Above: Evelyn Politzer, “Every Drop Counts,” 2018. Hand-knit wool.

The forced labor of enslaved Africans dispersed throughout Europe, the Caribbean and the Americas was foundational to modern capitalism. Humans subjugated by race were traded as assets. Stolen from their native land, their bodies were monetized and their humanity stripped.

Today, this system may take new forms, but it requires the same exploitation of land, natural resources and human labor for continuity. These immense value degradations touch almost every aspect of economic exchange. In Inter | Sectionality: Diaspora Art from the Creole City, 26 artists, representing 17 countries. The intergenerational exhibition includes artists from 22 to 71 years of age.

In contemporary art, items of the marketplace are frequently used to symbolically convey this history. Repurposing found objects adds to the narrative, compounding the meaning derived from personal experience, as expressed in a visual, material conversation through metonymy, using one object to represent a point in history. In Michael Elliot’s Windrush Series tea is a commentary on the British relation to the Caribbean.

Teabags disperse their flavorful, herbal medleys into still, hot water. Tea provides relief, nourishment and pleasure; once satisfied, the consumer throws the teabag away. The possibilities of the tea’s properties are limited, bound to their function as temporary sustenance.

The production, dining culture and ontological meaning of tea resonate differently across the globe. Arguably, however, British aesthetic and cultural identifiers serve as a universal reference. The British tea market and culture, given their political and socioeconomic use, have produced a visual iconography that transmits Britain’s national history.

Above: Empire’s Pot, Michael Elliot

Michael Elliot offers a new view into the familiar. In Empire’s Pot, the arm of a Black man is merged with a kettle, forming its spout. A pendant of a Black man kneeling in servitude, an emblem of British economic iconography, crowns the patterned ceramic.

Overlaying symbols, he further embeds histories onto objects that carry global significance in their function and ritual.

Many of the works repurpose found objects and material culture, embedding meaning through text, placement, performance and collage. The exhibition, both through its process and presentation, showcases the importance of the artist traveling with the object. The exhibition, developed by two immigrant curators of color, situates the identity of the curators and their cultural proximity to the environment of the artists’ production as valid tools.

Like the remnants of the teabag whose contents float in still water after its removal, knowledge is held in the lived experience of the artists’ environment and cultural orientation. The Western art canon holds cultural assets in their esteemed collections; these works are removed from the environment of development and its conceptual cues.

Akin to cabinets of curiosities, collections hold historic relics and works of art from global communities.

Collections and exhibitions in the West that feature international works tailor their viewing experience to the host audience. The language used to discuss the work is often separated from their original locales and is relegated to the reference availability and epistemological orientation of the institution, the curator and the viewing audience.

This adversely affects Black and Brown artists, as curators of major institutions often represent a cultural difference. A 2018 survey conducted by the New York Times shows that only one of the top 13 art museums in the United States has people of color reflected in at least half of their curatorial staff. The survey does not specifically address Black staff members, the identities under the broad-reaching moniker “of color” is vague.

Interpretations of artworks are intellectualized, formed by the figures and histories that are represented in academia or mainstream culture. However, narrative is given authority and lived experiences are validated by placing the artist in the room, or through curatorial relation with artists and their environment.

In Ngugi Wa Thiong’o’s seminal text, Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms (1993, London: James Currey), the chapter, “The Universality of Local Knowledge,” addresses the challenge of representation and its consequences. Thiongo asserts, “shifting the focus of particularity to a plurality of centres, is a welcoming antidote.” (Thiong’o, 1993, p. 25)

This shift of narrative making is a welcome correction to the hegemonizing of international communities in often well-intended efforts to draw “universal” themes as understood by a Western audience. In the process of universality, much of the cultural nuance is ignored for a shared, palatable presentation. Thiongo expounds the influence of environment on cultural production:

Culture develops within the process of a people wrestling with their natural and social environment. They struggle with nature. They struggle with one another. They evolve a way of life embodied in their institutions and certain practices. Culture becomes the carrier of the moral, aesthetic and ethical values. At the psychological level, these values become the embodiment of the people’s consciousness as a specific community. (Thiong’o, 1993, p. 27)

