance entitled, In the Memory Of…, Donnett inverted the internal machinations of Black life. Through a premature staging of his own funeral, a result of state-sanctioned violence via the Houston Police Department, Donnett illustrated the precariousness of Black life, all the while echoing the movement for Black lives.

Throughout this performance, Donnett remains present yet unseen as his “body” lingers in an open casket with more cheap caskets around it. Meanwhile, mourners (e.g. family, friends, and patrons of the arts) became participants of a Black Baptist homegoing service set within the CAMH. As Donnett lies in state, those in attendance (and those watching online) are brought into a Sunday service through the gravel-inflected tenor of a Southern preacher, who himself is a performer in this project.

Months prior, he who was preacher invoked the Texas Gulf Coast region’s Black cowboy culture as a participant in The Black Guys’ 24 hours public performance at an area bus stop. (See the essay, No Blank Canvas: Public Art and Gentrification in Houston’s Third Ward, for an analysis of this performance.) By countering the gratuitous violence that saturates Black social life with a commonplace Black cultural practice, Donnett displayed what Jared Sexton referred to as “the social life of social death.”

Furthermore, Donnett’s affinity for relational Black experiences and his native Third Ward illustrate that the practice of everyday Black social life may do for art what Katherine McKittrick, in a lecture presented before the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture, suggests art does for theory; that is, it elucidates that which the latter cannot. (In an interview about abolitionism with Mariame Kaba, Ruth Wilson Gilmore also addressed ability of art, as an analytical defined practice, to inform Black political thought and organizing.)

The longstanding presence of Black communities in Houston is the impetus for performances, installations, and critiques that ground Acknowledgement. As a history of the present, it narrates Black Houstonians’ memoirs during a time when Houston’s historically Black neighborhoods are being transformed at a rapid pace, dislocating working-class Black residents and the cultures they create.

Thus, it was not lost upon the viewer that the green banner that helped comprise Donnett’s installation was draped upon a strip of construction fencing that shrouded the renovations to the CAMH’s exterior. Following the unveiling of this installation, I spoke with Donnett about his practice, and how the city of Houston-and whether the movement for Black lives-influences his art.

______________________________________________________________________________

WJW: Please explain the concept for your most recent installation, Acknowledgement: The Historic Polyrhythm of Being.

ND: It is a component of a larger project titled Acknowledgement. This project is an imagined thought experiment. It’s a proposition set up to think about or support the art-is-life argument or philosophy. I wanted to think about how one could prove this idea through process (making and time) and space (locations and engagement). I’m also thinking about text upholding plurality in meaning and cutting across time and space.

