Above: Delita Marin | Six Persimmons | 2019 | acrylic, charcoal, decorative papers, hand-stitching, relief printing, oil and acrylic on wood | 51.5 x 71.5 inches. Image courtesy of Galerie Myrtis.

In my emergence into womanhood, the many stories, prayers and unspoken spiritual blessings surrounded me. I now possess a combination of wisdom based on my foremothers: Christianity, African-indigenous religiosity, and the adages of the matriarchs in my family. Especially Grandma Watson, who received only a middle school education in the Jim Crow South; we take her words as Bible.

Sometimes the only language that they had to protect me in a world pitted against Black womanhood was the practice of self-directed healing, speaking in tongues, keeping me ”prayed up,” touching the sites of ailments, concocting holistic medications (known to me as ”funky tea,” herbal supplements, and the infamous tummy tamer—ginger ale, crackers), drowning in tears, testifying based on their past experiences, and singing to comfort me—these swirled around my being and became a salve for any problem.

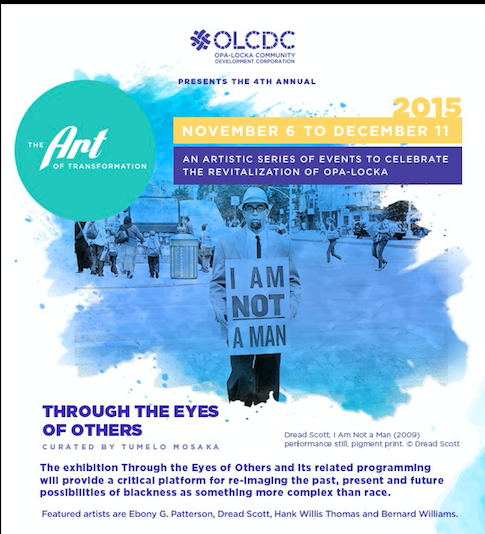

Similarly, the exhibition showcased at Galerie Myrtis by Myrtis Bedolla, Women Heal Through Rite and Ritual, delivers doses of how women of the African and Mexican Diasporas source their healing. This show is an ode to powerful women of color who delivered themselves from harm and “set at liberty them that are bruised.” The work of Tawny Chatmon, Shanequa Gay, Lavett Ballard, Delita Martin, Elsa Muñoz, Oletha DeVane and Renée Stout shifts from a Western narrative of healing to a narrative that is typically kept in the margins, moving it to the center: Women possessing agency in their own therapeutic practices.

For Such a Time as This

Women Heal Through Rite and Ritual is such a timely exhibition: it emerges during the Black Lives Matter Movement and the COVID-19 pandemic while utilizing virtual space. Since this show is so timely, it relays the information of how women heal from internalized racism and other pathologies. These ways of healing tether the spiritual, the somatic, the psychological, and the ecological to achieve holistic wellbeing. The availability of this show virtually transfers these practices so that all can view. Evidently, healing is urgently needed in today’s world. As we circumnavigate these complex and non-linear issues, a euphonious assemblage of artwork manifests healing beyond just subject matter and theme. In convergence with today’s issues, the artwork that these women artists create visually conjures healing.

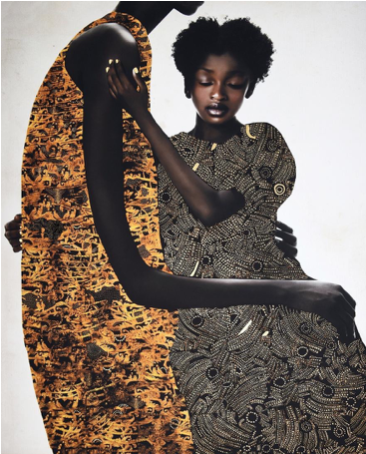

The work of Tawny Chatmon reinstates the divinity in Blackness despite forces waged against it. In her segment of Tea With Myrtis: Artistically Speaking, she discusses how her work has emerged concurrently with the Black Lives Matter movement. She places emphasis on the visual language of the Renaissance and the Byzantine art period to place divinity in Black body politic, as in Mother God (above) with its Madonna and Child-like depiction. The elongated arms of the mother with her head cut out of the frame as she hugs the child’s body represent divinity, healing through bodily touch between a mother and child, and the radical protective impulses within Black maternity. This cultivates healing by illuminating childhood and motherhood in the face of anti-Blackness. The radical act of simply being a mother and a child showcases Black resilience and self-preservation.

