Wood’s work tickles a polarizing tightrope and imbues a futurist lens that looks at several ways Black femininity takes shape in the American zeitgeist.

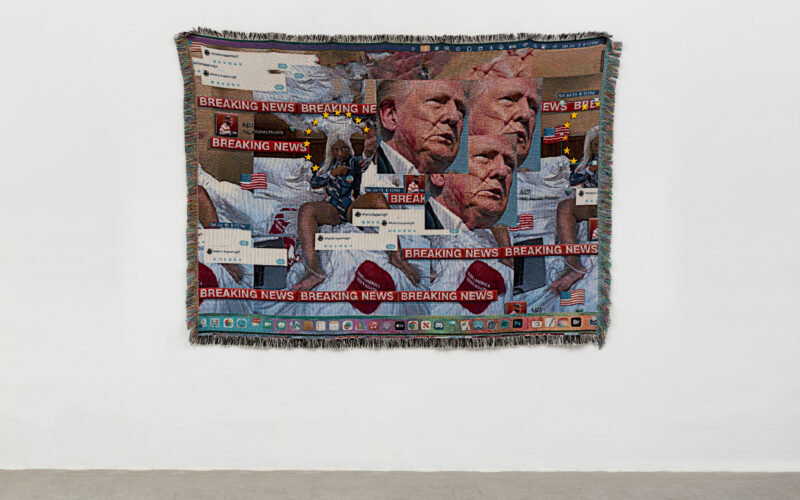

Above: Qualeasha Wood, This is America, Season 248, Episode 45, 2024, woven jacquard, glass seed beads and machine embroidery, 136 x 186 cm, 53 ½ x 73 ¼ in. Courtesy of the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London. © Qualeasha Wood 2024. Photography by Ian Byers-Gamber.

Qualeasha Wood enters the contemporary art conversation as an interdisciplinary Black femme who balances analog and digital techniques in her practice. Her pieces use a digital-visual language with analog and technological motifs to explore contemporary Black femme ontology. The dialogue in her works is controversial in the imperial core, so she showed her work at the 30th Annual Armory Show in New York with the London-based Pippy Houldsworth Gallery to distance her pieces from hyper-critique in an American landscape.

Wood is a Jersey girl at heart. Between 2019 and 2021, she studied fine art and printmaking at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence, R.I., then fine art and photography at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield, Mich. Fine art academia helped her develop interdisciplinary craft skills. Still, her voice is steeped in lived experiences of being a Black femme in metropolitan cultures from New Jersey and New York to Detroit and Philadelphia, where she currently works. Wood’s work has traveled a lot, too.

“The work exists at that intersection between technology and textiles,” the director of Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, Georgia Lurie said. “She works in jacquard tapestry. Jacquard looms were actually the kind of early template for computing. It’s kind of like each stitch is a pixel.

“The tapestries are current. Her tufted works have a more retrospective quality, and they’re looking at imagery from cartoons that she grew up watching that are overtly racist but thinking about girlhood and memory within that.”

Wood’s work weaves in memory and identity by using jacquard. She continues the practice of Black woman textile artists among greats like Faith Ringgold, Bisa Butler and Karen Hampton. By practicing jacquard weaving, the predecessor of modern-day computers, she adds a technological layer to her sociologically present pieces and establishes herself as a contemporary design vanguard.

Wood’s work showcases “glitch feminism”—a socio-techno relationship with gender and sexuality. “Glitch feminism” was coined by Russell Legacy in 2013 and looks at how a perceived “error” in a sick society can be a potential correction. Marginalized artists and theorists’ work and critiques of imperialist oppression tools—sexism, racism and classism, among others—can be the lens through which people see a more equitable world.

Her tapestry decorates public collections at the Art Institute of Chicago, The MET, The Museum of Fine Art in Houston and the RISD Museum. At the Armory Show this year, Wood presented works responding to the first Donald Trump assassination attempt in July. Her piece This is America, Season 248, Episode 45 weaves images of Donald Trump post-shooting, tweet screenshots, “Make America Great Again” hats and a seeming costume of Black woman Republicanism.

Many of her pieces include self-portraits. Wood pushes the envelope by reflecting on how she embodies a nuance of Black femininity. Her work tickles a polarizing tightrope and imbues a futurist lens that looks at several ways Black femininity takes shape in the American zeitgeist.

We discussed the intersections of her work:

Lilac Burrell: Your work blends obsolete digital design archetypes with ethereal self-portraiture. I feel like it highlights a reflection of youth being a part of a world that never really existed. Does any of that resonate with your practice?

Qualeasha Wood: When I went to art school, I originally went for illustration, realized I hated drawing the way that it’s taught, and ended up getting into printmaking. I just fell in love with the process. I started working with images as a way of archiving and working with images of the self, because you own exclusive rights to, or you should own exclusive rights to your own identity, and your own image. Like, yeah, we should. We don’t anymore.

LB: We definitely don’t anymore. That’s a conversation.

QW: Especially for marginalized folks, there is no safety net in making only digital work in digital spaces. To a lot of people, for me, I’m like, “I’m creating this thing that doesn’t exist.” And for other people, it stops at it doesn’t exist. I started textiles because I was in printmaking. I started making prints and doing all those things, and none of them felt impactful. What ended up resonating with me was just like my own family’s relationship to understanding art, which ultimately, for them, was always through textiles. Textiles have that long-standing history in fine art and jacquard weaving, and woven images definitely have that long side, long-standing history. So, I started to make these large-scale works that were there to take up space and then to reinforce an idea into fact.

LB: What does it mean for your art to be represented by Pippy Houldsworth?

QW: When I realized there was an opportunity for the work to be international, that was, like, really deep. I feel like she puts a lot at risk, and I think she’s always been really interested in showing Black art, like showing Woody De Othello’s work, and showing Faith Ringgold’s work, and working with Ming Smith and then now working with me and Nengi Omuku. I felt like going there didn’t feel like exploitation. I think it was great to come into working with Pippy and not feel like I was fulfilling a quota. It was also challenging because, being a Black American, making work about race in America is so different than making work about race in the U.K., because the way that race is talked about in the U.K. is vastly different than how we are discussing it here. And so, I think I tried to learn to have more conversations in my work and try to reach a broader audience.

LB: How does your tapestry embolden your audience’s relationship with authenticity between the physical and digital world?

QW: I like to say that I make work that provokes a conversation or prompts something. For some people, I introduce a conversation and a validation for other people. I introduce a confrontation of the self. My favorite thing to do, what I do a lot of, is I go to shows that I’m in, and I stand there, and I listen to people talk about the work, like, I’m in there with shades on. And sometimes, I do my best to not interject. There are times where I will interject in people’s conversations. I think, in general, art is to be projected onto. For me, I’m making work that is so much about me that it does the other thing right, where it comes back on the other side and becomes a collective feeling, or a collective response, or a collective mood. I think that’s what it should do. I’ve never wanted to make a generalization of how all Black people, women or queer people have to feel about a thing. I’ve always wanted to open the space and then see what adjustments have to be made from that.