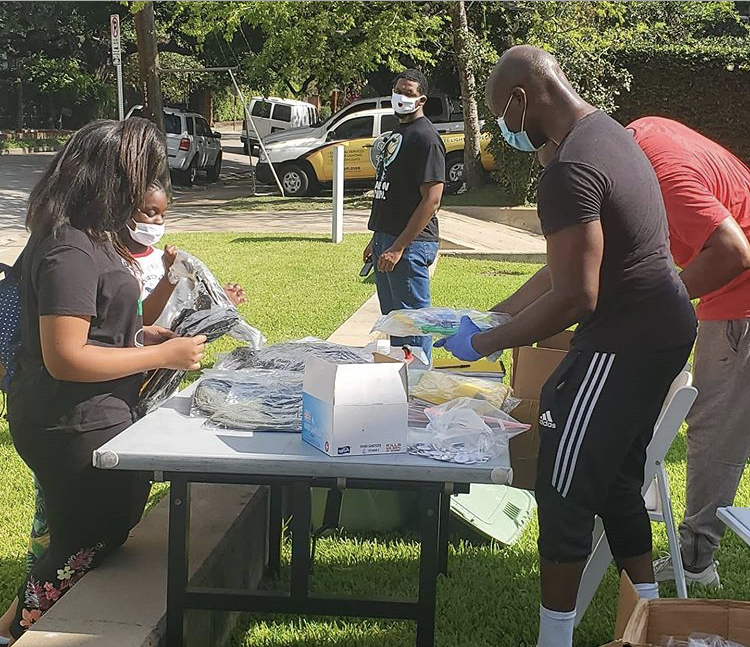

I coupled that with the ongoing social transformations (forced and voluntary) of three historically Black neighborhoods in Houston-the Third, Fourth and Fifth Wards. That was the art-and-life aspect of the piece. What formulated were ideas on memory, language and history. To gather materials for the installation, I sent out an invitation through social media to friends and whomever would listen, to find students from these areas to donate a backpack in exchange for a new one which could be used for school, video games, or whatever.

It’s a community-based project that engages the community in terms of exchange and value. However, it’s also an exploration of form, accumulation, installation collage, Southern quilting, abstract painting, sculpture, sound, light, graphic design and the makeshift. This, for me, is synthesized into what reads as a social aesthetic of the everyday. But I never really know where things are going until I get there or get close enough to say, “I’m good with this at the moment.”

WJW: Who funded the work, and how did you come to collaborate with the CAMH?

ND: The CAMH funded it as a commission, but Yale University funded it for research in the form of two grants-the 2020 Dean’s Critical Practice Research Grant and a 2020 Art and Social Justice Initiative Grant. The people and organizations who participated in the exchange funded it in terms of social capital. The CAMH is undergoing new construction on its exterior and interior spaces. They also have new staff, which was something I didn’t know about at the time. It was sheer coincidence that Hesse McGraw, the CAMH’s director, asked me if I was interested in creating an installation/partnering. The proposal lined up with my bigger project concerning public art and community engagement. So, I told him, “Yes, I’m interested.”

WJW: I am interested in your use of children’s backpacks, which remind me of the back-to-school drives that take place in communities at the end of each summer. Why include children’s backpacks into your installation?

ND: The ideas come from different directions and my desire to create an ensemble. Bags and the youth have been a consistent go-to within my practice. Paper bags, trash bags, zip lock bags, etc. I’ve also incorporated kids as subjects and as psychological and sociological points of departure. In one instance, backpacks on the fence indicate pharmaceutical activity happenings. In another sense, it gestures to a quote by James Baldwin where he says, “We carry our history with us.” The backpacks light up at night and blink, in morse code, an excerpt from James Baldwin’s Uses of the Blues, a verse from Solange’s song, Mad, and the words, “A Love Supreme,” referencing John Coltrane’s song Acknowledgement.

Lastly, timing. I wanted to finish this commission before the summer. Knowing school begins in the fall, I knew there would be a need for backpacks in these neighborhoods and that new backpacks would be helpful to parents financially-particularly, because of COVID-19.

WJW: If watched from afar during the daylight hours, Acknowledgement appeared to be simply a string of backpacks. However, seen up close, one notices photocopied images inside the clear backpacks. Who were some of the faces in the backpacks, and what was their significance to Houston and the installation?

ND: Some of the faces are Texas Senator Barbara Jordan, who is from Fifth Ward, Texas, and Congressman Mickey Leland, who is also from Fifth Ward. Both went to Texas Southern University (TSU) which is located in Third Ward. The Reverend Jack Yates became a freedman after emancipation and a preacher at Antioch Baptist Church in Fourth Ward. A high school was named after him which is located in Third Ward (Jack Yates High School).

This shows how space and time can collapse and how locations and people overlap. This type of historical engagement has indirectly shaped some of Houston’s aesthetics for Black artists. I wanted to celebrate and acknowledge this fact but not sentimentalize the areas they helped establish and/or leave footprints upon. The backpacks speak to other issues that require redress, but are often individualized and recognized as systemic and structural-such as poverty, educational disparities, gentrification and displacement. These snapshots, along with other archived photos and photos I’ve taken, are memory fragments encapsulated within the backpacks-as-memory capsules.

