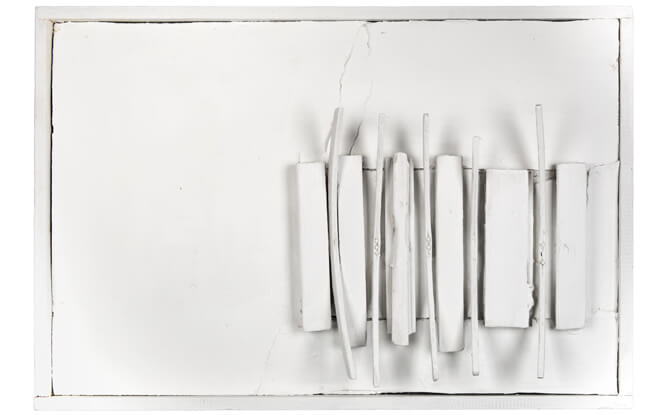

Above: Invisible Man by Telvin Wallace

An exhibition at Allouche Gallery in New York City, Operation Varsity Blues, features a group of 13 artists who are responding to the eponymous 2019 college admissions scandal, where affluent families conspired to influence undergraduate admissions decisions at America’s most competitive universities. The works on view include paintings, works on paper, sculptures, videos and mixed media installations by Lindsay Adams, Lindsey Brittain Collins, Debra Cartwright, Kevin Claiborne, Alteronce Gumby, Lanise Howard, Jeffrey Meris, Robert Moore, Rashaun Rucker, Malaika Temba, Khari Turner, Telvin Wallace and Esteban Whiteside all reflecting on structural inequities—from debt to stereotype threat—within the American educational system.

In the United States, access to professional opportunities, including but not limited to access to representation within the gallery system is formally and informally regulated through the academic networks of elite private universities. Interestingly, the CVs of the artists in Operation Varsity Blues reflects this access, as many of the artists (as well as curator Charles Moore) are currently enrolled at or are alumni of elite institutions.

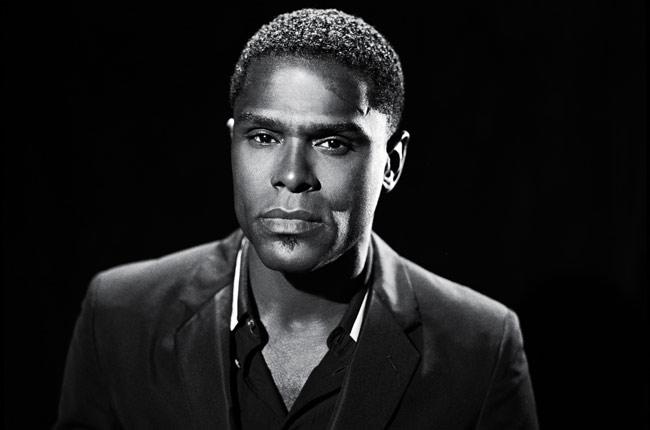

Above: Sacrifice by Kevin Claiborne

For example, Kevin Claiborne, who is both enrolled in the Columbia Master of Fine Arts program and represented by Theirry Goldberg, has three works on view that set up the impossibility of escaping to freedom by way of accruing professional power. Claiborne considers the struggle to sustain visibility as an individual artist in an extractive art world (Sacrifice, 2021), while also being hyper-visible to law enforcement. Through the juxtaposition of an installation referencing New York Police Department barricades used to surveil and control the flow of protestors (Gambit, 2020), Claiborne’s appropriation of this equipment hits a chord of shared frustration, yet is ironically poignant given Allouche Gallery’s own impressive real estate and proximity to the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The goal of many American artists to “get into the Whitney” ties together the value of art as private property and the ongoing acceptance of systems of privileged access that maintains the status of our elite institutions. The American dream is a catch-22 for racialized people, wherein dreaming of being the ones to “make it” seems to also entail that the vast majority of others will not.

