Above: Aaron Douglas, The Negro in African Setting.

So where does African American art end and African diaspora art begin … For me, the space between ”African American” and “African diaspora” is not a matter of division or disagreement, it’s a matter of accentuating the encounter—the space is where we must meet one another and choose to have the capacity for understanding rather than opposition (Page 63).

Does the rubric of ”African American” begin to have colonizing aspects? (Page 2).

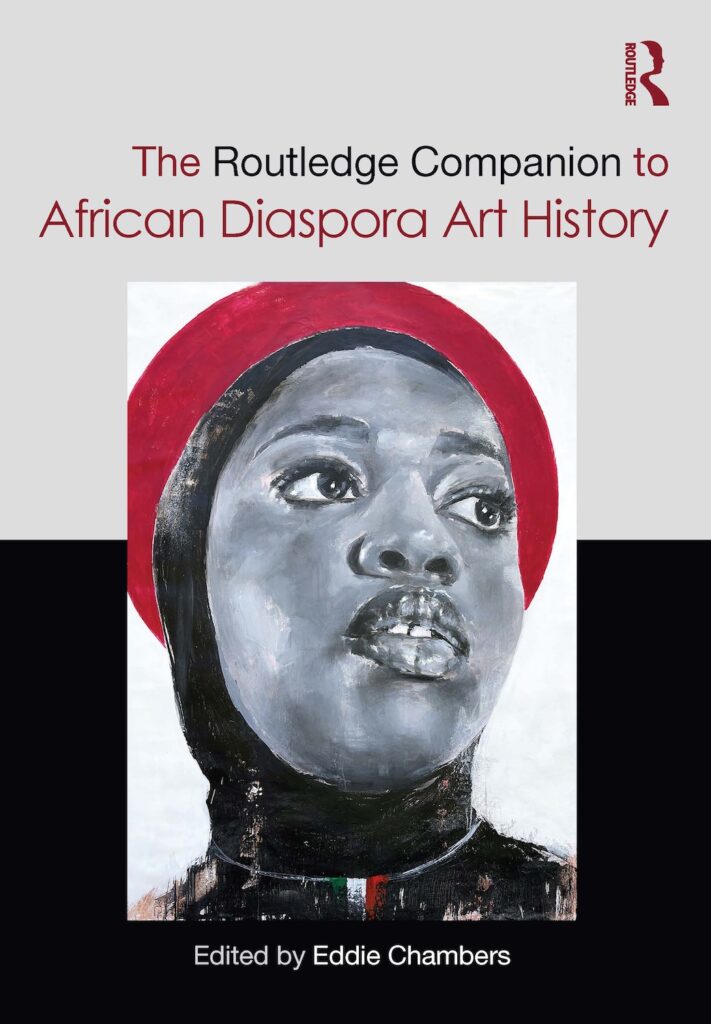

My first reaction to The Routledge Companion to African Diaspora Art, edited by Eddie Chambers, was, “Wow, I’ve succumbed to this fallacy: calling someone African American when they were not while teaching about Black art.” But I’m not the first and likely not the last to think this way. Our perceptions are rooted in the limitations of language, those terms, and the discipline of art history.

What is unique about this four-part anthology is that it is edited by a Black British artist who was very involved in the Black arts movement in England in the ‘60s and ‘70s. There’s an echo within all of the various essays by scholars like Jacques Derrida (who, I forgot until this moment, was born in such a charged environment as Algiers), Krista Thompson, Kobena Mercer, Stuart Hall, Édouard Glissant, Okuwi Enwezor and many more. These theorists are held next to artist-theorists in many names new to me, like Kowokan, El Loko, Maud Sutter, Freddy Tsimba, Herbert Gentry, Ernest Mancoba, Isabelle Winfield and Marton Robinson.

There are many intersections that showcase the slippage between two terms: African American and African diaspora. One of them being the one-drop rule that quantifies someone for being Black in America, but they could be of African descent or part of the diaspora at large. For example, Marcus Garvey, the leader of the UNIA (United Negro Improvement Association), was from the West Indies, although he had considerable influence on Black Americans / African Americans. Another intersection with slippage is Haitian independence, which appears in the works of Jacob Lawrence, Lois Mailou Jones, and other artists because Haitian independence becomes emblematic of self-emancipation and maroonage of Black peoples.

On the flip side, it’s important to receive the reminder that one rarely stays in one place—William H. Johnson spent considerable time in and lived in Scandinavia, and many Americans lived in Rome and Paris (e.g., Edmonia Lewis, James Baldwin, Beauford Delaney, etc.).

Since these terms are slippery, this anthology questions what a diaspora is, what it is in an African context, and whether this term is inclusive or exclusive. Some essays posit that Asians in East Africa are part of the African diaspora or that people from the Maghreb part of this area are as well as are even settlers (a word privileged over the term white to honor Indigenous theory) in Africa (like white South Africans).

The book also asks, “Where does Caribbean art end and Latine art begin?” While Latine refers to Spanish-speaking people, it in itself is not a geographic place, while it is often referred to as such. The distinction between the two terms is often one that is made because of anti-Blackness: Afro-Latine must be a prefix to indicate Black. It’s othering and hegemonic.

At one point in the book, diaspora is challenged or interrogated because the original meaning of the word is rooted in Zionism, and it holds the history of a Jewish context. It refers to a scattering of seeds in its etymology. Whether this word even serves an African context is what the author and scholar Stuart Hall grapples with. How do we linguistically unite while this settler-colonial term entraps?

“Similarly, Stuart Hall called for a definition of diaspora identities based not on a notion of an original homeland but rather on hybridity. Diaspora identities are those which are constantly producing and reproducing themselves anew, through transformation and difference.” Later on, he writes, “Philosopher Edouard Glissant has taken the view of diasporic being as a revolt against the epistemic violence of the French language, describing diasporic being as ‘being Outside of language.’”

However, essayist Yasmine Espert has a powerful and necessary assertion. She writes, “I argue, however, that writers, curators and artists don’t have the luxury to wait for academic institutions to create or approve theories containing Black life. We are creating theory while we do the delicate work of listening, interviewing, exhibiting and documenting.” (Page 65).

The benefit of having this book in my collection is having the luxury of returning to these artists and essays. It accompanies other textbook-like books that I own and recommend, including Crafted Kinship by Malene Barnett, African American Art by Lisa Farrington, Surrealism and Us by Maria Elena Ortiz, Simone Leigh monograph produced by the ICA as well as the Sovereignty brochure, and Commonwealth: Art by African Americans at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. I’m excited to hear the polyphony of these books together.