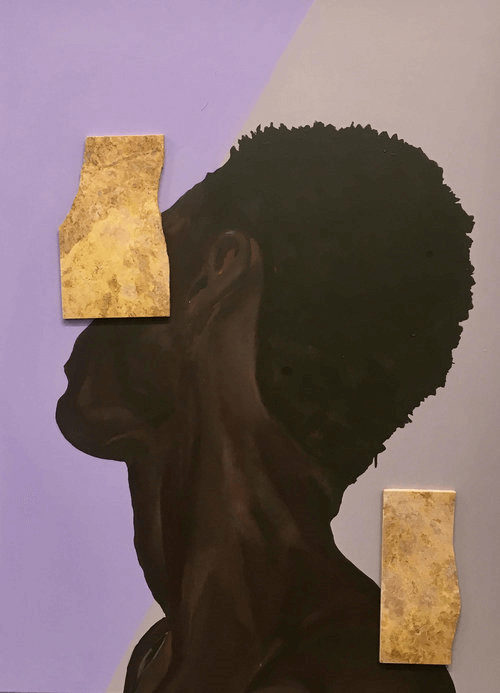

Above: Ozioma Onuzulike | Chronicles of the seasons | 2023 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

The Fourth International Conference on Water in Africa kicked off on March 18 at the Institute of African Studies on the University of Nigeria’s serene campus in Nsukka (UNN). Ensconced between the Faculty of Social Sciences and the Vice Chancellor’s office, the Institute comprises various departments, including its ethnographic unit, graduate teaching center, research library, and museum, which is located on the ground floor of a one-story building.

At the conference, an elaborate mix of artists and academics across different disciplines gathered for an art exhibition commemorating the fourth annual event. Most of the featured artists, including both curators Ugonna Ibekwe and Ozioma Onuzulike, are homegrown talents, alumni and staff of the host university. Their art pieces included poetry, sculpture, painting and ceramics.

The conference was organized by Our Water and Health Network Africa (OWHN Africa) and the Water and Public Health Research Group at UNN. Heralded by a call for abstract submissions on several subthemes about water, the art exhibition was held on the second day of the conference. It was well publicized by the museum’s PR team and OWHN Africa, with free entrance on opening day and a nominal fee thereafter.

According to Ibekwe and Onuzulike’s curatorial statement, “water is fundamental to all life and productivity, yet its availability and purity have become increasingly fragile in our modern world. Human technological advancement has led to widespread pollution of water bodies, even as climate change rapidly alters water cycles globally, rendering access to clean water uncertain for many communities. Through a selection of poetry, paintings, digital collages, sculptures, ceramics and installations, the featured artists and poets engage with the complexities of water from the dimensions of its presence, absence, and shifting meaning in a time of environmental crisis.”

The exhibition was an art form in itself. The assemblage of art pieces was distributed evenly across the museum’s three halls—contiguous and open to one another, providing visitors with a seamless viewing experience.

A speech and tour by Professor Trixie Smith, a scholar from Michigan State University, opened the exhibition. After this, one of the curators, Ugonna Ibekwe, provided explanatory context for the pieces on display. The opening tour was attended primarily by scholars from the sciences with interesting opinions. One remarked that Eva Obodo’s charcoal lumps in Gifts for the People were reminiscent of charcoal’s traditional role in water purification, while another asked Ugonna Ibekwe about the white strings around the maize-cob forms in Lying in State, to whom Ibekwe explained that they signify bondage.

The first hall, which was also the entrance, bore printed poetry and digital collages on opposite ends. Lightweight pieces occupied this space under evenly distributed lighting, inviting a gentle entry into the theme. The second hall displayed woodwork and ceramics with an infusion of mixed media. The third hall presented viewers with an interesting twist; a site-specific installation of bottled water inlaid with broken ceramic forms. It was commissioned specifically for the exhibition to demonstrate how water embodies history, recalling the harrowing trans-Atlantic slave trade.

