This year, Sugarcane Magazine is initiating a series of interviews with meaningful creatives. Artists, actors, DJ’s and the like that push buttons and create powerful cultural narratives. This week, we speak with conceptual artist Kameelah Rasheed. Known for her exhibits at MoCADA ( Museum of Contemporary African Diaspora Art), The Studio Museum in Harlem and most recently her presentation at The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. My conversation with Ms.Rasheed introduces her inspirations, family life and personal experience that make her a sought after artist.

Melissa Hunter Davis (MHD): The first question for you is, I noticed that your academic background is in education and social sciences. What inspired you to alter your trajectory into visual arts?

Kahmeelah Rasheed(KR): I did a lot of art as a kid, but there wasn’t really a clear career path for it. It was just something that I liked to do. After I started college, I was like, oh, I like public policy, and I really like education, and that seems to be a clear path, so that’s what I did. It’s something that I was passionate about, but there was something clear and direct about it, whereas for art, coming from a poorer background, it’s a little bit harder to have a conversation and say, “I’m going to be an artist,” and not really have a clear idea about how that generates income. I always had art in the background, something I always thought about constantly.

I moved to New York, in 2010 to take a different teaching position. When I moved here, I was still making art, but it was definitely more of a hobby, something I did. Sometimes I would enter shows, but a lot of it was just me having fun. Then I started doing a lot more of it and realized it was something that caught on for me, but also something that felt that I could grow into and I could find some type of pathway to do something with. I started thinking about how my background in public policy, and how my background in education could impact and make. I’m thinking about how that, my academic background, could impact to the direction of my work. A lot of my work starts in research; and from that research, whether it’s just me sitting on the train and looking at people, or looking at a book and doing more direct, traditional research, all of it starts with research and then from there something visual comes out of it.

MHD: Okay.

KR: I don’t think that my trajectory actually changed. I think that over time, what medium makes the most sense for me to articulate myself has just changed over time. I feel like I was doing a lot of work in education and public policy that articulated what I wanted to articulate at a particular point in my life. But I think as I got older I thought about art as another medium, so to speak, to sort of express those ideas.

MHD: I was reading some past interviews about your home life, and about your father. He didn’t allow you to watch television or radio, so I think you answered that question for me. Because I was going to ask, how did your family life influence the art that you practice now?

KR: I grew up with parents who lived through the civil rights movement, Black Power movement, went to college during this time. I feel like when they left college and started having a family, a lot of that was passed on to us. So my parents didn’t let us listen to music and watch TV, but the music we got to listen to was Stevie Wonder, and Bob Marley, and Gil Scott-Heron.

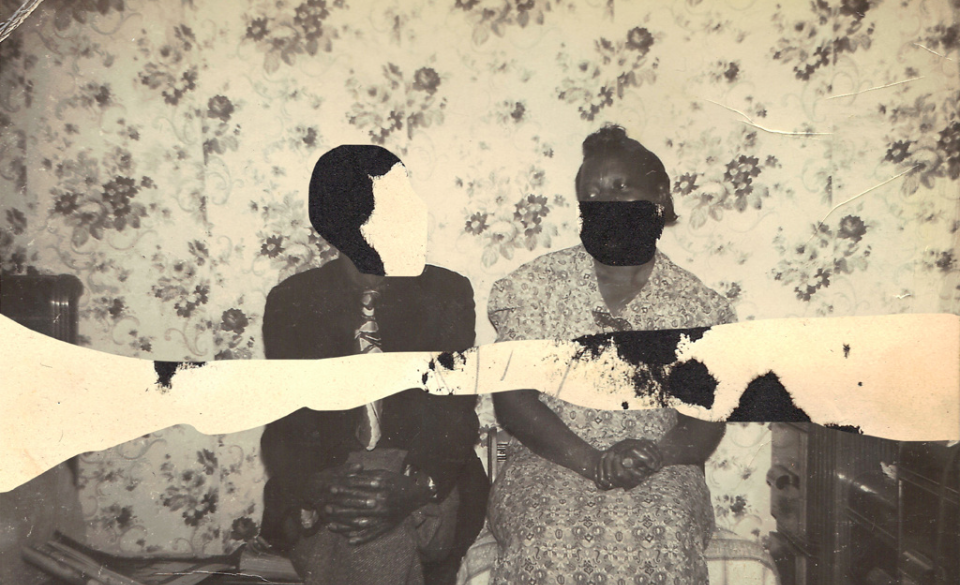

Flexin’ my Complexion by Kameelah Rasheed

MHD: Good stuff!