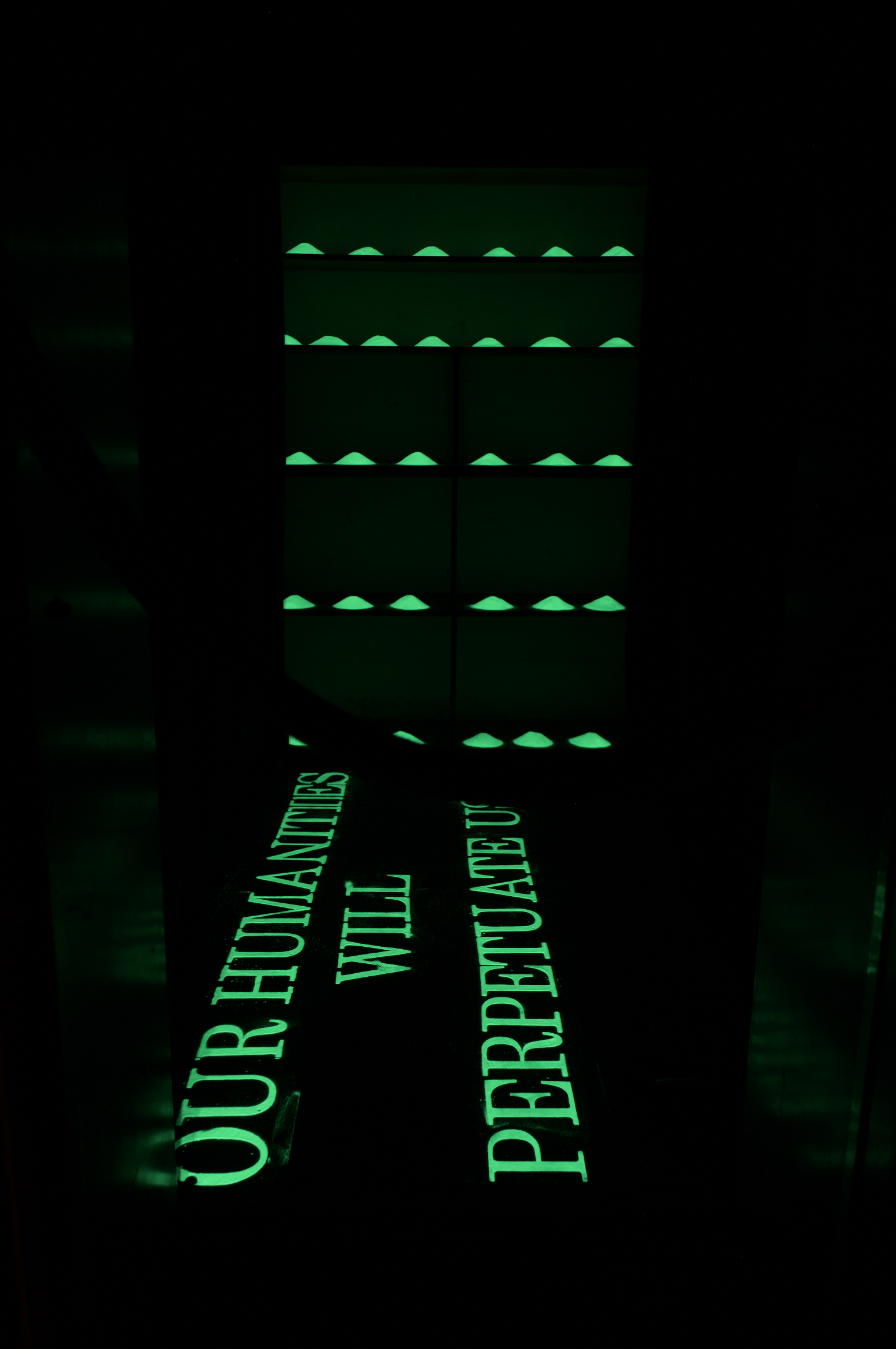

Above: Juan Ernesto Requena, “OUR HUMANITIES WILL PERPETUATE US,” 2019. Phosphorescent pigment, stencils.

In Inter | Sectionality, environment is foregrounded through the artists’ presence, the selected works and catalog writing. The curators directly address the expected themes attributed to the Caribbean art presented in the United States. Caribbean art, like the West’s engagement with Caribbean tourism, centers the physical landscape instead of encompassing the full, lived experience.

Instead of featuring works that display sunsets and oceans, the space itself subtly presents the Caribbean’s natural environment through lighting and the predominant colors of installation and abstracted works. The abstractions do not necessarily speak to the environment, but their colors are used functionally to convey water, natural textures and the sun.

The intersectional approaches to hallmark themes, such as environment, spirituality, matriarchy, politics and queerness, also widen the experience of contemporary Caribbean art. The exhibition is co-curated by Rosie Gordon-Wallace and Sanjit Sethi. Gordon-Wallace is the founder and director of the Diaspora Vibe Cultural Arts Incubator (DVCAI). Sethi is the president of the Minneapolis College of Art and Design; he served as the director of the Corcoran School of Arts and Design from 2015 to 2019. The exhibition began in 2018, while Sethi held a directorship at Corcoran.