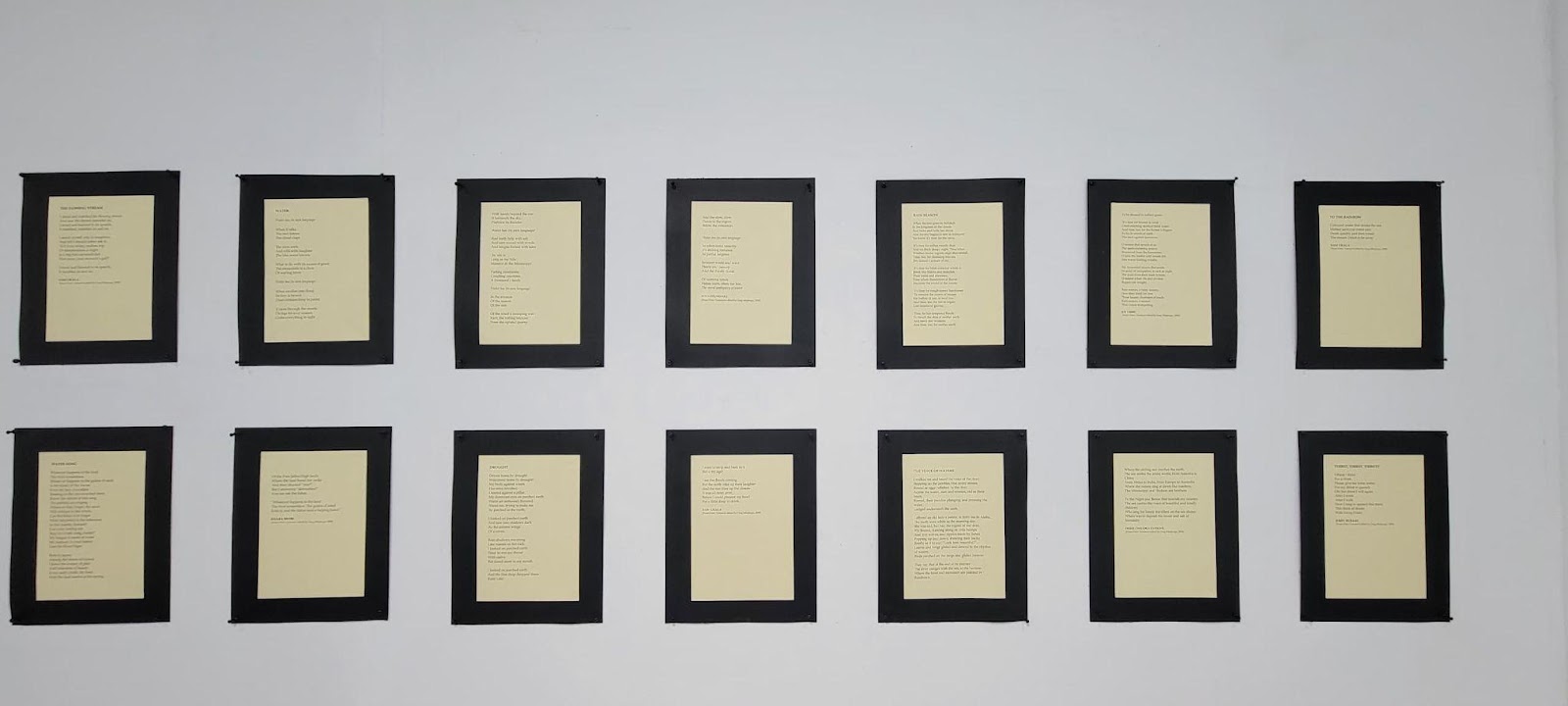

Printed poetry by several poets on display | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Featured poets included Niyi Osundare, Esiaba Irobi, Chidi Nwankwo, Ikechukwu Uzo Erojikwe, Pious Okoro, Ngozi Obasi Awa, Florence Orabueze, Ozioma Onuzulike, Sam Ukala, Jerry Buhari, Ossie Onuora Enekwe, Joe Ushie and Greg Mbajiorgu.