KR: When we were 9 and 10, and that’s all you hear, a lot of it subconsciously becomes part of who you are. Listening to Gil Scott-Heron, and listening to him talk about Johannesburg, and listening to him talk about the revolution not being televised, and being 9, and not knowing exactly what it is that he’s referring to, but knowing that there’s an emotional anger there that just feels natural – and there’s something that’s about me, about my blackness, that was embedded. What he was talking about it was really powerful to see it. As I got older and started to understand a lot of what my parents were doing, a lot of my artwork comes out of trying to reach back and make those things that were sort of implicit lessons to me more explicit for the people that I’m speaking to in my work. I think that Gil Scott-Heron, of course, is no longer with us, and I had the privilege of seeing him perform right before he passed away, in Marcus Garvey Park, and just having that moment to connect that childhood experience to my adult life was real important to me because it put all the pieces together and made more sense as to why my parents raised me in the way that they did. I think as a kid, you’re obviously annoyed when everyone else is talking about music videos that you’ve never seen, but I am really grateful that my parents sort of curated a particular type of upbringing for me that I think definitely influences how I create work, and for whom I create work, and also just my desire to constantly go back to my childhood as a place of inspiration.

MHD: As a child I was Muslim-

KR: Oh, awesome!

MHD: Until I was about 16 years old, and I didn’t come from a good Muslim home. I went to Catholic school; my grandparents were Christian, they hated my mother for converting, they took me to church with them on Sundays, so I had this whole going to the mosque on Fridays, and then going to Church on Sundays. It wasn’t a problem, but I did a lot as kid dedicated to spirituality.

KR: We might be more similar than not because I went to Catholic from ages 12 to 16, and I went to mass, and I did all that church stuff with my friends, and with my school. My parents converted to Islam when they were in college, and their families were not excited about it. We’re probably actually more similar in our upbringings than not.

MHD: Wow.

KR: I think that for most African-Americans who are in the wave of Islam from 1970 on, they were converts. None of us were born into the faith. A few of us were, but for the most part, we weren’t, so we are always living this syncretic, dual life of being one foot in Christianity, one foot in another thing that we haven’t defined, and one foot in Islam. I think that’s kind of beautiful because it’s residue.

MHD: Yes.

KR:Nothing ever gets erased, right? I mean, there’s stuff that I remember growing up with my grandfather. He respected that we were Muslim, but he didn’t want us to feel left out when he bought Christmas gifts for all the other kids. So he would bring us Christmas gifts on the 26th, but they wouldn’t be Christmas gifts – they would be winter gifts. But we all knew they were Christmas gifts, so there was an understanding that we weren’t celebrating Christmas, but we were because our extended family wanted to still include us in those traditions. And my parents also grew up with that for 30 years, and they were still attached to those traditions as well. So I don’t think they ever leave, they just sort of linger as a residue. It’s visible.

MHD: Yes.

KR: I like it. I don’t know; I appreciate the upbringing and that wasn’t so orthodox.

MHD: Yes, and I do too. I tell people that all the time. I remember people saying, “Oh, you must have been confused,” but I’m like, “No, not really.”

KR: No! Yeah, exactly.

MHD:I understood it all and I never had a problem with it.

KR: Yeah.

MHD: Does your faith have any place in your work?

KR: Yeah, and it’s a question people ask me a lot because they’re like, “Your work seems very Black, but then we don’t see the Muslim part of it.” For me, I feel like when it comes to my spirituality, it is a very private practice for me, even though it’s visible in my appearance, and visible in my clothing, and visible in my name, and visible in so many other ways. But I feel like where spirituality comes through in my work is in my methodology, and sort of my fixation around making sure that my work is focused on issues that affect people who are marginalized. A lot of my work is influenced obviously by Prophet Muhammad and his work that he does around social justice and ensuring that the people who don’t have a voice do have a voice. A lot of my work is speaking to that. I also feel like this is the same thing about being a Black artist – people expect your work always to be super-super-uber Black. I think there’s the same pressure for Muslim artists to be super-super-uber Muslim.

