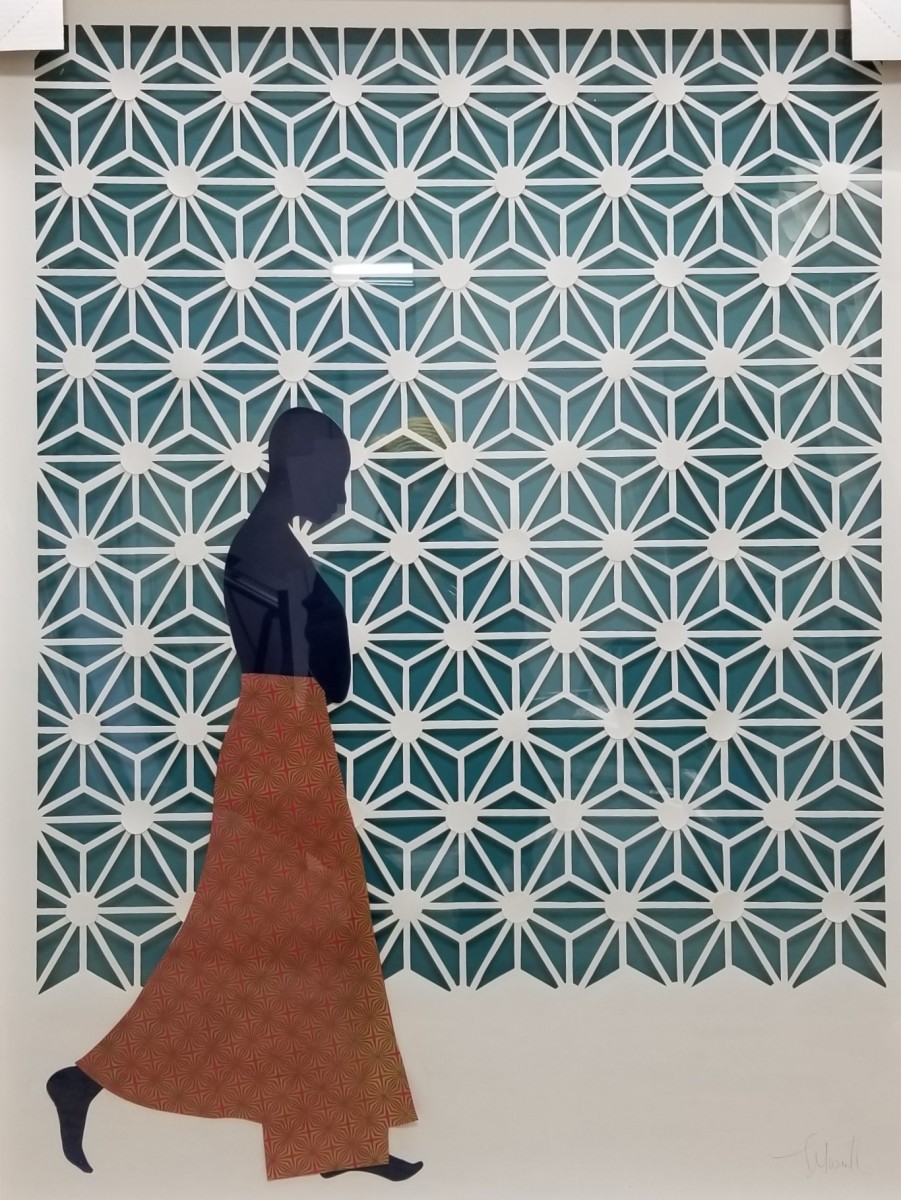

Mario Moore’s art exhibition entitled, Enshrined: Presence + Preservation is open to the public from June 3-Sept. 19, 2021 at the Charles Wright Museum of African History, Detroit. The exhibition showcases a selection of works from the artist’s career from 2010 to the present, including paintings from his most recent collection, The Work of Several Lifetimes, in which he painted portraits of Black men and women who held blue-collar positions at Princeton University, portraits which starkly contrasted those of donors, presidents, and other influential figures (who were primarily white and male) and highlighted the significance of the lives of those he captured in his portraits.

Above: Mario Moore, Several Lifetimes.

As the first exhibition to showcase Mario Moore’s work across much of his career as an artist, Enshrined contains two works from his early career—before his pivotal graduate school experience at Yale—in addition to works he created during his time at graduate school and beyond.

