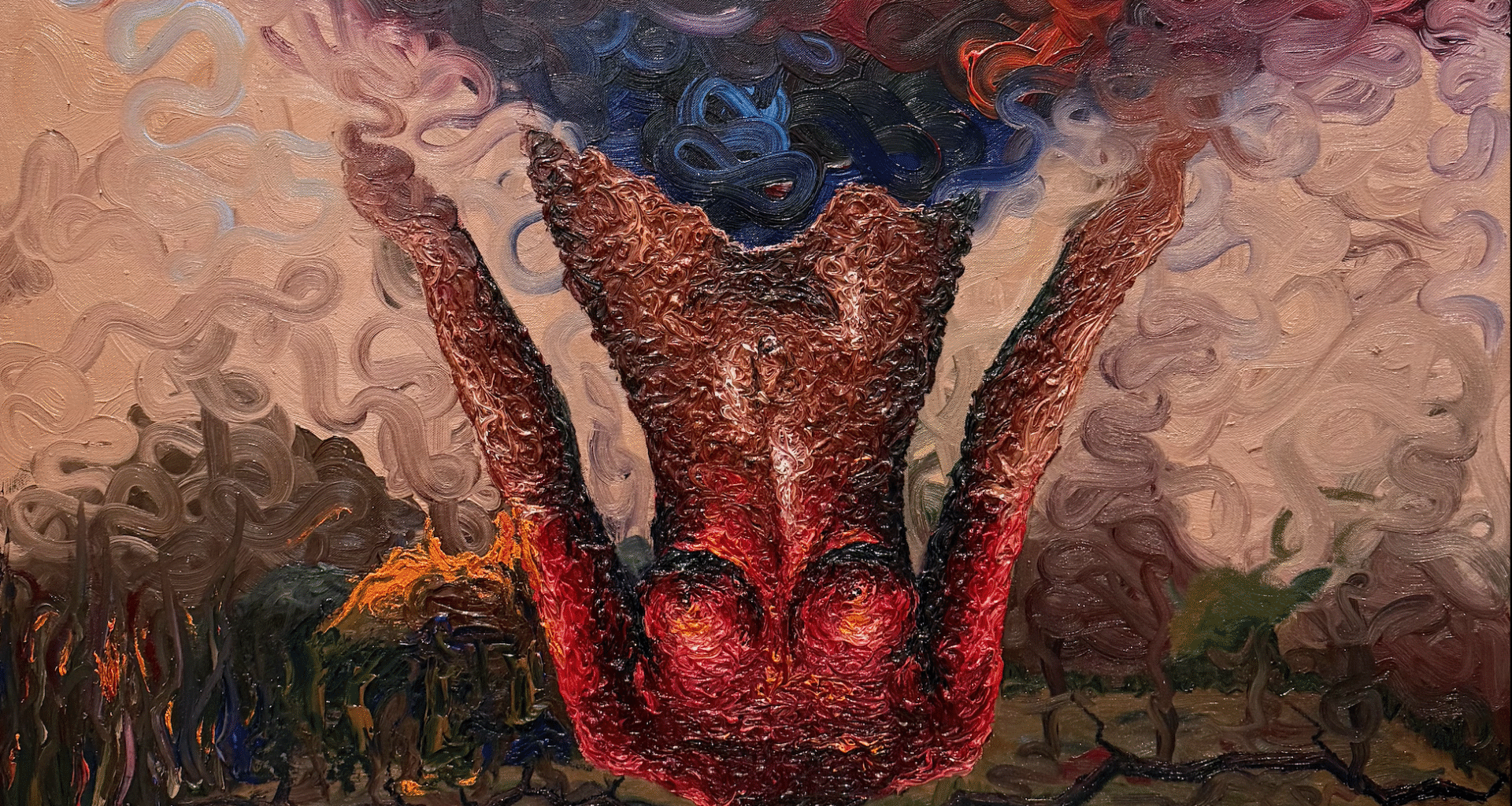

Above: Steffani Jemison , WLD (content aware), 2018 UV curable inkjet print on glass, acrylic, paper, polyester film10 x 21 1/2 in.Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

We are a generation that consumes more media than any previous generation but is less equipped to decipher the barrage of content that we receive. Every day, we are inundated by countless communications: the advertisements that interrupt our commutes or doomscrolling, the slant of trending memes, and a litany of other targeted transmissions, most subliminal in nature, encouraging our passive consumption.

How do we consciously and actively work against a passive relation to language? How do we review new ways of reading in support of our healthy being and informed futures? What conceptual, creative, and theoretical interventions already have been deployed to elicit an elucidative rather than sedative relation to language?

