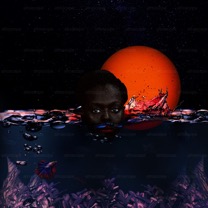

Above: We Float In The Cosmos With Amun-Ra, Digital Collage, Photoshop , 24” x 24”

“For me, it’s a way of looking at the future, looking at alternate realities with an Afrocentric perspective or point of view. Where our imagination as people of African descent and Black people are held up as important. We also have a claim on the future, and our stories about what this future could be or other realities look like matter. Afrofuturism becomes a platform that allows for these perspectives to thrive and be shared,” relates Nana Opoku, artist and mind behind the world of Afroscope.

A Swarthmore College graduate with a B.S. in statistics and economics, Opoku did not initially embrace the Afrofuturist label that his audience, particularly on Instagram was placing on his work. Like many artists, Opoku’s pieces began as experimentation without a focus. A combination of both his growing consumption of Afrocentric material, as well as remarks from those engaging with his work, led to what would be named Afroscope.

Portrait photography and photo manipulation technology including Illustrator, Photoshop, and Pixel Maker are the primary tools Opoku uses to bring Afroscope to life. Using mostly his own photographs and sometimes stock photography images, he employs photomanipulation technology to embark on an exploration with no intended destination.

“I’ll take a picture that I like or a photo that I took a couple years ago and say, ‘lemme make something with it.’ And sometimes, I don’t really take the photo and turn it into anything besides a slightly edited version of the original. Sometimes, I completely pick it apart and transform or transport the object or the people into another world.”

He tells me more than once, “There isn’t a defined approach.” It is difficult for him to pin down his process, as he is guided by the intention to explore. Although there is no game plan for what the end product will be, each time the artist employs his vehicles, he is transported to unexplored dimensions. It is the transportation from one reality to another that makes Afroscope so captivating.

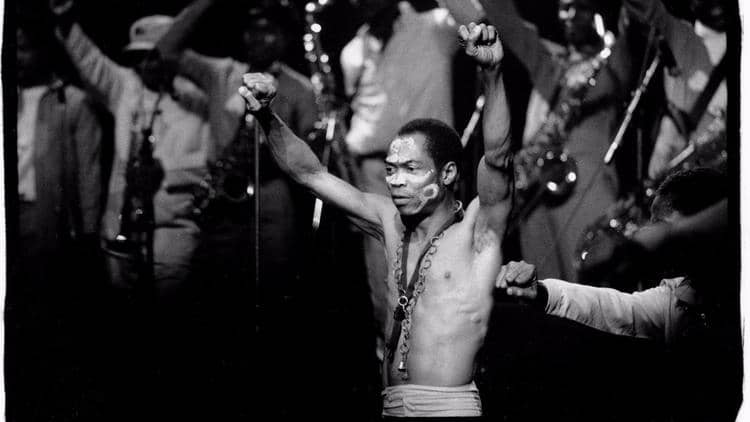

Opoku credits digital capabilities with driving him to worlds that feel like our own, yet are also unreal. When asked how the worlds of Afroscope are different and similar to our own, he explains that his work evokes the concept of Shamanism.

“Shamans are sacred beings/priests who are able to enter altered states of reality to tap into some version of this world or other world to help other people with some spiritual problem or some ailment or some questions that they have,” Opoku says. “They are here presently but tapping into another dimension, another reality. And in a way, that intermediation happens with digital technology.”

Opoku can be seen as a Shaman communicating an important message to the Diaspora through his work. In these alternate realities, African descendants exist in a position of empowerment that is difficult to recognize in our current reality

Throughout the world of Afroscope, space, the sky, orbs, planets, and moons are ever present. Opoku explains that this is his way of incorporating the concept of samsara or the idea that in this existence, there is a recurring circle of life and death, a continuous wheel.

“Those ideas find their way into my work because they naturally speak to people about the beyond,” he says. “They naturally connect with this idea that we are connected to the earth and the planets and space. I try to make those connections apparent by juxtaposing people with nature and with space. We are connected to all these things no matter how distant they may seem.”

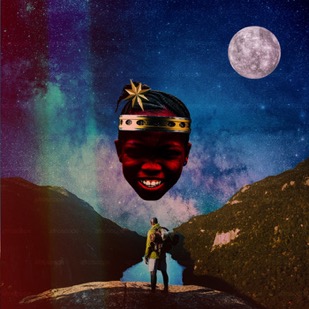

Just as essential as celestial forms are to Afroscope, so are human-like figures. In a work like The Last Laugh, there are no unrecognizable forms, but their placement gives the image a dreamlike quality. The smiling face of a young girl rests suspended in the center against a starry night sky, the aurora borealis coloring the horizon, a full moon glowing in the upper corner.

In the foreground, a hiker looks to a downriver valley, but it might be assumed he stares at the planet-sized face above. The juxtaposition attempts an interpretation around gaze and subject. After all, the girl looks in—toward us, or the hiker—as the hiker looks out. In either case, the girl’s face is the power in and of this photo. She is a celestial body and of a world of her own looked upon in wonder.

Many of Opoku’s human-esque subjects have god-like and animal-like qualities simultaneously. Some possess necks giraffe-like in proportion. Others have beams of light pouring from their eyes. A woman with her head split in two reveals divine light emanating from within. With titles like Guided By The Light of Ancestral Insight and Looking to Rah for Spiritual Guidance and Redemption And Salvation From The Onlooking Past, these images call on Africans to embrace a history and tradition that have been neglected in the quest to embrace all things Western.

“I lean towards the suggestion that a lot of our past can be a guide or pathway towards a brighter future,” explains Opoku when asked how Africa’s past and future are conceptualized in his work. “I try to use my work and the work I’ve completed to shift the gaze a bit towards our ancient knowledge systems, writing systems, and oral histories that have been left behind.”

Although Afrocentrism, Afrofuturism, Shamanism, and samsara are the predominant concepts molding Afroscope, Opoku is careful to relate that the fruits of his experimentation are very organic. What began as a journey without a destination became a reflection of what the artist has consumed as well as what interests him. In mourning the abandonment of African tradition as well as contemplating future technologies and artificial intelligence, Opoku brings us figures that hold the power of the past and the power of the future within.

“A lot of the time, the gazes from people’s eyes, the god-like aura that they have is an ode to our ancestral past already knowing that we have what the West is now counting as AI and the power that it has. When we look at what has come before and what is here now, rather than thinking that we have to wait for someone to bring salvation, just recognizing the self-efficacy in ourselves. Really seeing the future within ourselves,” Opoku says.

“That visual of beams flowing out of the eyes, it’s a very strong form of imagery to suggest some of these ideas which can be elusive. We are these god-like beings. We don’t recognize that within ourselves on the day-to-day. To me, it’s unfortunate. If my work can awaken that spirit in someone, especially someone who’s part of the diaspora, for them to feel like, yo I can change the world. I can see a new future. And that future matters, let me make that happen or let me at least try and I’ll achieve something.”

Nana Opoku resides in Accra, Ghana. He is the founder and CEO of House of Stole, which makes kente stoles for graduating students of African descent. In addition to receiving the 2017 Kuenyehia Prize for Contemporary Ghanaian Art, Opoku’s work has been part of multiple exhibitions in the Accra area, including Diaspora: From Local to Foreign, an art exhibition created as part of the 2019 Year of Return Event. Opoku’s work will be shown in the A.I. For Afrika’s art entry as part of the upcoming A.I. For Good Global Summit taking place in Geneva in September 2020.