How do we navigate the struggles of our interior worlds while also grappling with the socio-cultural and economic politics that shape the societies we live in? This question animates much of my engagement with the exhibition “And I Resumed the Struggle”, considering the interplay between intimate space and public spheres, intertwined connections that too often are unacknowledged. The exhibition is currently on view at The Olympia Gallery in Kingston, Jamaica and is the third iteration in a series curated by artists Philip Thomas and Camille Chedda. The show features work from newer and more established Jamaican artists, fostering an intergenerational artistic dialogue, and includes Greg Bailey, Kimani Beckford, John Campbell, Camille Chedda, Shediene Fletcher, Xayvier Haughton, Trishaunna Henry, Sasha-Kay Hinds, Tevin Lewis, Prudence Lovell, Petrona Morrison, Sharon Norwood, Brad Pinnock, Omari Ra, Oneika Russell and Philip Thomas. It is refreshing to see an exhibition curated by artists, who usually prioritize nurturing the work of the other artists involved.

“And I Resumed the Struggle” as a series began in 2020, in part as a response to impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and served as an opportunity for the artists involved to share their work at a moment when many felt exhausted from social disconnection. The artists grapple with questions of power amidst the ongoing pandemic, interrogating geographic, racial, and economic inequities, climate change and its effects on the Caribbean, and experiences of emotional friction. With insufficient governmental funding geared towards supporting the visual arts and so few spaces that highlight the work of contemporary artists, the exhibition provides a much-needed window into the range of vibrant artistic life that must be nurtured in Jamaica.

Above: Tevin Lewis | It’s Always Sunny Tomorrow with Fossil Bites and Monosementa | mixed media | Size Variable | 2021.

.

The gallery is part of the historic Olympia residential complex, built in the mid-70’s and the brainchild of civil engineer A.D. Scott. One of the most architecturally distinct buildings in Jamaica, the octagonal complex rises three stories, with a mural by famed painter Barrington Watson spanning the third floor and an intricately designed plexi-glass domed roof. The exhibit showcases work across a range of mediums, including painting, installation, photography, and textile. One of the first pieces I encounter in the gallery is Xayvier Haughton’s mixed-media triptych, The Visualization of Carbon Series. Haughton incorporates cow hide into each portrait, bordered by formations of nails hammered into the wooden frames. Oneika Russell’s Myth series hang alongside, digitally printed beaded tapestries that meditate on notions of Caribbean identity. My eyes follow the detailed markings mapped onto the fabric, each layered with imagery of ecological life. Russel manifests a feeling of wandering through her manipulation of the textile that is both cohesive in texture and color.

Above: Brad Pinnock | Race Apocalypse | Mixed media collage on paper, wooden chair | 96 x51.5 inches | 2021.

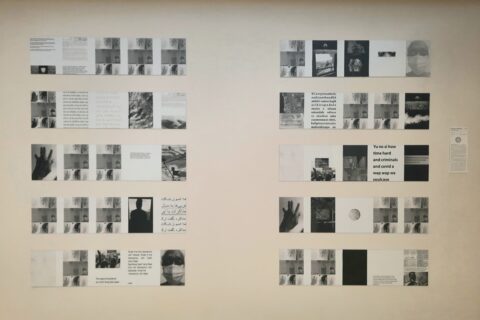

Petrona Morrison’s striking gaze stares back at me in Absence III, engendering a wave of isolation. For a moment I am transported outside the expansive gallery into a solitary space, recalling blurred days during the pandemic when the only company I saw was my reflection. Morrison’s collages register emotionally, piercing into the interior self through quiet simplicity. It sets a somber mood to witness her next set of collages, Covid Diaries I and II, which bring together multi-language texts, scenes of social upheaval, aerial views of varying landscapes, images of Morrison’s face with a surgical mask and repeated photos of her hands. The digital collages, direct without being didactic, ruminate on the psycho-social effects of the pandemic that exacerbate inequities, which have always disproportionately impacted countries in the Global South. The repetition of photos and consistent use of black and white balance the magnitude of the imagery.