Similarly, Shanequa Gay evokes figures of power through her depictions of “the devouts”—mythical creatures that combine the bodies of African American women and masks of animals. This illustrates their divinity and references complex African-based cosmologies, as well as signifies the work of bell hooks (Gloria Jane Watkins) by including the idea that Black women are goddesses. This blends into the narrative of healing as the gaze shifts from looking out to looking in—for healing, saving and divinity.

Vessels of Healing: Intergenerational Coping Mechanisms Passed Down

The exhibition’s namesake conflates womanhood with healing and is a powerful statement. This statement implies the agency and self-directed healing that women possess. The discussion of symbolic subtitles and undertones in the work of Lavett Ballard and Delita Martin opens the conversation of ancestral healing through women.

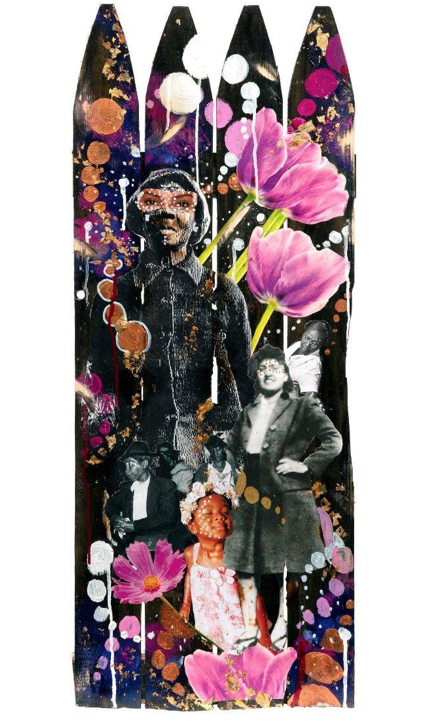

Artistically Speaking, explores the work of Lavett Ballard. Ballard takes on the media of fences, paint and photographs to create beautiful assemblage artworks. In She is Immortal, she evokes the healing contained in the bodies of Black women by referencing the story of Henrietta Lacks, depicting a midwife, church elder women, and a woman sharecropper. This spiritual and historical commentary demonstrates the healing embedded in the DNA of Black women on the cellular level, transference of touch, and mere presence of Black women. Additionally, she includes flower and circle motifs to exude the regenerative power in womanhood.

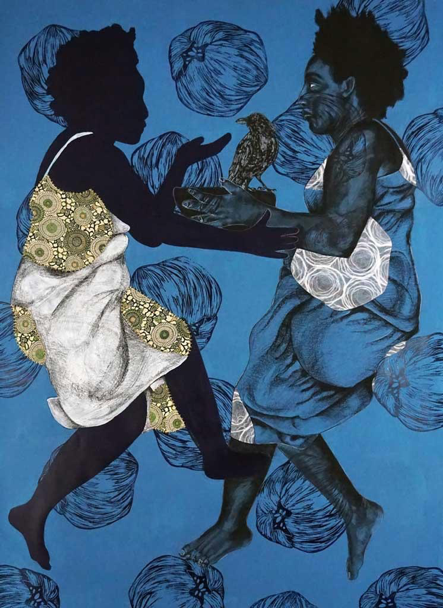

Delita Martin, also, uses the power of signifying and testifying to evoke ancestral conversations through figurative imagery and motifs. In her artwork (first image, above), Six Persimmons, fruit and birds illustrate life and the human spirit. The image of a figure looking inward to a shadow that holds her gaze illustrates reaching enlightenment, and the cosmic connection between Black women and their ancestors. Martin adds to the dialogue by encouraging familial knowledge and introspection as sources of healing.

