Through camouflage, green-screen skin, and a raw, vibrant red, Clarence Heyward’s gazes draw parallels between invisibility and violence projected onto Black men.

In a quiet corner of the Richard Beavers Gallery in Brooklyn, N.Y., owner Richard Beavers adjusted a projector, preparing to showcase Clarence Heyward’s solo exhibit, American Fiction. The space, apart from his marketing associate, was empty—a fitting setting for a conversation about identity, perception, and the realities of Black men in America.

Beavers’s dedication to Black art moved him to call Clarence Heyward and discuss his exhibit, American Fiction for Sugarcane.

Heyward, a North Carolina-based artist, uses color theory and composition to explore how society projects its ideas onto Black men. His work, on display from Feb. 8-March 22, reflects an internal perspective looking outward, challenging stereotypes and expectations.

American Fiction is a visual narrative of tragedy and resistance. In one piece, a Black father sets fire to the White House in defiance of imperialism, leaving his daughters to rebuild. While the series does not explicitly critique gender roles, it highlights the expectations placed on Black men with striking intensity.

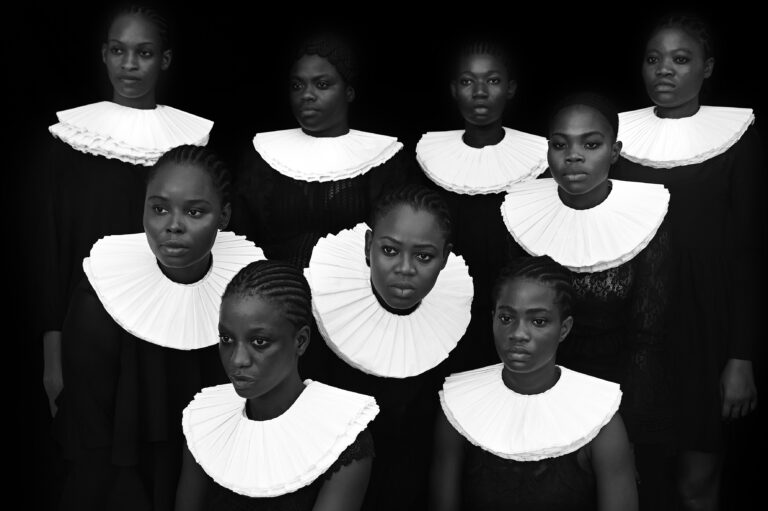

Throughout the exhibit, Heyward’s figures, including a green giant, appear weary, their exhaustion as visible as the green hue coating their skin. This color choice references chroma keying technology—the “green screen” commonly used in film and media—symbolizing how Blackness is shaped by external narratives.

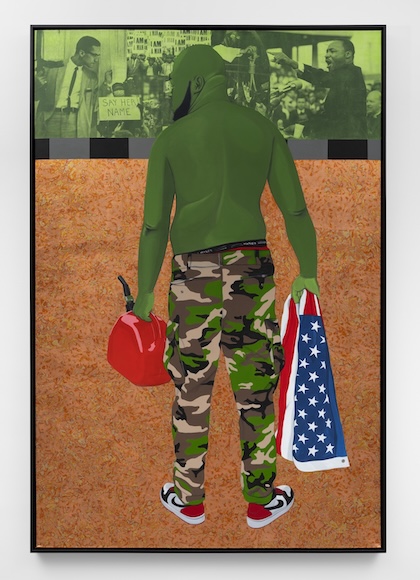

The less-than-jolly green giant glares from large canvases. He’s only looking at you in America’s Most Wanted, Super-Villain, and NWA, through camouflage masks, and in American Fiction with a red gasoline canister in front of a burning White House. In We The People and Bound, he’s not looking at all.

“Media, social media, movies and TV use it [green screen] to shape the perception of what’s really there,” Heyward said. “I use that as a metaphor for Blackness. I feel like Blackness has been shaped through the lens of the media. People see Black people as they’ve been shown or told we are.”

His paintings depict men staring through camouflage masks, gripping a gasoline canister before a burning White House, or looking away entirely. Through green-screen skin and vivid reds, he connects themes of invisibility and violence, illustrating the tension between identity and perception.

The aftermath of American Fiction is implied in The Fire Next Time, where Black women are left to bear the consequences of destruction. Should they rebuild or demand something better? If revolution is necessary, who pays the price?

Heyward’s Memorial Day completes the series, prominently featuring retro Air Jordan 1s in Gym Red—a symbol of both Black cultural identity and the stereotypes that confine it. American Me continues this theme, depicting a vulnerable Black man behind the American flag and the masks he wears to navigate society.

His work does not condemn these representations but acknowledges them, highlighting the tension between self-definition and societal expectation. To be passively Black is to accept stereotypes; to be actively Black is to define oneself despite them. This philosophy aligns with the African philosophy of ubuntu: “I am because we are.”

In American Me, Heyward looks back while being seen. His pessimistic martyrdom fantasy suggests that African American men’s role is dying for the future they can’t join. His work questions whether Black men must always sacrifice themselves for a future they won’t be part of. Who demands this sacrifice?

“She’s bound to the house, so she doesn’t have shoes on her feet,” Heyward says of one piece. “Her job is to care for the kids while I leave. And I’m the sacrifice.”

A Black person’s sacrifice is a self-destructive tradition. The traditional Black man is patriarchal. A patriarch maintains the nuclear family and is the primary authority in the status quo. The nuclear family, which dates back to 13th-century England, grew popular in the 1950s.

Black men have long been cast as protectors, bound to an outdated patriarchal ideal. But what if fire, instead of destroying, could warm a home, sear a wholesome meal, bridge vulnerability in the heat of a hug or ignite hope? Heyward’s art suggests that Black men are not characters in a predetermined story. They have the power to live for their communities rather than die for them.

Why be green when you can be Black?

American Fiction | Clarence Hayward on view at Richard Beavers Gallery in Brooklyn until March 22, 2025.