MHD: Yes.

KR: I like the flexibility of being able to create work that is reflective of where I am at that point in time. That may mean at that particular time I’m focused on my Blackness because a bunch of Black people is being killed right now, and that’s my focus. There may be another point where my focus is really about me being Muslim because that’s just where I am. I don’t think they’re ever divorced from one another; I just think some things come out because there’s some urgency around certain issues at certain times. And they all intersect, obviously. I was stopped. It wasn’t allowed. Why? Because I was Muslim. That obviously is something that I need to deal with, but that’s going to take me time to process and deal with. I’m interested in not always being so reactive, where every time something happens to a Muslim person, or a Black person, I need to respond. But trying to think about how do I use the spirit of what I’ve been taught as a Muslim to fight for social justice. How does that impact the type of work that I create, and when I create it, and for whom I create it?

MHD: Yes. I saw your post (on Facebook) about that when the incident happened. I tagged an attorney that I know and hoped that he would be able to help you out in that situation.

KR: Yeah.

MHD: I was appalled that this is where we are in 2016, 2015. We should be so much more evolved than that at this point.

KR: My opinion on this entire situation, it was horrible and humiliating, and I missed my vacation that I paid for.

MHD: Wow.

KR: But I think more than anything, it’s a good reminder that we often look for these visual cues that things have gotten better like we have a Black president, or there’s a Muslim girl who can box. And we’re like, those are cues that systemically and institutionally things are better, but I also find that those things are distractions from the fact that we still have large amounts of institutional work to get done. What I even think about my work, a lot of it is work that gestures and points towards the idea that history is messy. There’s never going to be a point in history where some of the horrible things that have happened in the past are not going to show up and remind us that we still haven’t gotten that far.

That’s what that entire incident showed to me. But I think that I’ve only been alive for 30 years, but in the 15 years of where I feel like I’ve been conscious and cognizant of what’s been going on, I feel a lot of things are cyclical. We get to a point where we think things are great because we have some symbol that represents things have changed, and then we are shocked into reality by the fact that something else occurs that reminds us that we haven’t moved as far as we thought we moved.

MHD: When you create, and this could be whether it’s your art, whether it’s the writing that you do-how do you prepare for the act of creation?

KR: There is no actual ritual involved because I, as a full-time artist, I also have a full-time 9 to 5 job. A lot of what I do has to fit around the reality of capitalism, which means that I have to do multiple things simultaneously to sustain myself, but also to do my art. A lot of times it will be like, I might be sitting on a train and hear someone talking, and that might trigger something. Or it might be just like decompressing after a day, home from work, and I see something on television, and that might trigger something. So a lot of my preparation for work is being attuned to everything and just keeping all my senses active. I’m always listening to what other people are saying on the train. I’m always looking for something; I’m always reading something. I’m never looking for something in particular, but I’m always open to the possibility that I may come across something in a space that I didn’t imagine that I would that might be useful for my work. There’s a lot of times that I’m on the train, and a dude who wants to give a sermon is giving a sermon, and I’m listening to that sermon very, very closely because I’m just being attuned to that, and there’s something in what he says that may have an impact on what work I go home and do later. I think most of my preparation is just being open as much as possible to whatever sensory influences might be available to me. New York City is a great place for having all of that available to me.

MHD: Right now, African diaspora art is very popular.

We see there’s so much buzz about Africa Diaspora artists. What are your thoughts about this new popularity among people who don’t look like us and the way they view our art?