The proximate positioning of works by Russell, Morrison and Hinds evokes the most thoughtful conceptual connection made throughout the exhibition. In 1.22 22 a photo of Sasha-Kay Hinds is imposed onto a found image of bare breasts with the markings made during a plastic surgery consultation. Hinds’ eyes are redacted with a white rectangle, denying access to the viewer. Other photos in the series display an exposed stomach, along with two self-portraits, eyes both confronting the camera and turned downward. A defiance resonates in the vulnerability of the photographs, demanding the viewer reckon with their preconceived notions of beauty, desire, and the violence so often projected onto the bodies of Black womxn.

While I appreciate the cynical tone of Omari Ra’s work as a chance to think critically about the residues of coloniality, the tongue-in-cheek humor is less impactful in Locomotives and Who Disappeared the Tallawahsaurs, perhaps because of the scale of the images and sculptures. I spend more time with the satirical social commentary of Ra’s piece The Toilet Imperative; The Geometric Redesigning of Human Tissue, juxtaposed images of governmental figures with text on toilet paper. John F. Kennedy with the word cloud “I AM SATAN” is sandwiched between photos of Fidel Castro and Margaret Thatcher. Further down the toilet tissue are images of former Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga and current Prime Minister Andrew Holness, mocking the prospect of economic prosperity for the country, which is a timely critique given Jamaica’s socio-economic state.

Amongst the paintings in the exhibition, Shediene Fletcher’s mixed media works stand out with the use of goat skin as a textural element. I am curious about how a greater embrace of abstraction could influence Fletcher’s work, particularly when so often the human figure is the central focus of Jamaican painters. Seek I and Seek II are included alongside a more conventional albeit beautiful portrait by Greg Bailey, Bro Two Crests and Art School Confidential, an oil painting by Kimani Beckford. Philip Thomas’ iconographic paintings pays homage to Kerry James Marshall’s critically haunting work A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980) with an impeccable attention to detail. His piece Marshall conjures an affect that is intentionally vacant.

Above: Petrona Morrison | Covid Diaries I and II | Digital Collage | 60 x 40 inches | 2021.

Tevin Lewis’ mixed-media installation seamlessly incorporates a range of materials, such as ackee seeds and snail shells. I am intrigued by his exploration of biomimicry and the evolution of arthropods as a site to dissect conceptions of the human being. The installation includes a soundscape recorded by Lewis, including a baby crying and distant voices, adding to a multi-layered sensory experience. Brad Pinnock’s Race Apocalypse examines psychological struggles of Black people living under the continued effects of colonialism. Intellectually rigorous, the color scheme adds a child-like humor but overwhelms the aesthetic qualities of the lotto gambling cards employed in the collage.

Camille Chedda’s mixed-media collage, We all live under the same sky, drawing on her now familiar use of cinder blocks with images inside and questioning the transformation of the Rose Hall slave plantation in St. James, Jamaica into a luxury golf course and tourist attraction. The placement of archival and contemporary photos of the plantation are jarring, serving as a reminder of the continued presence of slavery in Jamaica and the superficial shroud placed on histories of violence. Having seen Chedda’s work made with real cinder blocks, instead of using photos to represent them, I am moved more by the concept than the execution in this piece and yearn to see her work on an even larger scale.

The exhibition would have benefitted from greater curatorial risks, experimenting with the space of the Olympia Gallery and the possibility of more installation work. The positioning of the pieces created a viewing experience that at times felt disjointed. I am particularly excited by the inclusion of the younger artists, such as Hinds and Lewis, whose work pushed conceptual boundaries. I look forward to seeing contemporary Jamaican artists being increasingly publicized in this manner and the staging of exhibitions in more non-conventional gallery spaces.

For more images and information about the artists in the exhibition, please view the digital catalog.