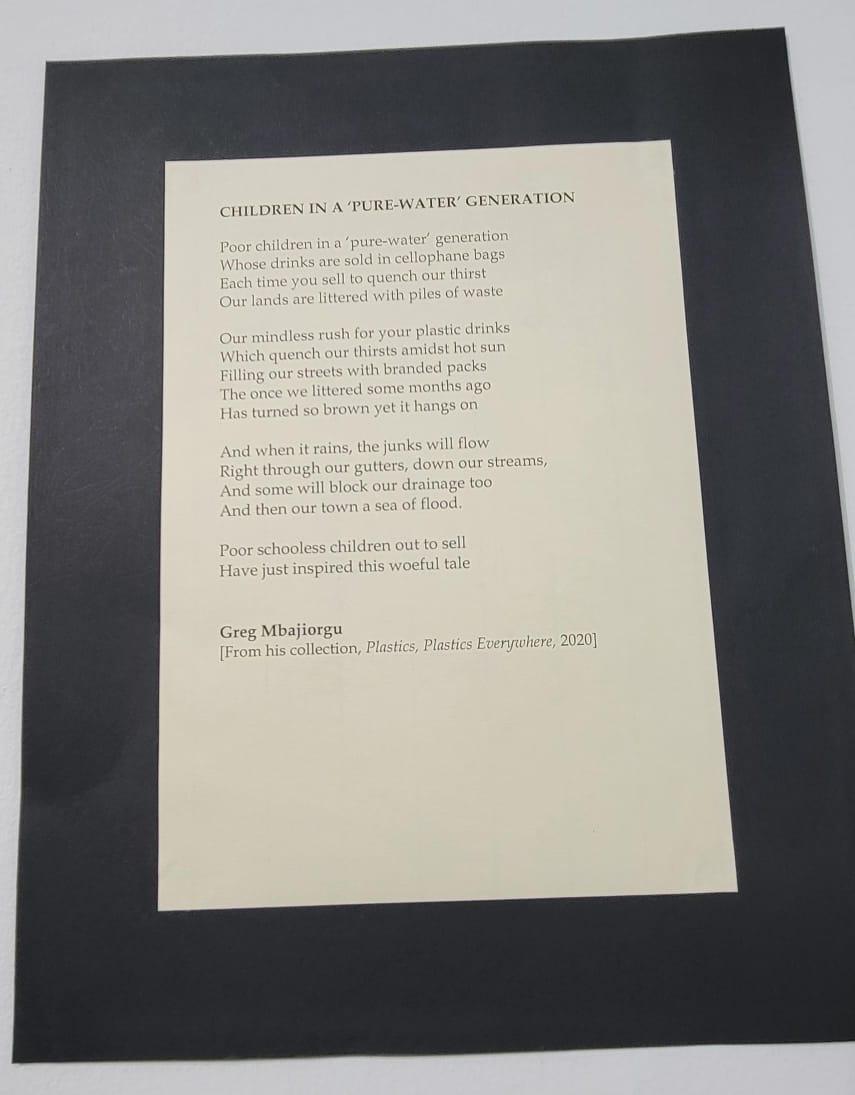

Their poetry, selected from published anthologies and collections, jointly expressed the never-ending effects of drought and the inherent urge to quench thirst. Through vivid imagery, Greg Mbajiorgu’s pieces tackled dual issues: unsafe drinking water and the menace of plastic waste.

In Children in a ‘pure-water’ generation, he presented the cycle of water insecurity in Nigeria: sachet water is peddled to pose as a solution to unsafe drinking water. However, its disposal is grossly mismanaged, resulting in clogged drains by plastic waste and eventual contamination of streams and rivers, which are often the sole sources of drinking water in underdeveloped neighborhoods.

Greg Mbajiorgu | Children in a pure-water generation | 2020 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

