This October, the historic Tower Hotel in Little Havana will play host to a new set of guests when Juggerknot Theater Company premieres “Miami Motel Stories” in its lovingly restored halls and rooms. As the oldest boutique hotel in Little Havana, the Tower has borne witness to sweeping change since its doors first opened in 1920, and it’s this tapestry of experience and emotion which the production aims to bring to life.

Written by Miami playwright Juan C. Sanchez—and inspired by a previous play of his, “Paradise Hotel”—“Miami Motel Stories” delves into the lives of different people who stayed in the hotel since the 1950s. The director tasked with shepherding these rich stories to new audiences is Tamilla Woodard, a noted playwright, and director who is also one of the leading practitioners and proponents for immersive theatre, an experience which makes the audience as much a part of the story being told as the actors and the setting itself. For many audiences, the experience is a revelation, as it was for Woodard when she first experienced it. “It unlocked doors in my psyche and creative energy that was so useful and permissive,” said Woodard. “It said that the boundaries I’d been looking at just didn’t exist.”

As co-founder of PopUp Theatrics, a partnership creating site impacting theatrical events around the world and in collaboration with international theatre artists, Woodard has staged such productions around the country and the globe to appreciative audiences and much acclaim, now adding Miami to that impressive list. Sugarcane spoke to her about her career and her involvement with “Miami Motel Stories.”

Jason Fitzroy Jeffers (JFJ): Let’s start at the beginning: how did you fall in love with theater?

Tamilla Woodard (TW): It started as a kid, seeing school plays, that sort of thing. I grew up in Houston, Texas, and I went to see August Wilson’s “Fences” at The Alley Theatre in Houston, Texas, the main theatre there. I was ten maybe, so I didn’t understand everything that was going on, but there was a moment near the end of the play where death comes to get Troy, and he’s fending it off with bat—“come get me… Come get me!” I don’t know how exactly but the theater made the ghost come to him, and I remember thinking, “oh my gosh, they made magic!” I still say that in my rooms, that we’re making magic, which is using the tools around you to make people believe in things that are extraordinary and beautiful at the same time, a world that people want to believe in. That’s what I’ve been in pursuit of ever since then.

JFJ: How did you get into directing?

TW: I remember being an undergrad at Carnegie Mellon and I said to myself, all I want to do is make a living as an actor. When I finally started doing that, I said to myself, “this is just a regular job!” My feeling at the time was that I was on an assembly line and my job was to get in there and in 16 days be memorized and blocked and do this show in front of an audience. And I couldn’t figure out how to successfully access myself in a significant way. I just felt I had more tools than I was able to demonstrate in that particular environment and that I should find a different form of expression as a storyteller.

First I went to L.A., mainly because I was on the regional theater circuit and I just couldn’t spend another cold winter in theater housing or back home waiting for my next job in NYC. I drove my mom’s car across the country and almost as soon as I got to California, went to audition for the Yale School of Drama because they had The Cabaret. I just didn’t understand how one became a director, but I understood that if you got into The Yale School of Drama and could do this extracurricular thing called The Cabaret, they might let me direct and I could figure it out under the guise of an actor. I got in, and I immediately spent as much as time as I could at The Cabaret, eventually becoming the first person in the acting program to become the artistic director. They surrounded me with amazing people, and I found the job was the same as the director in any room, which is to inspire and facilitate people’s passions towards the same thing; you get people with immense talent and passion, and you just stoke the fire and ask them to deliver more and more until we arrive at something we’re proud of as a collective, the whole truth that is possible at that moment.

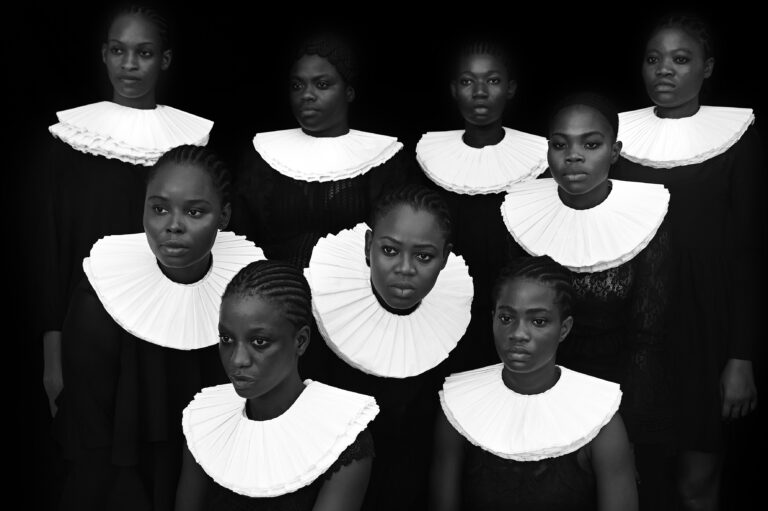

Above: Tamilla Woodard working with Dr. Paul George of HistoryMiami.

JFJ: Immersive theatre is a new concept for most people. How are general audiences taking to it?

TW: This has been a great year because the commercial theatre community is coming around to immersive work. “Natasha, Pierre and the Comet of 1812” was on Broadway, and “The Encounter” was on Broadway; there are a bunch of vehicles for storytelling that is unusual in their way of storytelling that was in very big, commercially successful ventures, which I think helped open up opportunities for the kind of work I do and for the people I like to work with. People have been reaching out to me to do larger scale events, and I’m so glad that there’s finally funding for this type of work so that people can realize it as artists and participate in it as part of an audience.

JFJ: You’ve been to Miami before, but this is your first real time in Little Havana. What fascinates you about the community?

TW: It’s such a microcosm of America. You go to Domino Park, and you have the little Korean ladies madly playing dominos with the older Cuban guys, and the young people marveling at their skills. The botanicas, the restaurant; there’s this sense of easy welcome in those few blocks that I love. Tourists and folks that aren’t tourists alike. It feels like a crossroads, a place of intersection where people are still curious about each other.

JFJ: What’s so compelling about this particular piece, and what made you want to be a part of it?

TW: Juan is amazing; he blows my mind. He takes care of these characters, paying such attention to what the story can be and what that space is offering. There’s just so much heart in his work.; Juan is a good structuralist which is very useful in site specific work because we’re dealing with so many unpredictable elements, be it the audience or car horns outside; you have to be able to be hooked back into the people in front of you in a very solid way.

Philosophically, what I think Juan’s concerned with is that history is important, yet it can be delivered in a way that’s sexy, luscious and wonderful, in a way that makes you feel excited about it. I think an audience should see this because we made it for them. And I mean that truly: If they’re not there, the show doesn’t happen, they’re in the middle of the thing.

It’s for two people at a time, a very intimate experience that says that who you are as a spectator is as important as what you are seeing. It isn’t a forced entertainment, but one that is the story that lives inside you. This work is about how you experience it; you can find yourself in it.