KR: I have many opinions. I think it is great that people outside the community of African folks and people in the diaspora recognize that Black folks make art, and we make damn good art, and we are talking about relevant things and beyond talking about relevant things, we’re making an aesthetically beautiful work. I think that’s important that people recognize our work as fine art, as aesthetically beautiful art. I think what gets problematic is when we get pigeonholed as Black artists who can only make work about Blackness.I’ve been reading a lot about abstract artists who are making work that might be implicitly about Blackness, but because it is not directly saying something about Blackness in a way that’s palatable or easy to understand for another audience, they’re being deemed as not Black enough; artists who are not concerned about themes and their Blackness. I think that with recognition comes greater scrutiny. So yes, it’s good to be recognized as a community of people who are making art, but with that recognition comes greater scrutiny around who is and who isn’t a Black artist.

Also, there’s always the danger of being co-opted into conversations that either further erase us as Black artists, or can have a tendency to homogenize us a just a group of Black artists who are just doing this sort of thing. I think it’s important for Black folks to be aware of that, and to be aware of what means, but not allow that to dictate the type of work that they make. I think that what can also happen is that you’re constantly concerned how outsiders, the people who are not you, are looking at your work. So you start to change the scope and the narrative arc of your work to make it more palatable. I think you should keep making work that you want to work on, but also recognize the role that we have played in presenting our work to make sure that the message that we intended is still understood and visible, and isn’t being co-opted in any way.

MHD: You have three shows coming up this year that I know of, so far.

KR: Yeah, I have a couple of shows. I have to open up my computer to tell you. I can always e-mail you later about what those are. But yeah, the last two years have been good for exhibiting work, and I’m looking forward to the summer when I’m able to slow down a bit and to process the work that I’ve made over the past two years. Because one thing I am interested in is what does it mean to make a lot of work, but what does it mean to take all of it apart and figure out what parts of each body of work, or the residue of each body of work and to use it to create new work. So I’m looking forward to the opportunity not to bury my work, but to tear it all apart and then try to reconfigure it into a new body of work. So I’m excited about slowing down, and digesting, and processing, and just spending time thinking about what I’m doing. Thinking more deeply.

MHD: Can you tell me about them?

KR: “At Home in the World” opens up in New Mexico on February 6th and it’s an integration of “No Instructions for Assembly,” which was a project that I started back in 2013, because my family was homeless for about a decade and in the process, obviously you lose a lot of stuff; the most important to me was we lost a lot of family pictures, and family heirlooms, and just other material culture that sort of signals our existence in the world. So when I was really young this really concerned me because I was like, “How will anyone know that we were here?

MHD: Wow.