As a young artist, Moore was influenced by his artistic mother, and describes being “embedded in art history” as a young person. In addition to being surrounded by the Detroit artists with whom his mother socialized, “who had different practices” that he could learn from, he also was surrounded by a “breadth of knowledge about art history.”

Above: Mario Moore, Herodias with the Head of St. John the Baptist

Reading about European art history and thinking about the significance of Western paintings in museums—as well as about the “absence of the Black body” in the stories and mythologies depicted by such artworks—influenced Moore’s early work in particular. The Bible also played a major role in deciding the content of his early oeuvre, as can be seen in his 2010 pre-Yale work, Herodias with the Head of St. John the Baptist, in which Moore explores a biblical story touching on the “idea of Black men and white women,” figures that wouldn’t be put together in historical European artworks.

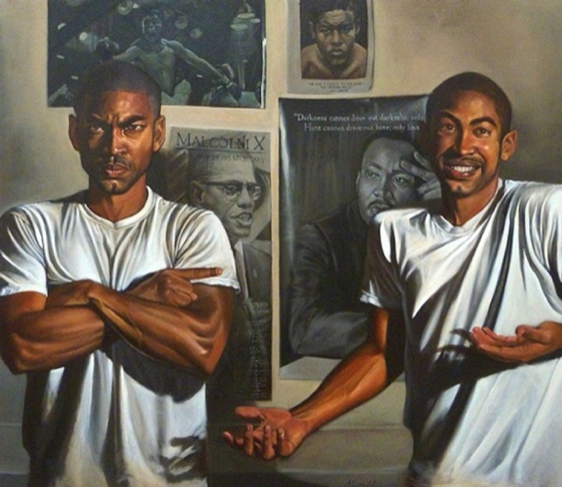

In contrast to the artist’s prior conviction that he would not attend graduate school, the challenges the prospect presented and the community of artists he knew he would be surrounded by enticed him to Yale, where he studied from 2011-2013. During that time, Moore created two of the works that appear in Enshrined: Presence + Preservation. The piece entitled Him was created during his first semester at Yale and depicts two representations of the artist side by side: one happy, one angry. Moore conceptualized the work in response to a comment made by a friend who asked him, “Why don’t you smile more?”

Above:Mario Moore, Him.

The comment made Moore consider how some emotions are expected to be concealed. Some such emotional expectations are weaponized to perpetuate harmful stereotypes against others, particularly when it comes to Black people: take, for example, the “angry Black man” stereotype and society’s belief in and distaste toward the archetype.

From this point, Moore notices a change in his painting style as he learned to experiment with mixing different mediums and materials—a leap which he cites as one of the biggest influences that grad school had on him as an artist. Such experimentation helped him avoid creating what he calls an “arid looking painting.” Indeed, throughout the exhibition, Moore paints using oil on various mediums, including canvas, linen and copper.

A signature of Mario Moore’s artistic style is his penchant for oil paints—in addition to exhibiting drawings as finished works of art, rather than merely as bases for paintings—though he didn’t use oil paints until he fell under the mentorship of Richard Lewis, another Detroit artist who encouraged him to use oils. After struggling to use the paint at first, Moore grew to love it: the oil paint took longer to dry than acrylic, so the colors could be mixed more carefully and purposefully. Moore states that “a whole new world opens up with oil painting.”

Above: Mario Moore, That Beautiful Color.

This feature of oil paint proved crucial in paintings such as That Beautiful Color, a 2016 work in which a Black woman is depicted wearing a navy dress set against a dark background. Despite the dark hues, Moore didn’t use any Black paint, instead choosing to mix blues, umbers, greens, and reds “to give different depths of black,” This technique underlines Moore’s belief that, at its heart, “Black is a combination of all colors together.” For this reason, the artist never uses pure black paint to depict black skin, and this can be observed throughout the works in this exhibition.

Another characteristic of Mario Moore’s artistic style is his penchant for depicting important figures within his own life, such as his family members and his wife, within his works. This makes many of his portraits intensely personal. Moore explains that “when you start with specificity, it opens up a conversation to bigger ideas,” so by using his own life and story as the muses for his artwork, he hopes that others can see “part of their story.” Moreover, Moore notes that historically, in Western and European painting, “the Black figures have always been in the background.”

In contrast, Moore wants to make his artwork specific; he wants his representations of Black bodies and of the significance of Black lives to bring the spectator to understand that “this is a real person.”