In its vast approaches to intersectional representations of the contemporary Africana aesthetic, this landmark show expands the presentation of visual language and art histories told by Black artists and scholars. The works are multidisciplinary, including performance, film, photography, installation, sculpture, and painting. Presented works are informed by traditional, cultural, domestic, and ritual practices rarely documented in text or espoused by their communities in global, public arenas.

The exhibition is an act of decolonization; the visual experience is not relegated to reproduction of familiar, traumatic histories, but it is expansive in emotive reach and topical connection. Gordon-Wallace shares, “We work inside out, in diaspora and from diaspora. You cannot talk about diaspora work without referencing the continent of Africa.”

Moving the center to the diasporic hemisphere, the works embed native practices; this radical shift is most necessary to move the emotive aims of institutional diversity and inclusion into equitable, actionable, and sustainable outcomes.

Shifting centers through alternative narratives is hinted in the title, Diaspora Art from the Creole City. Widely known as the Magic City, Miami is referenced here as the Creole City. Donette Francis expounds upon this linguistic shift in her catalog essay, and her book in progress, Creole Miami: Black Arts in the Magic City.

Miami is situated as a Creole city, given its diverse Caribbean cultures and the European and African influence on language, spirituality and artistic production. In naming the city Creole, rather than magic, she situates the cultural blending as the extraordinary factor. Through this reference, the unique qualities of the city’s arts and culture may be cited to their ethnocultural cues and the co-creation that occurs with the close proximity of diverse groups. The works in the show have all traveled through Miami either physically, relationally or conceptually.

Devora Perez’s Man-Made Environment (here, there, and everywhere) incorporates concrete and gravel to assemble a horizon skyline. The work speaks directly to locale; Perez is originally from Nicaragua and is now based in Miami. This dark horizon, assembled by industrial material, places an image usually embodied by natural landscape with man-made mass.

For immigrants venturing to the United States for safety and in “the pursuit of happiness,” their dreams are often confronted with man-made systems, environments and again, the residual effects of capitalism. These confinements exist at the border and inside the new country. At the same time, Perez brings attention to rapid gentrification in her environment. Miami’s renowned natural beauty and cultural landscape are threatened by man-made structures fueled by capitalist gains.

Above: Kurt Nahar, “Bleach1 and Bleach 2,” 2018. Acrylic paint and paper collage on hardboard.

The inclusion of Kurt Nahar’s BLEACH 1 and BLEACH 2 express the shift that art may enact on quotidian knowledge. Through color and space, Nahar emphasizes the absurdity of People of Color globally described as “minorities,” or “third world people.“ In BLEACH 1, the text “BLACK” is overlaid on a black globe. The globe is afforded white space in the shape of the United States and Europe, which is overpowered by the presence of blackness.

The reverse effect is shown in BLEACH 2. In both works, Nahar expresses the physical presence of melanated communities who actually comprise the majority of the world’s population. This gesture, and its embodied title, play on words and their power to misdescribe reality.

Caroline Holder’s Insomniac’s Menagerie is a satirical, narrative installation. Holder pulls from her experience as an older mother of Jamaican and Barbadian heritage. “A woman of color fades into invisibility behind a stroller,” is the text that adorns one of several ceramic pillows hanging above a black bed frame. The pillows convey the thoughts that keep Holder up at night, some of which are connected to her role as a mother. In her home of New York City, she is the assumed nanny of her lighter complexion child, and is treated as such in public spaces.

Next to the bed is a large “monkey jar.” The monkey jar in Caribbean homes holds secrets. Often, items are thrown into the jar when guests arrive. Monkey jars were vital in sustaining family heirlooms and sacral items during times of colonial presence and terror.

The exhibition has a substantial curatorial statement but limited didactics. The choice to limit the wall text is to draw attention to the exhibition catalog, and to unify all didactics in an exhibition that uses walls, floors and pillars. Audiences who wish to capture other perceived meanings can research the artists’ work or the active symbolic, stylistic and conceptual cues.

Inter | Sectionality: Diaspora Art from the Creole City is an active show, the aesthetic and conceptual vibrancy begets dialogue. The centered identity of the artists requires the viewer to consider their position. The level of familiarity to the work in its aesthetic and conceptual advertence is derived from personal experience, exposure and reference availability.

As diversity continues to prevail as a defining movement in contemporary art, the exhibition presents a new consideration. The exhibition does not simply bring artists of color to white spaces, it involves the artists fully in the process. The curators employ their ways of being, regardless of the canon’s norms and expectations.

“Starting from the continent” is the primary ethos in the curatorial interpretation and audience experience. Foregrounding lived authentic experience counters the expected and familiar conceptions of the Caribbean, often devoid of connections to the diaspora.

On view from February 5-May 31, 2021. 191 NE 40th Street, Miami, Florida 33137

Monday – Saturday 11AM-7PM

Sunday 12-PM-6PM

Learn more at dvcai.org