In late June, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Florida, ACLU of Florida Greater Miami Chapter and Valiente, Carollo & McElligott, PLLC filed a lawsuit against the City of Miami Beach for violating the First Amendment rights of Jared McGriff, Octavia Yearwood and Rodney Jackson. The lawsuit comes in the midst of a nationwide conversation on Black representation and voices.

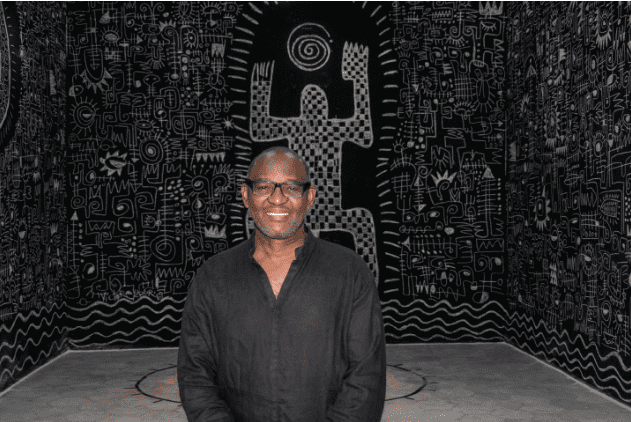

“The timing wasn’t strategic, it was synergy, really,” said Jackson, the artist whose work was forcibly removed from Memorial Day Celebrations in Miami Beach. The painting, entitled Memorial to Raymond Herisse, was a tribute to Raymond Herisse, a 22-year-old Haitian American who was killed by the Miami Beach police during Memorial Day Weekend in 2011.

Since the early 2000s, every Memorial Day weekend, thousands of Black tourists and locals gather on Miami Beach for “Urban Beach Weekend.” Unlike December’s Art Basel Miami, Urban Beach Week has never been sponsored by the local government. Urban Beach Week, described as a hip hop festival, brings in between 250,000 to 300,000 people compared to Art Basel Miami Beach’s 80,000.

The event-turned-festival made national news in 2011 when Miami Beach police fired 116 shots at Raymond Herisse, fatally wounding him and injuring four others. In 2015, prosecutors at the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s office declined to charge the officers, and a year later, the city settled with Herisse’s mother for $87,000.

In 2019, Miami Beach announced “ReFrame: A Memorial Day Filled with Arts & Culture on South Beach.” According to the city’s website, visitors were invited to come to Miami Beach for events that would reimagine Memorial Day Weekend on Miami Beach and “spark crucial conversations about inclusion, surveillance and propaganda, using the works of local artists, curators and organizers.”

In between the early Urban Beach weekend’s early aughts and the latter events in 2019, Miami and Miami Beach themselves had changed. Miami became known as a city of the arts. Introducing a city-sponsored arts initiative to Urban Beach seemed to align with the idea of Miami Beach as an arts destination. However, within two days of the show’s opening, the curators were informed that the city required they take down Rodney Jackson’s painting memorializing Herisse. They were told that the Miami Beach Police Department objected to the work, and their options were to either take the piece down or deinstall the exhibition entitled, I See You, Too.

According to Co-Curator Jared McGriff, the goal of the exhibition was to “convey a sense of the community policing the police, where the community watched the police and listened to police scanners,” going from the surveilled to the surveillants. The exhibition also focused on the racial history of Miami Beach from segregation to modern-day police brutality and militarization.

After the city officials demandedRodney Jackson’s work be taken down, the curators agreed “under duress,” and it is this push that ACLU Attorney Alan Levine asserts violated their First Amendment rights.

Levine, a civil rights lawyer for the past 60 years, joined the case because he sees this as a clear violation of the First Amendment.

“The city treats this as if it were their private money, and [because] they didn’t like this art, they don’t have to pay for it. But of course, it’s not private money… and the government doesn’t have the right to only fund art whose viewpoint it agrees with,” said Levine. “The government doesn’t have that prerogative under the Constitution.”

Yearwood, McGriff and Jackson are also suing for reputational harm as a result of fallout from the experience. Due to some court hearings being pushed back because of Coronavirus, Levine says they had considered pushing the lawsuit back to another time, but after protests following the death of George Floyd, the case seemed more relevant “than ever.”

“Black people, especially on Miami Beach, our First Amendment rights and Fourth Amendment rights are violated all the time, and it’s rare when it’s actually on record, and in this case, it was on record. So now it’s time to do something about it,” said McGriff.

Throughout this moment, we are seeing a constant outpouring of #BlackLivesMatter posts from museums, corporations, organizations and “allies.” Large institutions have put forward statements of support and allyship, only to be called out later by Black people and other People of Color who work and/or have worked for them. Organizations and institutions are being criticized for wanting credit for being progressive without having to actually make substantive changes.

It also speaks to how often the push for diversity and Black representation is surface deep—especially when meaningful critique is engaged. Do these spaces want the opinions and the thoughts of Black artists who don’t agree with them? What does it mean for the state to sponsor a conversation about state-sanctioned violence?

Last week, the New York Times published the aptly titled article, “A Rush to Use Black Art Leaves The Artists Feeling Used.” Black artists spoke about the present moment and the feeling of tokenism. As we see budget cuts to museums and nonprofits affect their “POC outreach” programs first, it becomes clear that to some institutions, Black artists are and were a fad.

As the current moment intensifies with Black Lives Matter protests now reaching a two-month mark, it should be a matter of course that the fight for First Amendment rights should be one of the focal points amongst the Black arts community. Yet, the mainstream conversation about censorship has frequently centered around white artists. In instances where white artists are called out for racism and/or cultural appropriation, conversations harken back to the “slippery slope” of government censorship.

However, when Black artists and curators are censored by Miami Beach, equal progressive outrage is missing. The now infamous Dana Schutz Emmett Till painting, for example, was called out by many Black artists and scholars, including Hannah Black, in a public open letter calling for the piece to be removed from the privately owned Whitney Museum. Shortly after Black’s letter, Black and white artists en masse signed Coco Fusco’s letter warning of the “[slippery slope]” of free speech violations. Yet, when the city of Miami demands that work memorializing their victim of specific, state-sanctioned governmental violence, the larger art-censorship conversation isn’t as prominent.

Black artists and curators are honoring victims of state violence and using their platforms to create dialogue. And the question arises: when will their rights and work be free from policing? As we interrogate the institutions that uphold white supremacy, are we looking at the institutions that actively censor and decenter Black expression? Are we pushing this conversation as far as it needs to go? This lawsuit is indicative and pertinent to this moment we are in, and we should all be paying attention.