Though historically relegated to the margins of western art canons, the creative genius and innovation of artists from Africa and the greater diaspora cannot be denied. Despite this, work created by African artists is often lumped into a homogenous categorization, “African Art” that dilutes the dynamic specificity and individuality of each artist’s contributions. It is crucial to call this out because it is not a framing applied to European artists.

It would be strange to dump all artists coming from Europe, regardless of the cultures, mediums, or concepts they engage, into one categorization called European art. Rather, historians have worked to distinguish specific styles, eras and movements and then engage specific artists within discourses that clarify distinctions among them. To not offer this same rigorous contextualization for artists from Africa and the Global South is not only ahistorical but diminishing. Scholar and curator Chika Okoke-Agulu said plainly, “Even to this day, and despite slow but halting recognition of African artists’ participation in the making of modern art, the ‘out of Africa’ attitude endures.”

Since the beginning of her curatorial career, Touria El Glaoui has worked against the misconception that African artists represent a singular vantage. This misread creates unnecessary obstacles for artists from the Middle East and Africa who hope to expand their access to international markets but are blocked by perceptions that they are all making the same kind of work. When she was growing up, there were few resources for artists in Morocco. Despite this, her father, Hassan El Glaoui, became an internationally recognized artist. His life and extraordinary vision inspired Touria’s trajectory.

“I was raised in arts and in a country where we were missing a lot of infrastructure, and a lot of access to artists, because the museums that are in existence today, when I was growing up in Morocco, they were not in existence,” El Glaoui said. “So, I was very lucky in a way to have my father as my first education and to benefit from his knowledge. His journey in becoming an established artist is a miracle.”

After years of working in corporate America, which enabled her to travel to other countries across Africa and the Middle East, she established relationships with a vast network of artists. She soon realized that there were no pipelines to support those artists in reaching international art markets.

“In 2011 and 2012, not the landscape that we have today, it really intrigued me to understand why artists who were very established in their own country, even the most established ones who had an amazing core locally, did not cross over,” El Glaoui added. “I said, there had to be an explanation for it, and I was looking, trying to find those artists in Europe, but I couldn’t find them. I couldn’t see them anywhere.”

Collectors had to travel to countries in Africa or the Middle East to explore the art ecosystems in those regions if they wanted to learn anything about the artists working there. It was frustrating and discouraging, because each artist was incredibly talented and esteemed in their home country. El Glaoui understood that she could create a bridge to help collectors and African artists reach each other.

Encouraged by her father’s success as an artist and driven by a desire to support other African artists in realizing their goals, in 2013, El Glaoui founded the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair’s flagship edition in London. 1-54 was more than a commercial platform; it was a way to ensure that talented artists were included in the canon of contemporary art.

“The idea of the Fair really became about what could we do to help make sure that people have access, that those artists had visibility,” she continued. “We realized little by little, by putting this project together, that we needed to not only create a commercial platform, we had to educate people on the international art ecosystem and about artists coming from the continent and make sure that we accelerated this inclusion in the commercial part of the ecosystem but also in institutions.”

Two years later, in 2015, she launched 1-54 New York, and in 2018, 1-54 Marrakech in Morocco. She also curates an annual pop-up Fair in Paris. Expanding her reach in major art metropolises with 1-54 supports its mission to raise awareness about galleries and artists from Africa and its diaspora.

This year’s 1-54 New York presented 26 galleries from the U.S., Europe and Africa, exhibiting the work of more than 80 African artists worldwide. Notable artists included Ablade Glover, Mous Lambrabat, Ange Dakouo, Pedro Pires, and Othmane Bangebara, among many others. The power and significance of the Fair is that rather than focusing solely on high-profile creatives, it also establishes a platform for emerging artists to present their work. Her intention to expand the market and support her collaborators’ creativity has proven beneficial to them and the larger market of contemporary art.

“The market is a driver, and that’s a reality,” El Glaoui said. “An interesting example that we had over the years that made a very big influence on collectors and where trends were going was artists like Njideka Akuyili Crosby, for example, who really moved the markets to a different level for Black portraiture and figurative portraiture. That is a reference and example of success in getting to [higher] prices.

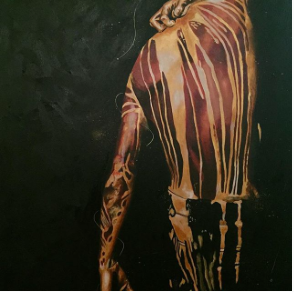

“It led to a huge influence in West African artists going into the Black figurative movement,” she continued. “I think in a couple of years, we will see that moment in time where we had all those Black figurative portraits as a movement, as a moment that is marked in contemporary art history in terms of the Black artists getting into the market. I think that’s very important as well, because it will be defined by this movement of figurative art on the market.

“So for me, you see, I’m coming from a completely different understanding of it because, since 2013, we’ve been showing this, so we didn’t go through a trend or anything; there have been all those artists, and this representation at 1-54, so I was excited about the interest and the sudden enthusiasm about it coming in the last three or four years, but before that, we have had a very large range of artists working with the theme, but also a very large range of artists working with other inspiration and creativity as well. I’m just observing what’s happening right now because I think the collectors are very excited about what they’ve been collecting so far. I think figurative painting has been part of that acquisition over the last ten years,” she said.

“Still, I know that, for example, when we’re working with the collectors now and sharing the list of work that is going to be present at the Fair and the last couple of Fairs, they are going to other things, going to more abstract paintings and that offering is getting bigger engagement as well. I think maybe as general mass consumption, we are moving towards a different direction now as well, and something much more diverse in terms of mediums, inspiration, the focus of those artists and what they’re trying to express as well right now, so I think the interest of the collection is going to be much more diverse than just the figurative arts.”

El Glaoui is a talented curator, but she also works with a selection committee comprised of galleries to determine all exhibited works and partnering galleries. This process is essential not only to assist them in identifying new artists but also to ensure equitable representation.

“So, in terms of the experience of the visitor,” she said, “it’s important for us that they don’t find or have a feeling of ‘I have seen it already.’ Another consideration is to have a balanced number of galleries coming from the African continent, Europe and the U.S. We try to balance that number because we think it’s very important that galleries from the continent have a chance to show at 1-54. We are very conscious about the quality of the galleries, and we also pay attention to what the galleries on the African continent are doing.

“It’s important for us to see the program is beyond the commercial aspect and that they are building an ecosystem for themselves on the continent, because we think it’s very important. We always want to make sure that it is a nicely curated show for the people visiting the Fair.”

Fairs like 1-54, as well as small galleries across Africa, the U.S. and Europe, in collaboration with dedicated curators and enthusiastic collectors, are doing the work to shape contemporary art markets, and by extension, contemporary art discourses. It is impossible to visit any of these fairs and not realize the masterful movements fed by distinct voices elevating conceptions about African artists. Last year marked 1-54’s 10th anniversary. To commemorate, they released a beautiful publication, The 1-54 X 10 Annual Book.

El Glaoui’s work with 1-54 is a tireless effort, a push and pull, a defiance in the face of countless debates attempting to limit African creatives’ impact and significance. The prolific collection of artists and regions that 1-54 exhibits is an essential reflection of the broad talents that Africa produces and the current state and future of inclusive art markets.