WJW: What is the meaning of the word that hung next to the backpacks: PSYCHOSLABACKNOWLEDGMAYNEHOLUPBLACKSPATIALISTIC?

ND: It means whatever the viewer wants it to mean. But it is something where you use your imagination and create meaning or create space for meaning. I was also thinking of words that would be recognized as slang and phrasing familiar from the neighborhoods that are the subject of the project. They form along the thinking of making up words to make up new words. They are conceptually linked to music and film.

The music group, Parliament and Funkadelic, uses the word “Psychoalphadiscobetabioaquadoloop” in a song (Aqua Boogie). Outkast named their album Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik. Issac Hayes has a song titled, Hyperbolisticsyllabicsquedalymistic. Filmmaker William Greaves titled his film, “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm.” Then, there’s “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” which was also a song.

Overall, this word is about experimentation, play, creating space and engaging in Blackness that’s obvious in times like these. Then there’s the question of value. I think formal language and informal language have value, yet it’s not viewed that equally. I think I’m playing around with that and ideas of image and text recognition.

WJW: Why did you decide to embolden it on a construction fence outside of the CAMH?

ND: The fence was used as a way to prevent the public from entering the construction site. They initially wanted something on a banner, but I wanted to think about public and private in a different way.

WJW: During one of your backpack/school supply giveaways for Acknowledgement, you missed an opportunity to capture a sound recording of a brother-who happens to be one of the Third Ward’s shade-tree mechanics-blaring music as he rode by in an older model, black Mercedes. Why were you interested in his soundscape?

ND: Part of this overall project, Acknowledgement, has a sound component to it. I recorded the everyday sounds of the Third, Fourth and Fifth Wards as a way to engage in visibility and disembodiment. Music is a big part of my practice, and this project is about sound, so I wanted to catch him rolling by, but you all were talking too loud. LOL. But seriously, my thoughts were how these different sounds can become something interesting as a collective and a disruption. The collective has power and so does a collective of people pulling together for a common goal.

WJW: Was it the volume?

ND: It was the volume and the presence, and how it interacted and contributed to what was already happening at the time.

WJW: Does the soundscape of Third Ward have a particular resonance, similar to that of the spaces and place-makers within the neighborhood?

ND: Yes. I think it is all of that. It becomes a reminder how no one is an island, and yet we all contribute to our situation whether it is implicit or explicit, generative or limiting, or somewhere in between. It is most likely in between.

WJW: In your expressions of Blackness across your performances, I sense there are commentaries on the class dynamics of Black social life.

ND: Yes. My works on Black social life, as a default, come out of working-class sensibilities.

WJW: I also notice a thematic sense of loss and belonging. What would you say is the role of these dynamics in your art?

ND: I’m not sure about belonging more so than relating and connectivity with each other, alienation, and forms of refusal. Maybe that’s a facet of belonging but it can also become non-critical of a thing, space, idea, or person. It can fall into sentimentality and become overly romanticized.

Definitely loss. Loss shows up in forms of death and a type of abstraction that could also be a type of fugitivity or migration from a thing. But still holding onto a thing. I think life is that way. This idea of moving (not even thinking linearly) and dropping something off and picking something up. Our very being is an accumulation of exchanges where we give and take. Loss can come out that way. These things, as a dynamic, render and help push the practice into incompleteness and uncertainty. This allows for space to exist, and simultaneously, to create and imagine.

WJW: In previous works, you invoke the term, “Dark Imaginarence.” What is Dark Imaginarence and how did you come to create this theory-or is it praxis-of Blackness?

ND: Dark Imaginarence is a lived experience from childhood experiences and creating imagined spaces for myself. Also, I noticed how Black music gets co-opted and consumed as something other than what it was and repackaged into something else. It’s a way to self-identify my practice. Dark Imaginarence is slightly poetical, statement, manifesto, and collaged. But yes, a praxis of Blackness is a way to put it.

