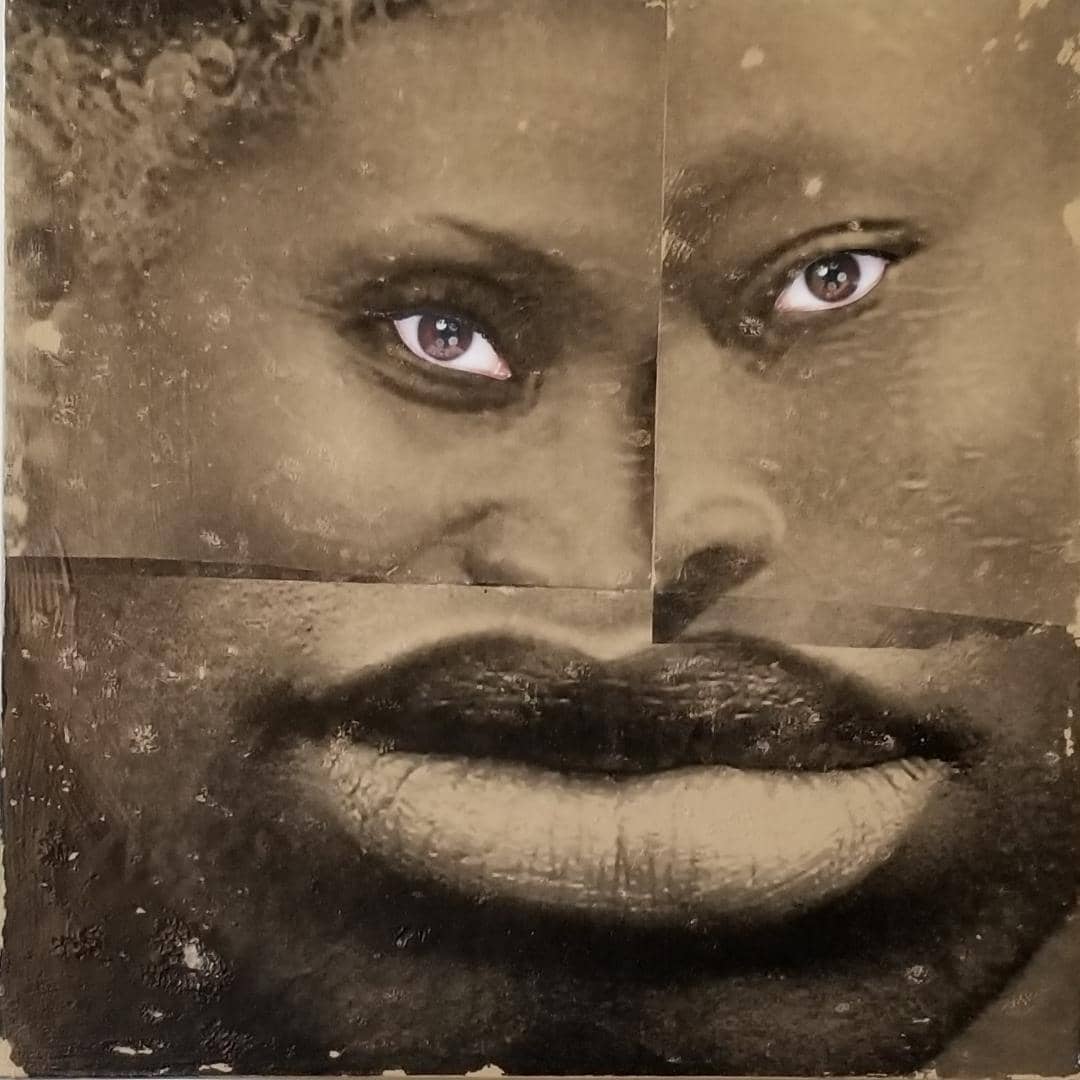

Above: Detail from “Secrets, Refuge, and Safety” installation. Phototransfer collage on wood. 14″ x 14″ x 5″.

