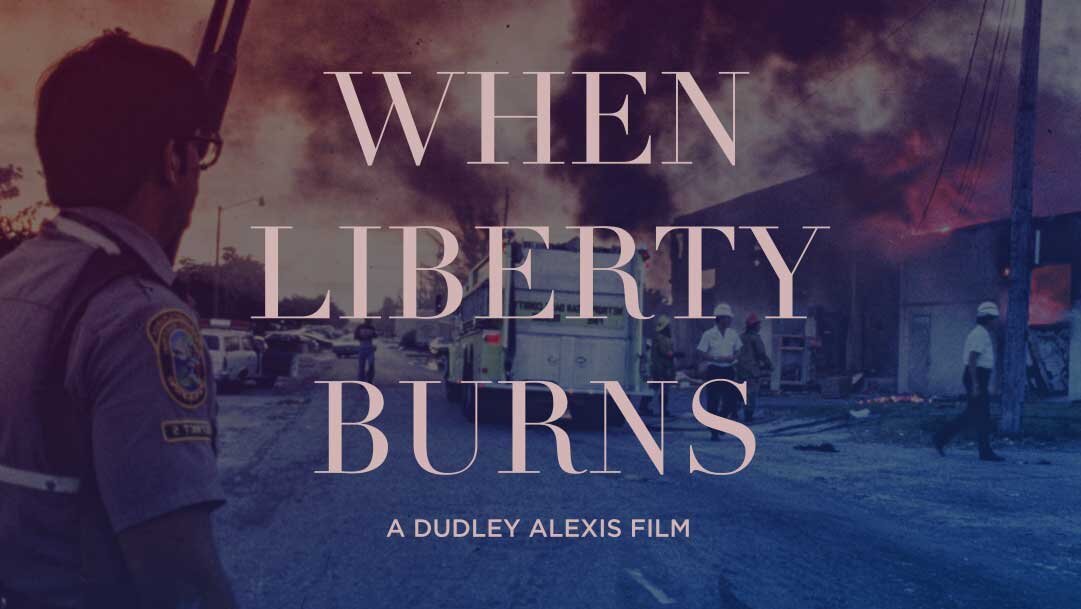

Dudley Alexis is a Haitian American filmmaker based in Miami. His most recent documentary, When Liberty Burns, highlights the life and death of Arthur McDuffie who died after a brutal police beating. The film premiered at the 2020 Miami Film Festival to a sold-out theater. On Juneteenth (June 19, 2020), Miami Film Festival will present an encore online screening of When Liberty Burns, which won the 2020 Knight Made in MIA Feature Film Award for documentary. A week ahead of the screening, I spoke to Alexis about his work, his process, and his inspirations.

April Dobbins (AD): What inspired you to do this particular film? It’s such a tough subject.

Dudley Alexis (DA): One morning I was headed to work and I-95 was blocked. I was really annoyed about the traffic and complaining the whole time. I got to work and found out that someone had been killed by the police on the interstate. When I checked the news story, I saw that the person who died was a friend of mine from high school.

AD: Wow.

DA: Yeah. After that, I learned about the McDuffie case. On December 17, 1979, Arthur McDuffie failed to stop for a traffic light. Police officers gave chase. After realizing he could not escape, McDuffie surrendered, but he was beaten until he lost consciousness. That beating by multiple officers caused his death. In 1980, acquittal of the offending officers sparked the McDuffie Riots, which ultimately changed Miami-Dade County.

AD: Honestly, I didn’t know the details until I saw your film. Everything about the story is eerily familiar. What has changed?

DA: Nothing. You know, in my previous edit, I wanted to include more of the officers’ statements because they were so upsetting, but a lot of my friends told me to just focus more on the McDuffie family. I’m glad I did.

AD: I’m glad too. I want to be sure to cover ground for people who don’t know you, so let’s go back to the beginning. How did you get into filmmaking?

DA: I’ve been doing design, filmmaking, and motion graphics since 10th grade. I studied animation at the Art Institute in Miami, but I really didn’t get along with the people in that department. The students were really insensitive. So, I moved to film. From there, I started working with Micousukee Magazine and became a producer of my own stories.

AD: What were the challenges for you in doing Liberty in a Soup, a film about Haitian independence and the national dish, as a first-time feature filmmaker?

