Above: Emma Amos. Baby, 1966. Oil on canvas, 46 1/2 × 51 in, 118.1 × 129.5 cm

In the late Emma Amos’s recent retrospective, Emma Amos: Color Odyssey, we find an artist who was an educator, painter, weaver, printmaker and refined colorist. Describing every step into her studio as a political act, Amos’s work features complex, and at times, disturbing, conceptualizations of her experience as a woman of African, European, and indigenous-American descent during her 83 years of life.

Currently on view at the Georgia Museum of Art, the 60 artworks in this show stem primarily from Amos’s estate, private collections, museums, and works held by RYAN LEE Gallery, who has represented Amos since 2016. It is the first retrospective to include work from every decade of Amos’s 60-year career, and Curator Shawnya Harris constructs a multifaceted space for visitors to experience Amos’s shortcomings, struggles and achievements as one of the most indelible artists of her time. The gallery walls are adorned with shades of red, green, white and blue to compliment the show’s themes: Bodies in Motion, Falling, Stars and Stripes, Muses, Models and (Men)tors, New York and Spiral, and Inventing the Human Figure.

The gallery’s facade includes a breathtaking painting of Amos and her late husband Robert Levine. Large-scale and painted to honor him after his death in 2005, Paths is one of few works where Amos appears blissful. She imagines her marriage across multiple shades of gold with a loving aura, shared between her and her husband, as borders of African fabric comprise the painting’s frame. This artwork, paired with those illustrating her family’s famous Amos Drugstore in her hometown of Atlanta, function as a small family album that illuminates her middle-class childhood and legacy as the granddaughter of the first licensed Black pharmacist in Georgia.

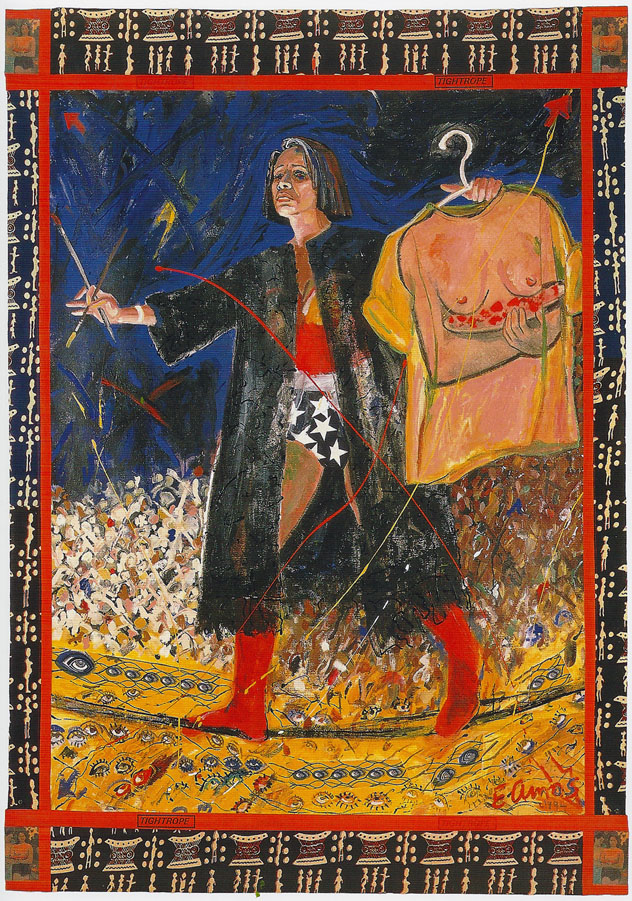

Above: Emma Amos “Tightrope” 1994 Private Collection

Amos’s Tightrope (1994) captures the essence of this exhibition. In this self-portrait, she straddles a tightrope and adorns her figure in a superwoman outfit as she characteristically confronts her position within the world around her. Amos addresses motherhood and womanhood, along with her work as a businesswoman and artist while carrying a T-shirt of artist Paul Gauguin. Based on the wall text, Gauguin was accused of marrying and impregnating his 13-year-old Tahitian muse. Amos’s choice to carry an image of his work seemingly rejects white men’s exoticization of women of color and challenges the normative exemptions offered to white men following their indiscretions.

