Black skin and hair are inescapable icons and unique identifiers that have been reclaimed as a source of pride, aesthetic joy, and cultural capital throughout the diaspora.

When property, safety, and even life are cut carelessly from Black people, hairstyles can represent safety. The impact of hair at 1-54, May 8-11, in New York City, wasn’t lost among the choir of African artists’ voices. It was loudest from Joseph Eze (Nigeria) at Dozie Arts gallery, Taiye Idahor (Nigeria) at O’DA Art Gallery, and Marc Padeu (Cameroon) at Larkin Durey gallery. Between abstraction and figurative works, hair was a quiet element that grew to a subject level and even a full-on character in some works because of how it was articulated.

Skin and hair are foundational to Black identity. From dehumanizing Black people in chattel slavery and casting Black skin and hair as slave-class markers globally, they became points of ridicule for non-Black people. Black skin and hair are inescapable icons and unique identifiers that have been reclaimed as a source of pride, aesthetic joy, and cultural capital throughout the diaspora.

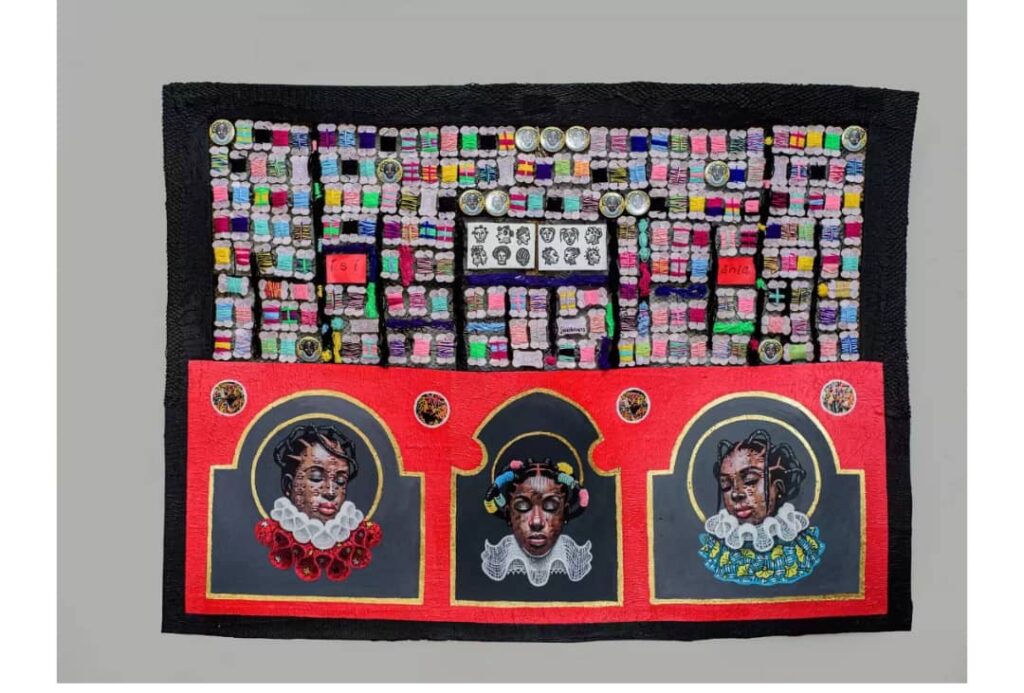

Joseph Eze’s series enshrines how hair and fashion are steeped in culture. The regal red backgrounds hold Black women’s faces and thread spools. His works allude to the hairstyle of Isi Òwú traditions that are features of his characters.

By including threads in his works, he stays in trend with fiber art’s popularity. Even in the space of his paintings, Eze displays an acute attention to detail when rendering fibers. This same attention is showcased when he uses a double-exposed layering of faces in the skin of his characters to conjure a familial and ancestral connection with Black skin.

Over his mark-making, he derives significance from the hair itself. He paints hair that represents the Igbo “Isi Òwú” tradition. By juxtaposing Victorian fashion and Nigerian hair traditions, he braids together cultures that clashed because of European imperialism.

Socially and culturally, hairstyles represent relationship status, age and symbolic rites of passage. For centuries, Isi Òwú has carried social and aesthetic significance in Igbo culture. Isi Òwú is worn by young unmarried women, who show their youthfulness by wrapping their hair with black threads.

Black hair is deeply politicized. As recently as 2024, the Supreme Court upheld the indefinite suspension of a Texas high school student, Darryl George, for the length of his locs. This decision occurred even though the CROWN Act (Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair) of 2019, which was enacted to prohibit K-12 race-based discrimination in California, has been passed in around 25 states.

Without words, Black hair represents cultural vitality. It’s how, with words, songs like Don’t Touch My Hair by Solange Knowles, How To (hair) by Esperanza Spalding and even Willow Smith’s pop hit I Whip My Hair embrace cultural language that transcends the moment. We care about hair.

Collage elements, which borrow photos from salon hair posters, are used for reflection in Taiye Idahor’s series Wade In the Water. Faces and hairstyles meet to float in the braid-patterned ink prints, acrylic and oil pastels that fill her canvases. The photos in The clouds roll back, Asking for directions and Peace like a river are trophies of idyllic representation that show women treading safely in identity and culture.

Salon hair posters offer a way for people to see themselves, finding agency through stylistic expression. Beyond aesthetics, salons and barbershops often serve as safe havens within Black communities. The wave-shaped hairstyles featured in these posters are carefully curated in corners and shopping centers across the states, symbolizing both cultural pride and sanctuary.