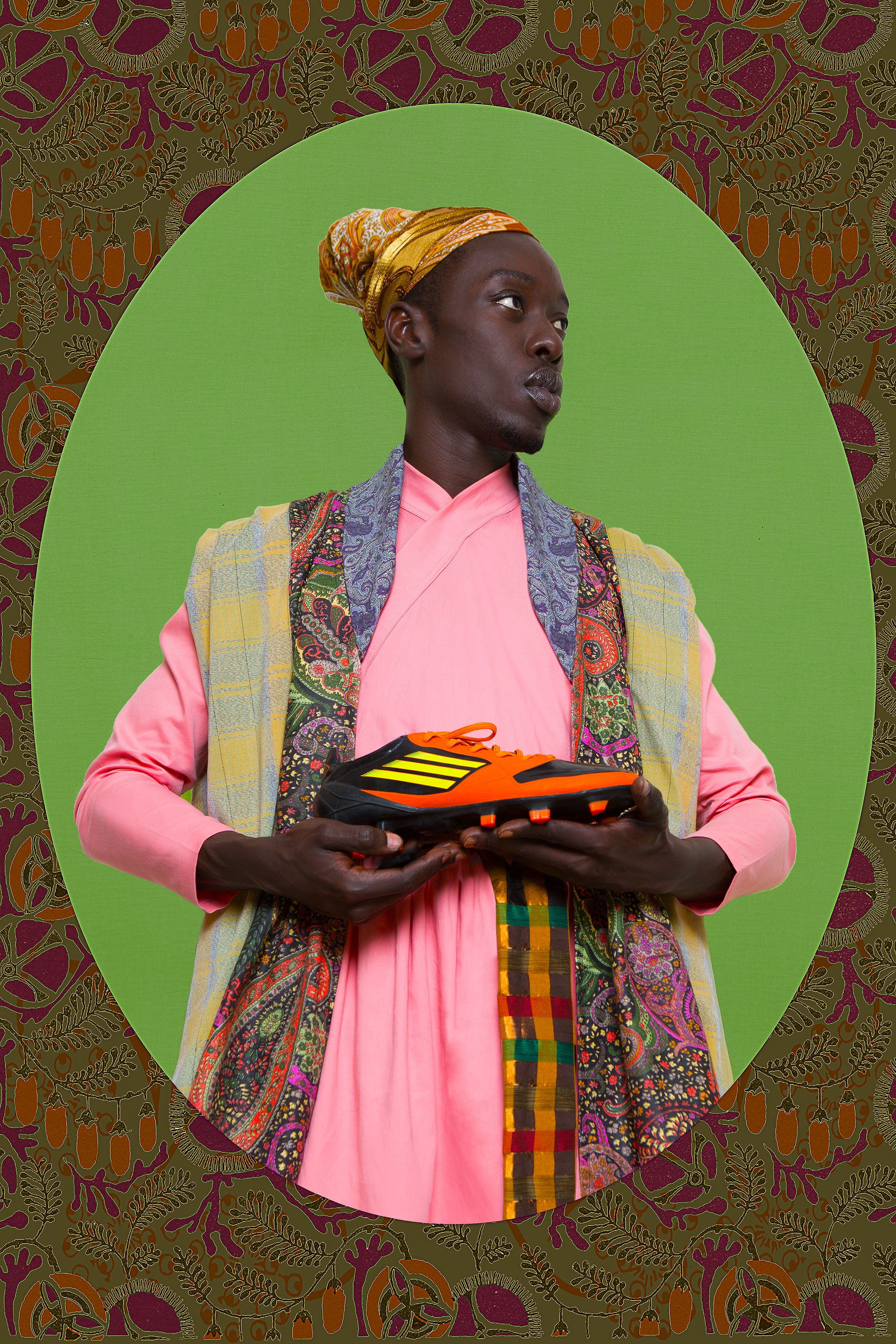

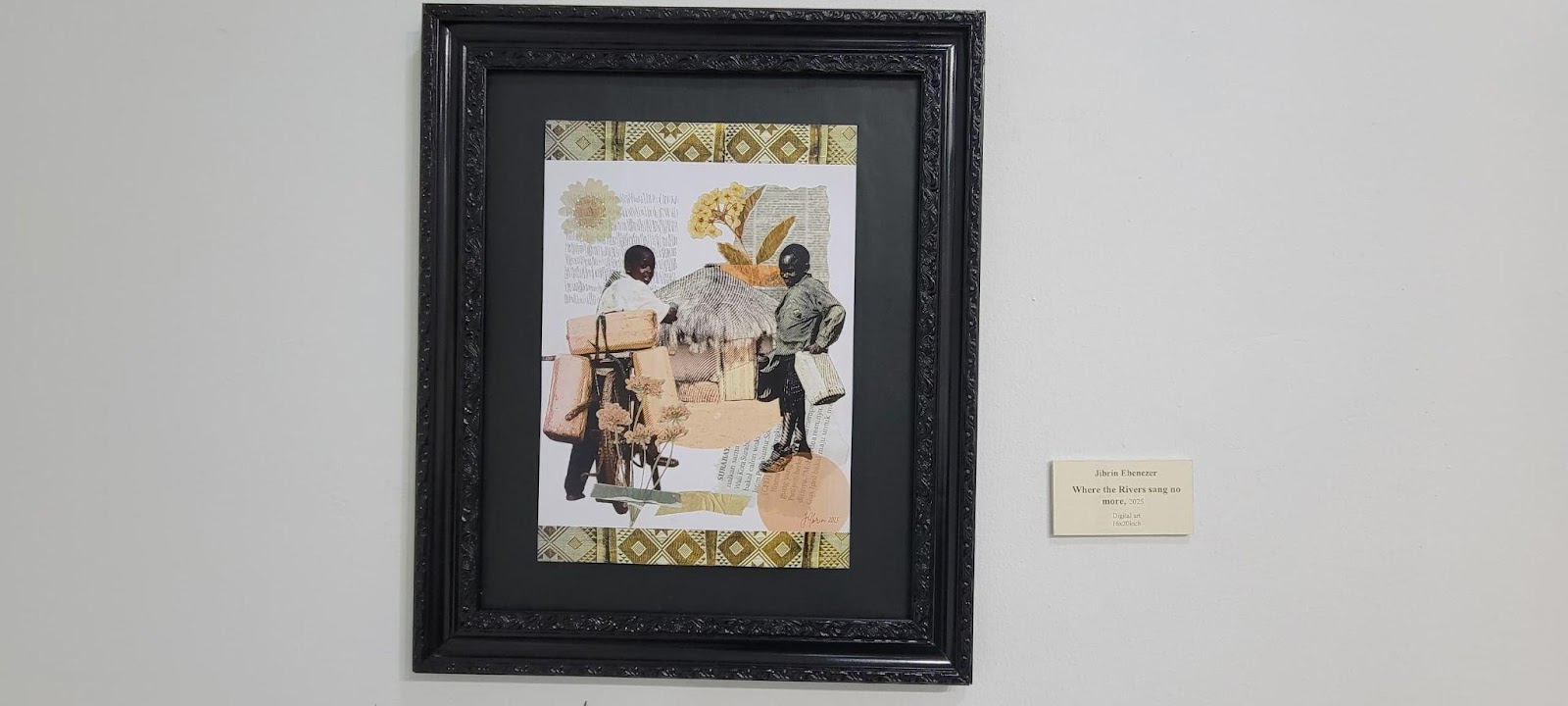

Jibrin Ebenezer’s digital collages are strikingly similar as they carry an overall message. The picture frames encapsulate original photographs edited to include newspaper clippings written in Bahasa Indonesian and iconography.

Jibrin Ebenezer | Songs of the yellow gallon | 2025 |The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Each frame shows Black people, mostly children, fetching water with yellow gallon containers and transporting them on their heads or with bicycles and motorcycles.

Jibrin Ebenezer | Hands that shaped rivers | 2024 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

This is common in localities where individual compounds have no running water and have to source water at a centralized spot located at the community center, along with their neighbors.

Jibrin Ebenezer | Where the rivers sang no more | 2025 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

These depots are either privately owned, funded and maintained by a non-governmental organization or the government.

Goodness Nnabeze | Akpa mmiri m | 2024 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