I initially thought about Houston’s Black aesthetic as a thing. I started to think about my own practice, and how I didn’t want it to solely rely on being a product or simply an object created for consumption or even collection. It’s not really about artwork in the singular. It’s about Blackness, art and the everyday. A social aesthetic that engages within the world, spirit and ideas.

It’s also about process, collaboration, community, and the relationship to our socio-political and cultural realities. It’s an engagement with all of these things and understanding that, as a practice, it is not fixated and remains in flux, incomplete and non-linear. That is not to say it is about anything and everything, but it could be. To streamline it, it comes out of sayings like, “I can show you better than I can tell ya.”

WJW: And how does it relate to what you referred to, in a talk at Wichita State University’s Ulrich Museum of Art, as “social art deconstruction?”

ND: Yikes! I don’t remember that talk. I’m probably thinking about nuance in between spaces. Those spaces are not as obvious to see, and therefore, they have to be pulled apart. And I think one way to do that is through deconstruction or a break-down analysis of the experiences when engaging with our social imaginaries and spatiality. In other words, thinking of an action of deconstruction as a practice or aesthetic critique within itself.

There is also a lot of critique to be had when it comes to those things. Exploitation and clout-chasing, for example. Also, it relates to art’s limitations and its origins in Europe and the West’s idea of art as opposed to different views of it globally. What is the “other” or the marginalized view in terms of who participates and who has participated? What has been stolen or borrowed but not credited for their contributions? Is the term art, as we know it, dated? I don’t know. Just some things that I think about.

WJW: There seems to be an irresistible interchange between contemporary Black art(ists) and Black humanities scholars (e.g., Fred Moten, Katherine McKittrick, Frank Wilderson, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, etc.). What do you see as the basis for this relationship?

ND: I think at this point, it is just time that people begin to see Blackness in its multiple forms. I think the very thing that connects them all, in my opinion, is multiplicity, adaptation, improvisation and humanity. The question then becomes, how can these ideas be stretched, arranged and redefined? There are no limits. I also think these theories become another form of collaboration.

WJW: Speaking of scholarship, which theorists have informed your work and theorizing?

ND: In terms of the contemporary, Fred Moten, Andrea Roberts, Paul C. Taylor, Mandoki Katya and Yurika Saito. I’m looking into learning more about Saidiya Hartman and Denise Ferreira da Silva. I also look at musicians such as D’Angelo, Solange, Jason Moran, Chris Dave and Robert Glasper. Arthur Jafa’s Black Visual Intonation idea is very interesting as well.

Also, just everyday people. Like the cat in the neighborhood who places a TV screen on the back of his bike and has rigged it to show TV shows and videos as he rides around town. Family and friends are theorists. The guy who barbecues in the parking lot of clubs and small businesses. That’s part of Dark Imaginarence, locating theory within our everyday spaces. I don’t limit theorizing to what one would consider traditional theorists in academia.

WJW: In the performance, In The Memory Of…, you staged your own funeral. What struck me about this performance is that it felt more like a Southern-style funeral than a performance. I felt as if I were in the Third Ward, Fifth Ward, or any ward, and not inside the CAMH. I noticed your wife was sitting in the front row, that the “pastor” walked up and whispered consoling words in her ear, the call and response, and the viewing of the body. What was that experience like for you as an artist and as a Black man?

ND: The experience as an artist was very real. If you’re sensitive and vulnerable enough, you can really access your own mortality-and sense of self-when lying in a closed casket. Many have had this experience before. It is specific. It was meant to be like a Southern funeral. I believe that more aesthetics have come from the church (regardless if you practice the religion or not) for Black people besides music, language and fashion aesthetic.

I tried to engage in that, and what people felt was what people felt. As a Black man, my family and I have had the police kick in our door with guns pointed and handcuff us, all as a result of mistaken identity. I mean, about 10 SWAT folks inside the house, five in the back of the house, five in the front, and the blocks were sealed off. I think many Black people have experienced racial profiling or know folks who have been racially profiled.