In the same year, Amos painted Work Suit (1994). African borders envelop Amos’s self-portrait where she critiques white male artists’ abuse of power. Her head sits on the shoulders of artist Lucian Freud and oscillates between his self portrait, Painter Working, Reflection (1993), and her own conceptualization of life at the seat of male power. Amos’s left hand holds a painting with her ‘X’ motif etched onto the canvas. Similar to Tightrope, her right hand possesses her paintbrush, further signifying the balance she must strike between working as an artist and as a woman of innumerable roles.

Omnipresent in Amos’s work is her struggle with her identity and inability to find a place within an art industry that was never built to include her. Though her critique of artists Matisse, Freud and Picasso prove beautifully crafted, the tension between Amos’s ideas of equality and choices in subject matter complicate her desire for freedom. By placing her head on the shoulders of the men whose power and oppressive acts have subjugated her to the point of marginalization within the mainstream, the overall aim of her work is often obscured by Amos’s internal struggle to obtain inclusion within an institutional structure she so avidly fought against.

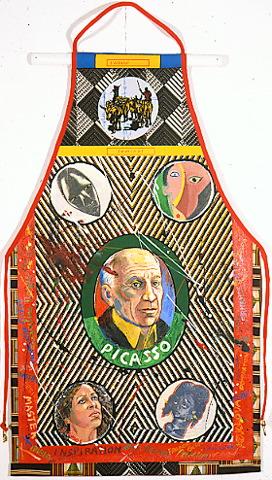

Above: Emma Amos, Muse Picasso, acrylic on linen canvas with African fabric borders, 60″ × 32″, 1997

In her Muse Picasso (1997), for example, her face looks up in confusion and admiration of artist Pablo Picasso to critique his position as a master artist and dominant figure. As she examines his position and appropriation of African art forms, she attempts to signify herself, too, as a master artist. This approach to deconstruction is compelling but elicits reimagination. By literally and figuratively centering Picasso as the embodiment of mastery, Amos’s decision rejects the possibility that her skillset may precede European notions of artistic hegemony. Instead of theorizing beyond this belief, Amos’s work upholds the European idea of mastery in art, which often comes at the expense of an Other and marginalization of another artist(s).

Therefore, Amos’s decision to situate herself beside a European master and genius-like figure affirms the power structures associated with whiteness. Though well-intentioned and compositionally sound, one can only imagine how this painting might have looked different if Amos viewed herself beyond the standard of Picasso’s supposed mastery. Based on her willingness to grapple with such intellectually rigorous concepts, however, her work reveals a certain promise that deems her an artist whose interests in creating visually appealing work never preceded her ability to articulate theoretical approaches in her practice.

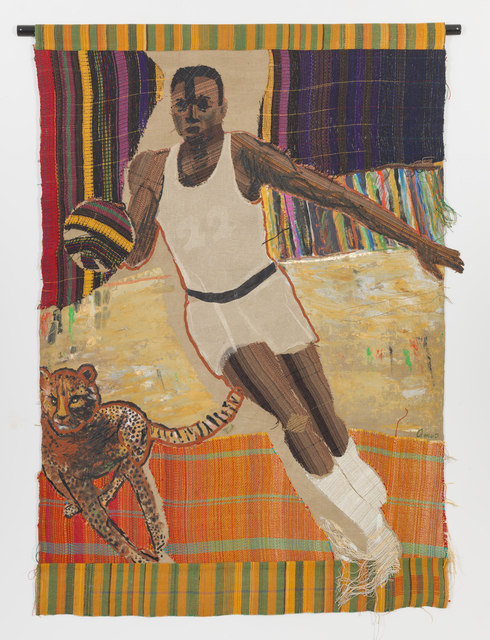

Above: Emma Amos, 22 and Cheetah, 1983, Acrylic and handwoven fabric on linen, 84 × 62 in

213.4 × 157.5 cm

Amos’s desire “to steal ‘male power’” inspired her 1980s paintings of athletes. In 22 and Cheetah (1983), she depicts Clyde Dexter, who was a member of the Portland Trail Blazers and 14th overall pick during the 1983 NBA draft. Basketball in hand with a cheetah beside him, Amos visualizes Dexter through notions of corporeal power and feline agility and layers his figure in handwoven fabric and acrylic.