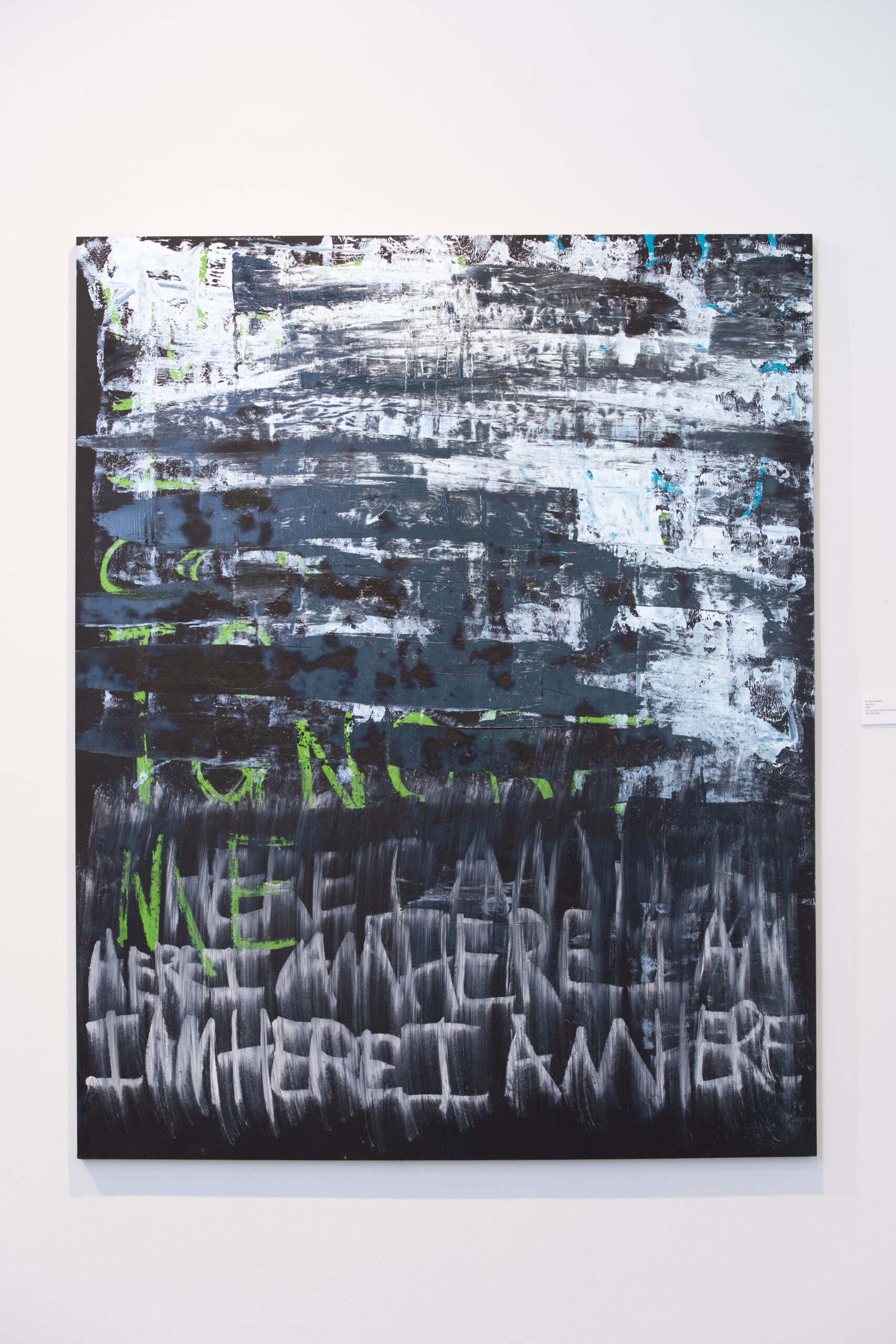

Above: Debt by Khari Turner

Khari Turner’s mesmerizing diptych, Debt (2021) applies sand, ink, acrylic, and water from the coast of Senegal, Ghana, lower Manhattan, Lake Michigan and the Milwaukee River. The impression of the gritty liquid no longer bounded by the title’s respective geographies spreads out in swipes and splashes, combing together the flows of vast heritages and symbolizing countless migrations. Turner’s surface perhaps imagines overwhelming any straightforward narratives of identity to better show the chaotic clashing between any claims to true belonging within our unevenly represented diversity of cultures.

Above: I Wear The Other When It Is Convenient by Rashaun Rucker

Across the exhibition, magnificent titles abound, which fill the works with the tension of the exhibiting artists. Although according to the press release, many of the artists are unfortunately used to being othered, there is also an acute understanding of themselves as belonging to the rarified world of the art gallery.

Rashaun Rucker’s I Wear the Other When it is Convenient (2021) is an exquisite drawing in graphite rendering the classic, light-haired letterman, referencing a specifically American tradition of hero worship, who holds the decapitated head of a dark-skinned man with locks instead of a football. Esteban Whiteside’s two large paintings in acrylic and crayon—Ameritocracy 101 and Last Question Got Me (both 2021) —cuttingly posit the open lie that answers the impossible hypothetical: What could be the path to success for an American that requires our submission to discipline at every turn and still leaves most people in this country empty-handed in an utterly rigged system?

Above:A Moment of Clarity by Lanise Howard

The figurative works by Telvin Wallace and Lanise Howard are absolutely striking and technically masterful. Howard’s A Moment of Clarity (2021) shows a Black femme at rest. This image is already a scene filled with political power, because she is comfortable, and her rest is protected, if only for a moment. She sits here with legs bent and feet tucked under the cushions after being on her feet all day. The aftereffects of her physical exertion are associated not merely with manual labor, but with every kind of hustling in a world that systematically undervalues contributions to any field by Black women.

Wallace’s Invisible Man is haunting for the ways that it recalls what has not changed for us since the publication of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel by the same name. How has Ellison’s invisible man become even less visible today in the form of the writer or artist who is uninterested in social media, for example?

What does it mean for Black artists today to both have proximity to the hyper-wealthy, yet still remain unseen in terms of the systematic restructuring of our society, a restructuring that would require the total reconfiguration of the world, not least of which would include the reparations owed to indigenous people and African Americans? Is it enough to see ourselves when the system requires that we submit to narrow forms of representation that nearly turn Black artists into mascots for assets that are primarily held by white elites?

Charles Moore’s curatorial work at Allouche Gallery would appear to be an exception to the rule. Both curator and collector, as well as a current Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University, Moore also authored the recently published book The Black Market (2020). What happens when the bare minimum for access to the art world or institutions comes by way of elite academic programs, while the market becomes so overly saturated that few are likely to sustain careers? Should there be a limit on speculating on the identities of artists? And if so, how could such a regulation be enforced? What incentives are there for galleries and collectors to regulate themselves?

Overall, I enjoyed this exhibition. But there does seem to be something of a repetition of the very topic of concern. Despite the discomfort of there being so much alienation, there seem to be no real alternatives to the current system. This means that even the writer of this review is headed to the Whitney Independent Study Program this fall in order to secure a more sustainable career as a critic of a market that seems wholly dependent on high-net-worth collectors, gossip and popularity contests. Still, art is worth it!