Scrawlspace, a new group exhibition curated by Emily Alesandrini and Lucia Olubunmi R. Momoh at The Shelly & Donald Rubin Foundation, The 8th Floor gallery, presents a robust selection of works by artists of the African diaspora who toe the line between abstract and representational forms by privileging text, writing, and language. Featured artists include Sadie Barnette, Lukaza Branfan-Verissimo, Sonya Clark, Tony Cokes, Renee Gladman, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Steffani Jemison, Glenn Ligon, Adam Pendleton, Jamilah Sabur, Gary Simmons and Shinique Smith.

Upon entering the intimate 8th Floor gallery, you are greeted by familiar and undecipherable language, distinct mark-making, redacted and abstracted texts, assemblage and history-laden codex, as well as banners and murals with clear and urgent liberatory proclamations. Each work queries the ways we have learned to make meaning from language and create new language as necessary when what existed was not enough.

Many of the works reflect troubled histories of intentional obfuscation and attempt to reorient our perspective in honor of the potency of fugitivity. The exhibition includes many iconic artists and notable works that are rarely displayed. Momoh was kind enough to guide me through the exhibition. We spoke at length about how artists engaged with critiquing and revising language illuminate cogent discourses about the conditions of our time. I asked about the impetus for the show.

“I think Emily and I were talking a few years ago about how there were a lot of artists looking to the written word,” Momoh said. “She had seen the FBI Drawings series by Sadie Barnett. We were both really big fans of Glenn Ligon and his practice. Emily works a lot with opacity. I study portraiture in the 19th century and the historiography of representations of Black and Indigenous folk in history and within museums. So, we were both critical of not just the primacy given to the figure writ large within representations of POC in institutions but also the fact that I am personally very wary of the language that surrounds these images.”

Over the last three years, Momoh and Alesandrini have been thinking about these themes, mining the history of visual culture to unearth artists whose practice and process analyze the construction, deconstruction and interpretation of language in relation to the lives and histories of Black people. As an interrogation of language, particularly as it is invoked within Momoh and Alesandrini’s curatorial project, Scrawlspace reviews and contributes to Black liberatory cultural and canonical traditions that value queer, intersectional, and decolonized research, writing and visual praxis.

The term also is bound indelibly to Black post-colonial and post-structuralist theorists. Fred Moten credits poet and scholar Harryette Mullen with coining the term, who further positions Hortense Spillers as the progenitor of the term. By activating the term as a rallying apparatus that culls histories of radical visual praxis absorbed by the possibility and precarity of language, Momoh and Alesandrini present a brilliant, sometimes overwhelming, but undeniably inspiring exhibition.

“What I love about artists who are investigating words, which are another element of representation because the combination of image and text was essential for constructing race and constructing hierarchies,” Momoh explained, “is that without the body present, we can think about how race is reified by language, how hierarchies are reified by language, how race is also connected to the environment, to practices of excessive extraction, and also how language offers a portal through which we can explore.”

We have been taught that written language indicates civilization and that cultures that leveraged transcribed histories over oral traditions were more advanced. This troubling conception has poisoned all disciplines globally by discounting the merit of differing relations to chronicling the passage of time.

Scrawlspace incites audiences to expand the ways they approach legibility. More often than not, when presented with the artists’ representations of language, our linear, left-to-right interaction flatlines, prompting a connection to ancient comprehension modes that defy colonized language codifications. In this way, gestural mark-making that cites, remixes and repeats Black language also mirrors dialectical practices of call and response, signifying, ceremonial possession and maroon subterfuge. At all times, the works on display complicate our collective engagement with language, bringing an energized awareness to language that diverges from subliminal passivity.

While processing these ideas, I thought a lot about Zora Neale Hurston’s timeless essay, The Characteristics of Negro Expression (1934). The urgency of her notions, relating the expressive nature of Black language to cultural and behavioral patterns retained despite colonization, became more evident for me while moving through the space. I marveled at each artist’s conceptual and aesthetic intricacy and found a greater appreciation for the profoundly compelling corollaries between multidisciplinary and multigenerational practices that Momoh and Alesandrini reviewed.

“All of these artists are really creating and investigating words towards liberatory means.” Momoh continued. “There is a lot of writing against writing, through and back to, but I feel like everything is also a writing towards liberation. I love to think of sentences, syntax and words as functioning like a sponge that holds so much potential. There’s a cleansing element there, too.”

Artists have always played a pivotal role in our collective construction and deconstruction of reality. There is an eloquence to discordant indecipherability. So, too, can distortion catalyze clarity. Scrawlspace swoons in the emancipatory potency of Black lexicons. By elevating the efforts of artists working through text, script and prose, we expand our relation to space-time, become more critical in our assessment of text as incontestable historical proof, and more persistent about evidencing the creative interventions that prolifically resist erasure, reduction, redaction and misinterpretation.

Scrawlspace is a genuinely generative exhibition that lends itself to the ongoing repositioning, reconstruction and reinterpretation of past, present and future language.