Landscapes of Healing and Sanctuary

According to Jacques Lacan, a French psychoanalyst, madness is inextricably linked to society. Within this theory constructed by a white male, it refers to trauma as an external force coming from society. In the lives of women of color, society-linked madness is translated as trauma inflicted by institutionalized racism. The way that women create enclaves of healing is by making their own sanctuaries. Sanctuary is defined as a consecrated place of refuge, protection and immunity from outside influences. Elsa Muñoz, Oletha Devane and Renée Stout render sanctuaries of their own through making images that honor the spiritual practices of women of color to heal from the ills of society.

This concept is, most notably, shown in the work of Muñoz. Her artwork conveys healing through storytelling of her mother, accessing “Somatic Healing” and “Ecopsychology.” Essentially, somatic healing is a release from the body evoking healing, and ecopsychology is the practice of turning to the land for healing. Muñoz demonstrates this in Controlled Burn 14 by referencing the indigenous practice of starting fires as a natural and cleansing force.

As part of the spirituality of Mexican folk medicine, she presents a way of curing that is practiced through interaction with the land. This adds to the theme of healing by showing that women create their own sanctuaries both within and external to them and transfer medicinal powers through touch and storytelling.

Oletha Devane quite literally creates sanctuaries of found objects. This bricolage practice combines African diasporic religiosity into powerful sculptures. In Artistically Speaking, her work is noted as possessing healing because of the past lives and energy within the objects. This mimics the stance of the other artists that Black women heal from within, but Devane discusses this through an object-based approach.

In Sanctuary, she plays with the concept of refuge with mirrors which represent reflection, keys which represent possibility and to the viewer indicate access and unlocking, the black apple which represents the Black body, and bullet casings, at the border of it, which represent Black death through violence. Through her coding and symbolic depiction, she illustrates the path of healing from violence to the Black body through material culture and creating our own sanctuaries.

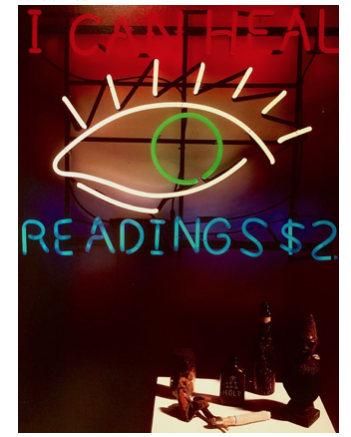

In the same vein, Renée Stout cultivates timeless depictions of the concept of sanctuary. She uses contemporary neon lights and objects that represent African indigenous religions in I Can Heal, to showcase the healing practices of Black women throughout time. Not only is the title of this work a declaratory statement, but she shows how the “I” heals overtime by carrying past structures with them. There are many signifiers in this work such as the eye, the illumination of the lights, the bottles, and the figures. These all point to the clarity in hybrid ways of knowing and seer women who are able to navigate this world of spiritual and ancestral, of natural and physical. Overall, Stout articulates the sanctuary in the multiple ways of knowing within the African diaspora.

Benediction: No Weapon Formed Against Us Shall Prosper

The artwork of Women Heal Through Rite and Ritual celebrates the restorative techniques practiced by Black and Brown women in lieu of modern-day psychological practices. Talk therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and prescribed medications either were not available to these women or failed them. Instead, they sought Afro-indigenous practices that grounded them in spirituality and medicinal practices.

These women masterfully access the nexus of escapism and confrontation in their practices. The knowledge that Black women possess through storytelling, diasporic connections, and the healing within our being assures that no weapon against us shall prosper. No force can extinguish us because our healing comes from within.