At Dominic Chambers’ solo show in Pittsburgh, Like the Shapes of Clouds on Water, I met Ambrose Murray and Amani Lewis. I later wanted to learn more about their connection through art. Ambrose and Amani’s art, as well as personality, exudes vibrant, creative, positive and mystical energy. Their relationship itself is a muse, inspiring their artwork and the conversations they engage in through their art.

Above: Ambrose on the left and Amani on the right. Image courtesy of the artists.

Ambrose (she/her/hers), a self-taught mixed-media collage artist, received her bachelor’s degree in African American Studies from Yale College in 2018. Amani Lewis (they/them/their), a multidisciplinary visual artist, received their bachelor’s degree in general fine arts and Illustration from Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). Together, they are a force to be reckoned with in the art world.

Exhibition Meet: Cute

Ambrose and Amani credit Kilolo Luckett, a Pittsburgh-based independent curator, with bringing them together. In 2019, Luckett curated a group exhibition, Conjuring Wholeness in the Wake of Rupture at De Buck Gallery in Chelsea, New York. Ambrose witnessed Amani’s work for the first time during this exhibition. They connected via social media after the exhibition to exchange ideas about digital collage, all the while having romantic intentions.

After months of talking, they met up for a date. Their conversations quickly entered the spiritual level, as they “drove around Baltimore talking about art, looking at houses, discussing racism and ending up at [Amani’s] studio,” Amani recounts.

Amani’s studio became a place for them to exchange ideas and delve intimately into each other’s artmaking practice. “I had works up there and we talked art, creating, visualizing and manifesting… In that moment, I felt I knew her for millennium.” Ambrose reflects that, during this conversation, she felt heard and wanted to pursue a relationship with Amani. Having met in an art context indicated that their “core values were the same, dreams were similar, and that [they] could help each other in making [their] dreams come true as the foundation of our relationship,” Amani says.

Above: Ambrose is sitting and Amani is standing. Image courtesy of the artists.

Sharing in Their Practice

Naturally, two artists dating influence each other’s work. While all relationships are about give and take, the artists’ unique circumstance allows them to explore this dynamic in their art.

“A lot of times I have heard, how can visual artists date each other? Is it going to be competitive? People see it as striving for the same thing—applying for the same residencies and going for the same prizes. Because we are both artists, we support each other. Amani is a generous person, as an artist, because they constantly share their resources—people, network, and skills. That makes it impossible to be competitive,” Ambrose shares.

The collaborative, joint practice they developed enhances their work and message of working within communities. “Working in the studio made it inevitable that we see how each other is working and taking what the other person is doing and experiencing and bringing it to our own work,” Amani adds.

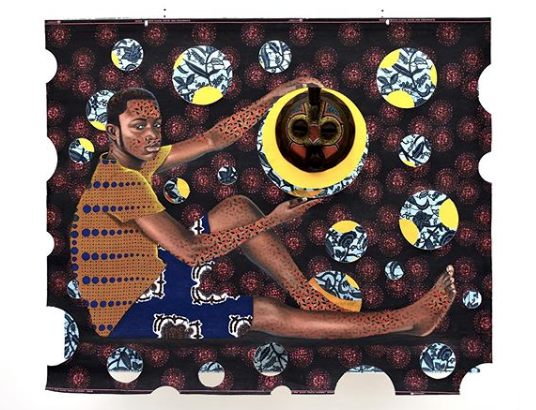

For instance, Amani adopts digital layering techniques, which is inspired by the use of textiles in Ambrose’s art. They both arrived to the medium of digital collage by mapping out physical works. Digital collage connected them even as they took the medium in different directions. “[Amani’s] use of layering, glitter, cool colors and shapes inspired me. If you look at Amani’s work, you could zoom-in on any piece, and it is a work in itself because a lot is going on with shape, color and texture. That attention to detail and finding moments of beauty is something I want to bring into my work as well,” Ambrose says.

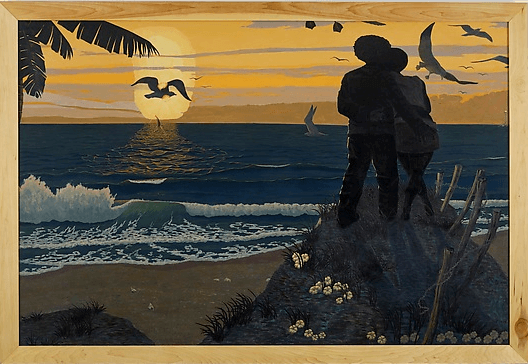

Love and visuality are languages of the couple’s practice along with a connection to the South. “There is a Southern ethos and upbringing that we have. It has to do with being generous and seeing the best in people. Storytelling is a large part of our families and Southern culture in general,” Ambrose says. Originally, Ambrose’s family is from North Carolina. They migrated to Florida, then Chicago, and her mother moved back to North Carolina. Amani’s family is also from North Carolina. Through the Great Migration, they moved to Maryland.

The history and culture of the South inspires both artists to center community stories rather than “umbrella narratives” in their work. Working with the community requires a sensitivity to preserve the voice of others. “Growing up in Maryland, [I saw] historic Confederate trails. The creation of American history, politics, and systems started in the South,” Amani says, as they note that many people write off the South as a part of American history.

“Storytelling is at the center of our work. A lot of Black artists converse about slavery and reparations. It is important that we don’t stop with the histories around slavery. [Our] Southern roots cause us not to be trapped under umbrella narratives, [but] the individual has the chance to speak their story and truth,” Amani says. As stories are central to their artwork, their relationship is another layer present in their art.

Love is a Masterpiece

Without hesitation, Amani described their love as embodying a Willem de Kooning piece, based on their favorite work in the abstract expressionism wing in Glenstone Museum [in Potomac, Maryland] where they once worked as a guide. “[Our love is] all over the place, yet beautifully curated. [Kooning] had a way of [making the medium of] paint into a conception. He painted with the brush, a squeegee, the back of the brush, letting the canvas drip down. When I think of our love story, we’ve had twists and turns. We view love with so many different facets, and I’ve never known a love like this before. Being in love with her is a journey that is timeless, and it shows in many different ways.” Amani says.

Ambrose, thinking of their relationship affectionately, compares their love to a Kennedy Yanko piece. Although their relationship is not perfect, it is multifaceted and rewarding. “When you are in a close relationship with somebody, the deeper parts of yourself get exposed. It is like a mirror that is put up to you [because it shows the] habits of how you deal with something that is hard or how you communicate. A Yanko piece is a good representation because of the hardness of the metal in contrast to the soft smoothness of the paint skins.” When you first see the “paint skins, you don’t necessarily know what it is until you dig a little bit deeper. [Our love is embodied] also through its beautiful colors,” Ambrose describes.

Black Artist Love is a Muse

Traditionally, muses in art are female models that inspire masterpieces based on the white male gaze. It is even referred to as a “one-way street.” Within the context of Ambrose and Amani’s love, this concept is disrupted, because it works both ways. Their artistic practices build off one another. A muse for them is their relationship, which is based off of the two artists in conversation with each other’s work in a way that is intimate, vibrant, intellectual and unapologetically queer. Rather than painting each other as subjects, in the nuances of their work, you see each of them in it.

Learn more about Ambrose’s work on her website and Instagram and Amani’s work on her website and Instagram.