By referencing a culturally rich cove of symbols and imagery, the images in the collage represent the entrenched relationship of Black iconography and respectability politics. Our union in the diaspora is quiet language that makes waves. It’s how we create ways to survive and thrive together in murky political waters.

Another series Idahor showed at 1-54, Emancipated but not free, shows simple gestures bogged down by loads of tangled hair. There seems to be a stark contrast between the open field and gesture in I Was up…, where, without her hair concealing her frame and movements, she would be naked and likely free to move. This relationship with hair seems to point to the parallels that hair has with respectability among the social pressures of being Black, despite the ways in which it can be a source of resilience.

It would be remiss not to mention how Black women endure worse hair-based discrimination compared to men. According to a 2023 CROWN Act Research Study, Black women’s hair is 2.5 times more likely to be seen as unprofessional. This bias results in Black women with tightly curled hair being two times more likely to experience microaggressions at work if their hair isn’t straight.

Hair helps humble, hide, elevate and communicate personality. It’s a crowning icon. Series like Idahor’s make clear that hair respectability and discrimination have scalp-deep, traumatic roots in the diaspora.

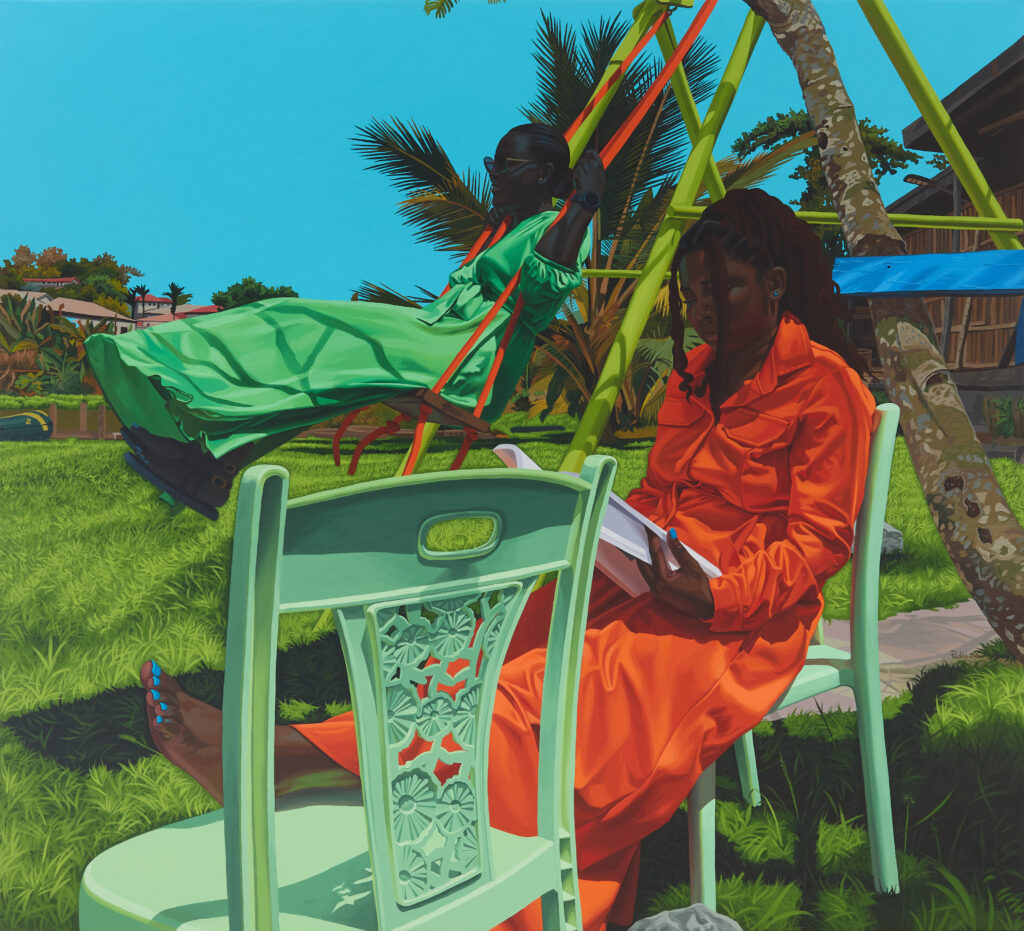

Marc Padeu renders hyperreal hair touched by light like a spritz of water. His pieces are hair follicles that cover the diaspora’s scalp and require those who, with dextrous fingers, speak the language of fine art to use it as a protective style. Padeu does so by highlighting Black ease and joy with hyper-realistic detail in pieces like La Balançoire 1 and La Balançoire 2. Padeu’s work depicts moments of repose. Tender qualities in mundanity are communicated by the delicate mark-making of these buttery pieces.

The way he makes marks on fabrics is appropriately airy. The way he renders organic materials like wood, plastic chairs and tiles is dry and grounded without feeling stale. The way he presses his brushes on canvas, which bleed oil when painting locs, bears a tender style saturated with a cultural understanding of hair’s significance.

One of his works, not on exhibition at 1-54, Les Murmures du Festi, uses scalps like torches to carry the light found in informal intimacy.

Wading in turbulent expectations, Black people are surrounded by respectability like liquid lead. The cultural waters allude to a language of survival, which is safe because they’re familiar in the diaspora. The unavoidable relationship between Black hair, societal pressure and respectability makes them an integral part of the Black experience.