She also includes images of female athletes in Runners with Cheetah (1983) to celebrate the contributions of female sports competitors. In her Falling Series and swimming imagery, however, Amos’s work appears completely unbound. Some of the notable works from this section include her triptych, Flying Circus (1987), as it covers one singular gallery wall, as well as her paintings of swimmers in Tumbling After (1986) and The Raft (1986).

Though Amos never learned how to swim, she used her paintings to imagine herself a swimmer and to celebrate the small number of Black swimmers who competed in the 1984 Olympics. When viewed in person, these particular works reflect Amos’s determination for freedom and transcendence beyond the oppressive aspects of her life.

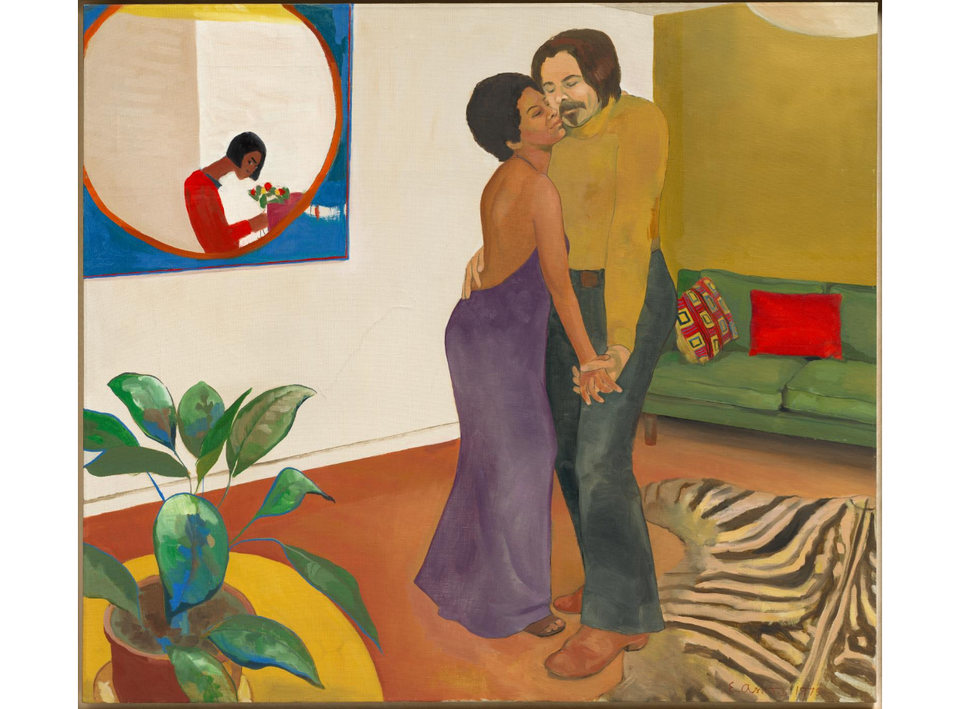

Above: Emma Amos, Sandy and Her Husband, oil on canvas, 44¼ʺ × 50¼ʺ, 1973

Lastly, in the largest section of the exhibition is an abundance of archival materials, early abstract paintings, and esteemed artworks such as Baby (1996) and Sandy and Her Husband (1973). This particular section of the exhibition serves as the culmination of Amos’s career. Materials from her time spent as an illustrator for Sesame Street magazine, among other works as the only female member of the Spiral Group, support the visual timeline that displays her accomplishments throughout the main gallery.

A graduate of NYU and Antioch College and a 28-year Rutgers University art professor, Emma Amos’s Color Odyssey achieves higher ground by recognizing an artist who remained committed to her practice even as she fought Alzheimer’s through her transition in May 2020. Honest, critical, and profoundly colorful, Amos teaches us that there is more to life than the categories or definitions others use to define who we are.

Writer’s Note: Upon writing this piece, I learned Amos Drugstore was where my maternal grandparents met. While pursuing their undergraduate degrees at Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University), my grandmother Sylvia (Ann) Lee Jones worked at the drugstore and sold hot dogs to my grandfather Theodore Roosevelt Jones Jr. This interaction was the catalyst for their marriage of over 50 years and is the reason I am here today. Amos also attended Booker T. Washington High School during the same time as my grandmother, as she was three years Amos’s senior. – Jasmine Wilson