The prolific work of multimedia artist Candace Hunter is rooted in her identity as an African American woman. Her pieces transcend binary accounts of race and gender, excavating nuanced intersectional themes that connect with history, memory, spirituality, and society. In a 125-year- old coach house nestled in Chicago’s historic Kenwood/ Hyde Park neighborhood, Hunter blends the comforts that come from a loving family with her studio practice. Her home is a studio of sorts that represents her ever-evolving art practice. Hunter is a seasoned artist who approaches new projects with the vigor and excitement of an ingénue, breathing fresh life into all she does. Hunter’s home studio houses paintings, sculptures, installations, collages, past works, current works, future plans, along with everything in between. I had the privilege of catching up with Candace in her studio-home, as her loving partner, artist Arthur Wright, served us tea and constant laughter during the visit.

Hunter humbly describes herself as a visual artist, and collagist, however, it is her activism with water rights that informs some of her most powerful work, transcending the visual to the poetic, often giving voice and narrative to issues that are complex and difficult to communicate.

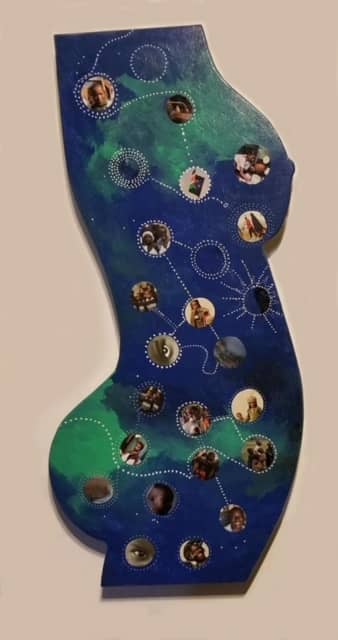

Above: Mother and child torso from “Dust in Their Veins”, mixed media, 20″ x 30″.

“I’m always excited to share with people issues of water,” she said referring to her profound exhibition Dust in Their Veins: a Visual Response to the Global Water Crisis, currently showing at the University YMCA Gallery in Urbana/Champaign, Illinois. Always on the hunt for new opportunities as an artist, Hunter entered a juried competition for a grant from the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis), called Women and Water Rights: Rivers of Regeneration. “But what are water rights?” This was the inquiry that propelled Hunter down a long line of research, leading her to a devastating societal and global issue, an issue that she quickly learned largely affects children and women of color, women who look like her. India, Central America, and Sub-Saharan Africa are the most affected by the water crisis.

Garnering the research tools she acquired during her graduate studies in anthropology, Hunter attended large organizational meetings about the global crisis but found that she was the only woman of color in attendance. She also found the tone of the meetings to be more about stating the problems ad nauseam rather than critically searching for solutions. The underrepresentation of black women involved with this global issued spurred Hunter to host small meetings in her home with astute women she knew. In these meetings, women of color uncovered details about the issues of water and discussed how the imagery of this crisis should be presented in Hunter’s work for the competition. Hunter was immediately compelled to counter romanticized thoughts concerning women in developing non-western countries.

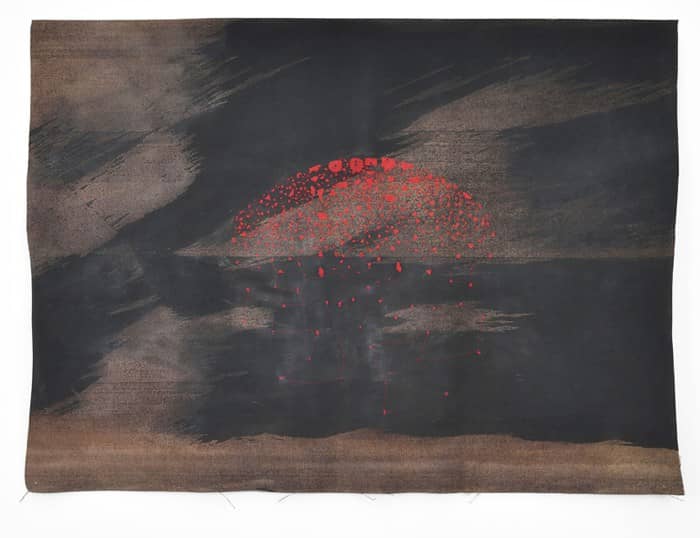

Above: Installation details: “Dust in Their Veins”, DuSable Museum of African American History, 2014.”