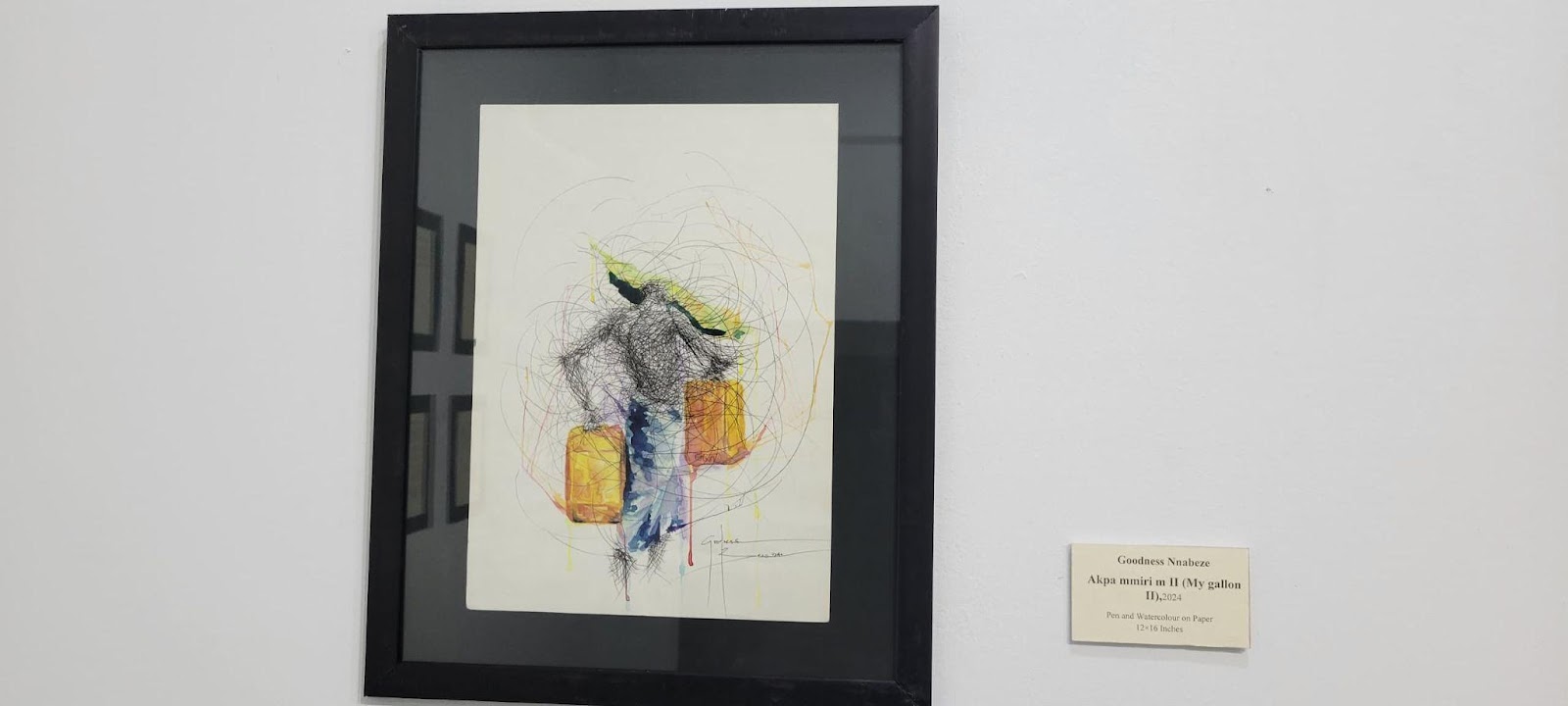

Goodness Nnabeze’s pieces are primarily pen art. Akpa mmiri m loosely translates to “my gallon.” Akpa mmiri m I and II are immersive, engulfing viewers in a personalized depiction of the character’s plight as the female form struggles with yellow gallon containers filled with water.

Goodness Nnabeze | Akpa mmiri m II | 2024 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Akpa mmiri m I and II seem to deliver the same message as Jibrin’s pieces, even though they use different media.

Ozioma Onuzulike | Chronicles of the seasons | 2023 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Onuzulike crafts this piece with earthenware and stoneware clay, and its shiny luster comes from the use of iron oxide engobe, ash glazes and recycled glass. Yam barns in Igbo culture are an indicator of hard work, wealth and sustenance. Large barns can feed polygamous family settings well into the next harvest season. Chronicles of the seasons is a glaring illustration of a scorched yam barn, foretelling hunger and lack.

Eva Obodo | Gifts for the People | 2018 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Eva Obodo’s Gifts for the people is a masterful combination. An unruly congregation of charcoal lumps is held together by colorful copper and aluminum wires. Gifts for the people directly showcases the damning effects of bush burning, with causative effects being linked to drought.

Ozioma Onuzulike | Deserted Hives | 2023 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Onuzulike uses Deserted Hives to enforce realism, as its visualization directly captures the essence of the title. Bees rarely abscond from their hives, except due to unfavorable conditions, which include a lack of water and forage.

Chijioke Onuora | Transitions I | 2024 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Onuora’s expertise in woodwork and sculpture is evident in Transitions I, which is part of a series not included in the exhibition. This intricately detailed piece closely resembles a closed frill curtain silhouette. It conjures the hushed feeling experienced just before sunrise, representing a fresh start.

Ugonna Ibekwe | Lying in state | 2025 | The Institute of African Studies, UNN | photo: Rejoice Anodo

Lying in state is Ugonna Ibekwe’s ode to the victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, particularly those who drowned in the Igbo Landing. Made with fired clay in the likeness of maize cobs and tied with white strings, half submerged in water, it is a bold attempt to revive discussions about the unforgettable effects of the slave trade and the extreme measures the captured undertook to avoid enslavement.

These pieces, on display from March 19 – April 18, resonated deeply with the conference’s theme: Water and the SDGs in Africa: prioritizing clean water and sanitation, zero hunger, and climate action triad. The digital collages and line art pieces portrayed the lengths people are willing to go in search of safe drinking water, while the ceramic works presented an image of life without water.

Water is essential for life, and safe drinking water is needed for healthy living. With the joint effort of this art exhibition and the conference, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for clean water can become a reality for Africans.

Multiple keywords