From outside the Brooklyn brownstone at the threshold of Plastic On The Sofa: The Interior Lives of Black Folx night was hushed by the inside’s ardor. Exiting visitors and those taking fresh air breaks bordered the exterior staircase that led to the apartment’s door. To enter, you had to text someone who would personally welcome you. The front door’s head shelved stained glass and opened to a warm wood staircase leading to the HAUSEN gallery on the second floor.

The exhibit opened on Oct. 5 and will be open by RSVP at info@hausen.co through Nov. 20.

Plastic On the Sofa: The Interior Lives of Black Folx wanted to take the audience to a cultural center that’s the source of interdisciplinary creative output: home. Curator Alyssa M. Alexander featured artists Destiny Belgrave, Chantal Feitosa-Desouza, Mark Fleuridor, Clifford Prince King and Cyle Warner to address how multimedia art approaches are impacted by Black interior design traditions. At HAUSEN, Plastic On The Sofa bypasses the institutional ranking of art by expanding art’s scope outside public consumption.

Behind photos curated large and small, HAUSEN’s gallery walls were a buttermilk yellow that fortified both familiarity and nostalgia among guests. HAUSEN expands on curation by selecting aesthetics to hang on walls and choosing the wall colors for each exhibit then it goes a step further. HAUSEN requires every guest to RSVP before entering. That means every guest is chosen to experience the gallery.

“We’ve never turned anyone down and you put it that way. It’s not meant to be exclusionary. It’s meant to help us facilitate better engagement with people. It’s always a pleasure for me,” creative producer and director of programming at HAUSEN, Usen Esiet said. “When I open the door, I introduce myself and the person who I’m welcoming is someone who I’ve responded to personally.”

Plastic On The Sofa was the first exhibit opening that Esiet was unable to attend, although the exhibit is the eighth show that is being hosted by HAUSEN. The exhibit’s name alluded to low-density polyethylene plastic sofa covers used to protect sofas and accent chairs from water, dirt and general wear. By extension, the exhibit honored your grandmothers, aunts and ancestors’ practice of preservation, permanence and protection while magnifying the vulnerability veil through which all are welcomed and adorned with affinity.

The plastic on sofas that people recognize is called “slipcovers”. Before the 1940s and 1950s popularized plastic slipcovers, furniture covers were specially tailored cotton, linen, or cotton-linen blends that helped protect statement furniture. Pre-20th-century slipcovers were status symbols that went as far as complementing the clothes of a home’s host to balance a space. In many circumstances, slipcovers were removed on special occasions to use the furniture as intended.

Plastic slipcovers now immortalize a decades-old tradition of keeping furniture intact in a way that highlights intergenerational closeness. The familiarity is made palpable by the same plastic that protects it from wear over time. According to the Tenement Museum, plastic slipcovers protect furniture and connect African-American, Jewish, Puerto Rican, Irish, Chinese and Italian family identities among the fabric of American heritage.

“Outside the Black experience, there’s an unspoken relationship that our mundane actions inform our practice and journey. How we create is informed by our experiences more than what we cognizantly register,” exhibit curator Alyssa Alexander said. “How we’re taught to move through spaces informs creative outlets.”

HAUSEN’s Plastic On The Sofa alluded to how slipcovers represent a family’s shield of impenetrable love and attention. In Plastic On The Sofa fabric transcends design trends for furniture and lends to the impact of textile works by artists Cyle Warner and Mark Fleuridor. Upon entering Hausen, there are three rooms: the center room and two rooms on its left and right sides.

In the leftmost room, a video projection by Chantal Feitosa-Desouza sliced through the dim room and baked a video essay onto the cake batter walls. The video drew parallels between time travel and immigration by centering on how to travel in any direction creates homesickness for what was left behind. The video showed the tender handling of culturally and temporally present objects like a hair comb, a wicker basket and a collage that used a cell phone image juxtaposed among paper landscapes to make a place. Feitosa-Desouza’s video invited the context of innovating, much like moving through a new space, as an effort for survival.