“I wanted to get away from stereotypical images of the brightly dressed, curvy woman, with a basin on her head, beautiful fabrics ties around her hips, romantically sashaying through the desert in long undulated movements in search of water. Someone is walking ten miles a day, every day. There are no vacation days! Every day you’re walking ten miles a day, and you must fetch it, and bring it back (home), and then you have to boil it. The water is used for cleanliness, but first, you have to sterilize it so your baby won’t get dysentery!”.

The reality of these women, brought about a greater sense of urgency, as Hunter attempted to develop imagery that would not only give a more realistic account of life under these constraints but also create a surge of empathy that would encourage more people to get involved. Hunter studied the dense notes from two large international meetings concerning water, one in Belgium, the other in Buenos Aires that occurred four years part. “ I realized that women who were truly affected by the lack of clean water were never in these meetings, their genuine voice was never heard, that women were not able to leave her situation.” The result was a headless, legless torso in the movement that originated as a two-dimensional form. “I wanted this torso to move for her, and speak for her.”

The original work consisted of ten torsos lined up in succession; diminishing in size from thirty inches to four inches, largest to smallest. The images incorporated hues of blues and green symbolizing water, along with ribbons of red representing the blood of these women, but as life is challenged due to the lack of clean water, the blue colorization appears less and less until it becomes a small dot. The bellies of the torsos vary from large to small, as questioning expressions of life and death. Is the torso pregnant, or is the trunk bloated from dehydration? These images did not make it into competition in Minnesota, but Hunter’s quest to bring this crisis to the forefront of her work was only in its beginning stages.

The vigor of her water crisis research became the impetus for an ongoing project that has expanded and morphed into a critical body of work that has been showing with various institutions since 2012. She chose Wenge wood from the Congo region of Africa, along with other exotic woods from places where the issues of water are the direst, to create the most recent iterations of the torsos in three-dimensional forms. The first showing happened at a warehouse gallery in the Pilsen Art District of Chicago. She built a water well to incorporate in the exhibition along with a tree stump that becomes a makeshift sitting place symbolizing a moment of rest and the communing of women between long, tedious journeys of collecting fresh water. She collaborated with other artists to create soundscapes poetry, resulting in an emotionally moving show the placed the viewer in the situation of the women depicted. Dust in Their Veins: a Visual Response to the Global Water Crisis, has shown at several places in Chicago, and throughout the United States continually bringing about more awareness and activating change. One of the oldest American institutions of black culture and history, The DuSable Museum of African American History, in Chicago, Illinois, exhibited Hunter’s water women and extended the exhibition twice. The Avery Institute in Charleston, South Carolina also showed her work, bringing more attention to the work. She raised funds for the exhibition by crowdfunding, and always wants to show the original work as an exhibition for viewing rather than for commercial gain. Written factual information about the global water crisis is displayed along with images, bringing greater contextual awareness for anyone who engages with them.

Above: Constellation torso from “Dust in Their Veins”, mixed media, 20″ x 30″.

Water is a recurring theme in Hunter’s milieu. Her current working-project is based on bringing the history of the Middle Passage to the visual field. Currently, she is working on installation works that involve large, monumental manipulations with fabric where she cuts thousands of holes in felt, representing the lives lost during the Middle Passage, the horrific oceanic journey of the Transatlantic Slave Trade between West Africa and the so-called New World. Through this process, Hunter is again is attempting to bring story and narrative to an under-theorized historical phenomenon that represents her own identity. Hunter’s most recent work Loss/Scape, A Landscape of Loss, will be showing in the Fugitive Narratives exhibition – Opening mid-April 2018, at The Hyde Park Art Center, in Chicago, Illinois.