WJW: Expanding upon this performance, I noticed a number of local artists and Third Ward residents attended this performance-as audience and performers. I am thinking in particular of the “pastor” and the “pallbearers.” It made me wonder about the role of not just the Third Ward as a place that influences your art, but as a community of place-makers who are present in your performances.

ND: Right. I mean it is a community. I’m reliving my childhood amongst people who were not a part of it but wish they were. I’m really into collaborations. Everyone has a voice and is valuable and it’s interesting to see how something could materialize from different points of view.

WJW: You were in Houston when George Floyd was murdered by the Minneapolis Police Department. As someone who was raised in the Third Ward, Floyd’s neighborhood, what went through you when you learned of his murder? And did you channel your thoughts and feelings into art?

ND: What went through my mind was rage, anger, sadness, and thinking this is not going to stop. At this point, I am not surprised when I see it. I’m only saddened deeper by it, and hope that I don’t experience it. I am looking for real justice to come around, but it’s always late if it ever arrives. I think about the circumstances these systems play in our daily lives, and how they can limit our growth and development as human beings.

That is not to say, people aren’t hopeful or don’t try, but at some point, it wears you down. I felt all sick when I saw it. I never finished looking at the entire thing, because I know how death looks, and I also know what evil looks like. So, there was no need for me to see much more. I did channel it. I created a collaged, duct-tape piece that showed Floyd with his daughter and friends. I placed it on the fence of Jack Yates High School (where I also attended) as a public memorial. I wanted it to be present and not be present, so it was modest in scale and more intimate than a mural would be.

WJW: You’re currently studying for an MFA at Yale University. What are you learning from and imparting upon this intellectual arts community?

ND: I’m learning a lot and reading more theory than before. There’s plenty of room to take risks as an artist, and mess up and develop. The course selection is great too. Yale is interesting. I realize that even at Yale, the art department is not treated like Yale’s law department. That was the same M.O. at TSU. I guess it’s a snapshot of the greater society we live in and how art is valued-or not. I’m pretty cool with faculty, cohorts and fellow colleagues. They’re pretty supportive and informed. At first, I didn’t know what I could bring to that space, but you realize, or you’re reminded, that everyone has something to offer.

On the flip side, I still experience micro-aggressions with people while walking on campus or in the neighborhood. Some folks still cross the street when I walk on the sidewalk. Sometimes you can feel their energy stop and pause because of my presence. Some people still assume I’m aggressive, etc. Those things aren’t changing (in my mind) because this is America. However, I’m honored to have an opportunity to get an education from such an institution and to develop my practice.

WJW: You were recently on a virtual panel entitled, “Black Art in Houston,” for The Museum of Fine Arts Houston. During that session, an audience member posed a question regarding how gentrification and urban renewal will impact the future of Black arts and artists. This question was in response to the panelists discussing the significance of the Third Ward, as a historically Black and working-class community, on Black arts in Houston. I am curious how you view the subject matter of your performances and installations (e.g., reused backpacks, morse code, a staged funeral) in relation to this question and the future of Black arts and Black residents in Houston.

ND: I view my practice as a bunch of questions and a pair of glasses. What comes to mind is the 70’s show, Sanford and Son. When Fred [Sanford] needed to read something, he would look into a drawer that was full of glasses. They all were different. He’d search until he found the ones that worked and allowed him to see clearly. I’m trying to fully understand things myself through my practice but also open up discussions about spaces and ideas that I see that aren’t easily visible.

The funeral, for example, wasn’t about death full-stop. It was about moments between life and death, what creates them, and ritual. I’m a small part of a bigger picture. I think the future of Black artists is dependent on risk-taking, experimentation, collaborations, conversations, understanding, self-reflection and critiques. I think when you collaborate with people outside of the arts, like activists, educators, scholars, scientists and musicians, you begin to get some things done.

We shouldn’t make the mistake and think art is only ornamental or limited to design. We can keep ideas that work and that are meaningful, but we can also push past old ones and create a cycle of push and pull that embraces the whole, not just the individual.