DA: With that first film, I was producing and directing everything myself like a one-man show. People didn’t want to give me their time because they weren’t sure anything would come of the film. The other challenge was that I started filming a few years after the earthquake in Haiti and everyone wanted an earthquake film. Trying to get funding on any other Haitian topic was impossible. That was very frustrating.

AD: Was When Liberty Burns easier to get off the ground as a second feature?

DA: When Liberty Burns had its own challenges. It is based on a case that no one wants to talk about… even today. People in Miami would say, I still have a job here or I work for the city or I have a business, and I want to get those city contracts. They were afraid that saying something would harm their business.

AD: Do you have a day job?

DA: Yes, I do marketing and branding for companies. Most of When Liberty Burns was self-funded, so working during the day helped me get the film done.

AD: The cost of archival footage is prohibitive for most independent filmmakers. How did you manage to use so much in your film?

DA: It is very expensive. The Green Family Foundation came on and helped me a good deal with licensing and some other things. They continue to provide support, which is great. Right now, I have festival rights for the archival footage. I’m hoping to find a distributor willing to help with the cost of full licensing. I’m also going to fundraise.

AD: One of my favorite things in the film is the use of Frederica’s voiceovers. She was Arthur McDuffie’s wife, but we don’t see her on camera.

DA: When I first heard the audio, I thought she had the most beautiful voice. I was determined to make it work visually and emotionally.

AD: I assumed that she was talking to you in an interview, but the voiceover that we hear is actually archival audio?

DA: Yes, that’s right.

AD: The way she talks about Arthur—calling him her beloved, describing her feelings when she first met him—is magical.

DA: I’m glad to hear that. You know when I met her, she didn’t want to be interviewed and neither did the family. They didn’t know me or trust me to do justice to Arthur’s story. I almost cried when I heard that Frederica saw the documentary and loved it.

AD: How did you gain the family’s trust?

DA: I’m not much of a people person. I’m often too blunt, but Femi Folami-Browne, my producer, is great. She was able to convince the family to participate.

AD: How did you find your producer?

DA: She came to one of my screenings of Liberty in a Soup. She would call me every week to check in with me. She had never produced before, but she’s served as a community liaison and activist for years. I told her about When Liberty Burns and she offered to help.

AD: As a Black filmmaker dealing with this type of subject matter, how do you practice self-care?

DA: I was actually planning a trip to Haiti after the film premiered, but then COVID-19 happened. The work does affect me emotionally. There were smear campaigns in newspapers after McDuffie’s death. It was tough reading through everything. Honestly, I would not advise filmmakers to do back-to-back films on such heavy topics. I think my next project has to be something fun. Just for balance.

AD: Social issue films can be emotionally exhausting.

DA: I don’t know how Ava DuVernay does it. She goes from one heavy film to another, and she’s still active on Twitter. I’m like, those therapist bills must be crazy [laughs]. I’m just kidding.

AD: What do you think your next film will be?

DA: Well, I do want to do a project that tackles racism in modern Miami.

AD: You just said that you want to do a fun documentary next… like, seconds ago!

DA: I know. I know. There are a lot of interesting demographics in Miami that you don’t find elsewhere. I want to explore how Cuban Americans feel about racism and Black movements. I also want to do a film on Toussaint Louverture.

AD: Do you have any interest in doing narrative film?

DA: I do, but my biggest struggle is finding a script. I am not a screenwriter. I have a friend who is writing a script for me now.

AD: Anything else we didn’t cover?

DA: You know one last thing I wanted to mention—when I was interviewing people for When Liberty Burns, after almost every question, I had to stop so they could collect themselves. They would cry at the mention of Arthur’s name. They shared 40 years of pain with me. That was the toughest part.

AD: Yeah, you can feel that. There hasn’t been a space for true healing. There are so many different perspectives of Arthur McDuffie. He has a whole community of people who loved him—who still love him.

DA: Exactly. People really looked up to Arthur. He made an impact and people trusted him. I tried my best to tell the story of his life by examining Miami’s history and his relationship to the city.

April Dobbins is a writer and filmmaker based in Miami. Her work has appeared in a number of publications, including the Miami New Times, Philadelphia City Paper, and Harvard University’s Transition magazine. Her films have been supported by the Sundance Institute, International Documentary Association, Firelight Media, ITVS, Fork Films, Oolite Arts, and the Southern Documentary Fund.