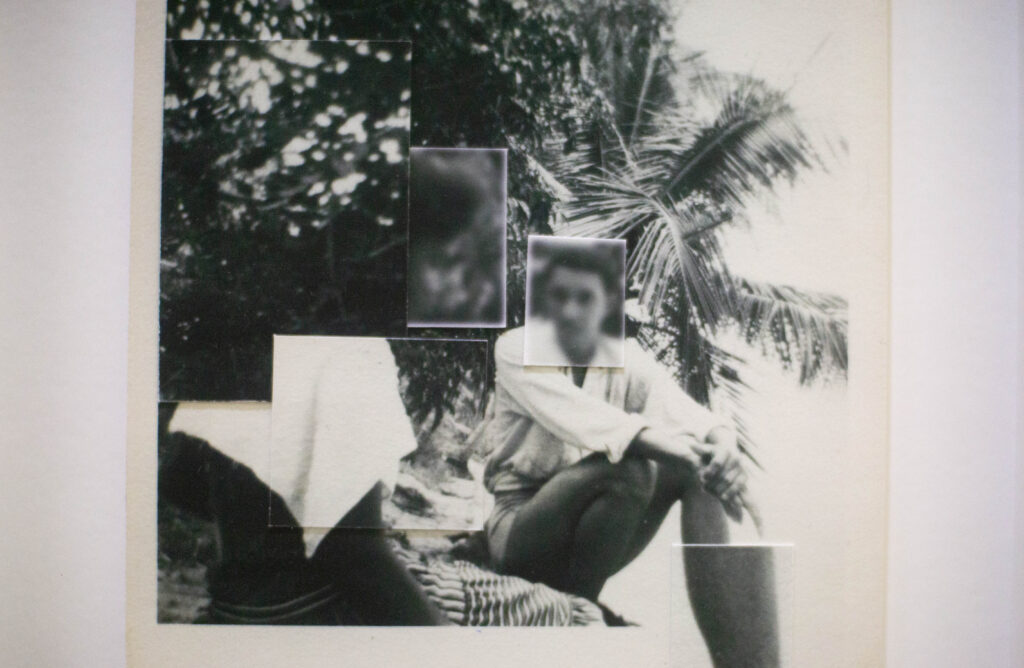

In the corner of the left room, more of Warner’s work hung above eye level. His photos faced each other. The family images with cut and blur-erased faces reflected the anonymity between the familial subjects and the viewer. Warner’s work helped center the exhibit by using time as an element to impose distance between the looker and the looked upon. Moreover, Warner’s images create a similar distance with him for sharing his ancestors in his family’s archive photography whom he never met.

In the center room, the one which guests enter the gallery through, pieces by Warner and Fleuridor both with overlapping textures leaned and hung on the walls. Warner’s textile piece “The Diviner Apparatus” is made of primarily family-given natural fibers like cotton and silk that were dyed and wrapped around a wooden armature. Fleuridor’s piece, Memory Picking hung over the radiator. The blossoms in the pink and white flowers in the flame-colored hand held the memory of flowers that Fleuridor had given his mother as a child. The hand idled over vermillion and lobster reds, raging leaf and amber oranges, and hinted at touches of sunglow yellow. The quilt colors were sewn under thin, contour-threaded lines that looked like fluttering leaves that fell in and out of focus autumn memories.

Across from Picking Memories, Destiny Belgrave’s paintings, Mommy’s Embrace and Daddy’s Hands looked at the audience with clarity. Flush round lips married the pieces along with red underpaintings that gave each piece rosy tints. The gold accents in her pieces alluded to the luxury of nostalgia that was most palpable in the child’s eyes in Mommy’s Embrace. Her pieces were special for cataloging the colors used throughout the subjects, which served to transparently communicate her visual language of memory through color appreciation.

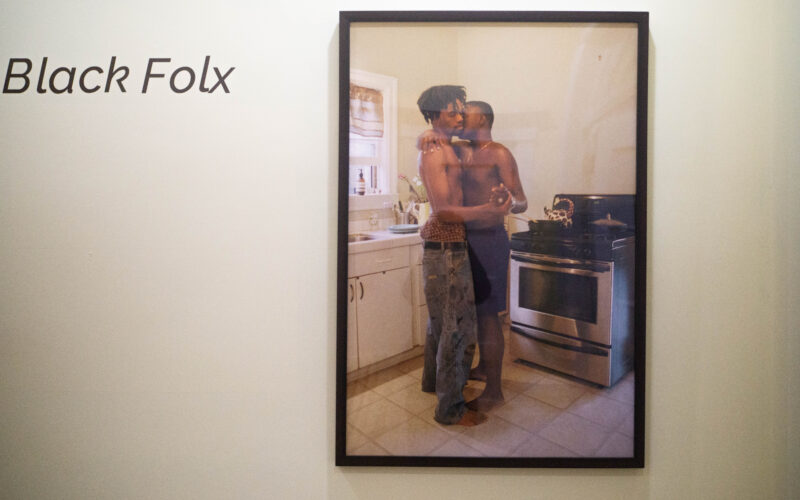

The center and rightmost rooms held masculine gay, firmly gazing and intimately gesturing models captured by photographer Clifford Prince King. His images highlighted control of the subject to appear how they desired rather than having had identities projected onto them. Similar to the gallery’s allusion to plastic on the sofa, the image’s glare protected the models’ confidence and agency to be seen with an idyllic light. The sun-soaked and glaring gold skin of King’s models was given space to breathe in the gallery’s largest room.

In minimal space, Plastic On The Sofa made the home-signifying art approachable and digestible by giving the audience an entry point to reflect on personal experiences. HAUSEN’s creation of a home-bound space helped unify the exhibit’s intention to transcend stratifiers like class, race and location, which shape a language that unequivocally represented home.