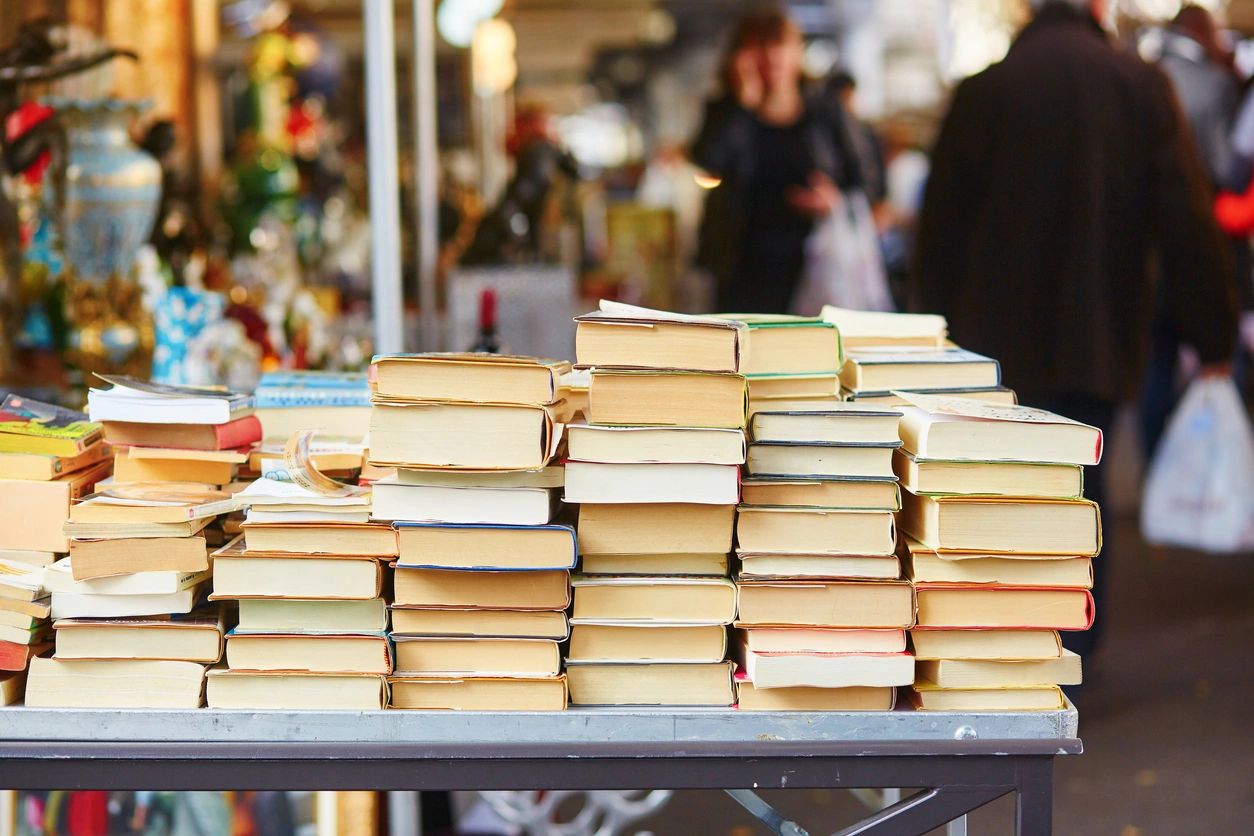

KR: My concern was how will anyone know we existed? Around that time I started trying to gather up whatever pictures were available of my family, and then I also just started collecting other little small things that I thought might be a signal that we existed. Even if it was an old ragged piece of clothing or just small, random bits of things. As I got older I started going to estate sales and flea markets, and searching on Ebay and finding a lot of pictures of Black families. They didn’t have to be mine, but I was looking for pictures of Black families, and I was looking for pictures of Black families that felt familiar to me. So I found pictures of girls in yellow dresses, so I could get a picture of me in a yellow dress, so I would buy things like that.

The show “At Home in the World” is a group show where I’m installing sort of an archive of my family history using both my family’s pictures and ephemera, as well as found family pictures of Black folks and ephemera. I’m installing it in a gallery space that’s going to slightly mimic a domestic space. It’s a gesture towards domestic space but it’s going to be really an archival display of those images.

That show will be up at the same time another show opens in Brooklyn at BRIC called “Whisper and Shout” where I will be rebuilding my parent’s living room from my childhood using found furniture and other things. Also, there will be a video that loops portions of Black family sitcoms as almost like a 30-minute video room that people can sit and watch and engage in the furniture and space. I’m really interested in domestic spaces and creating the domestic space that I grew up in using found furniture and ephemera.

No Instructions for Assembly, IV by Kameelah Rasheed

MHD: If music and literature inform your practice, name 3 that are guaranteed to instantly inspire you.

KR: There’s a writer, she’s a poet, her name is Harriet Mullen, and anyone who talks to me is probably annoyed with me at this point because I talk about her all the time. Harriet Mullen, definitely, she’s an amazing poet, and she’s just amazing. Octavia Butler, I met her when I was 17, and she signed my copy of Kindred. It was the first Black science fiction book I ever read, and it was assigned to me as part of my college summer reading. I met this Black woman, and I was just like, I don’t know who you are, but you are an amazing being. So anything that she ever writes, anything that she ever touches, even listening to her voice in interviews, that is a moment where I could, so many things that kicked into high gear.

MHD: Any music?

KR: Aretha Franklin. We got our first snow here ( New York), and I was talking to a friend in South Africa and he was like, “Have you heard this song by Aretha Franklin?” And I was like, “Which one,” and it’s called ‘The First Snow in Kokomo.’ and I listened to that song, and I was like, that is a beautiful song, and I went back, and I started listening to everything that she had ever sung. I was just like, wow. She just moves. She just moves your spirit in a way that makes you feel like you can power through an all-nighter.