Many years ago, Nellie Ricks, my great-grandmother, sent me on an errand. It landed me at Mrs. Gertrude Ellison’s in southwest Atlanta. I parked in front of her sage-colored house and readied for a conventional exchange of Southern gentility with one of my grandmother’s old friends. I was greeted at the door by a petite woman in her 80’s. She escorted me to the living room where several dozen Ebony and Jet magazines aligned the carpet in neat stacks. Noticing my interest, Mrs. Ellison revealed she had a collection that dated back to the 1950’s. Without hesitation, I asked permission to take a peek.

Sheltered in the darkness of her basement, I found decades of vintage Ebony and Jet magazines. Awestruck, I browsed issues dated before my own mother’s born day. As Mrs. Ellison looked down from the top of the stairs, I reflected upon how each of the hundreds of issues was once current and lived comfortably in her home. Similarly, the Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation exhibit at Spelman College Museum echoes the wonderment I experienced at Mrs. Ellison’s.

The Johnson Publishing Company was founded in 1942 by John H. Johnson, with the purpose of featuring content for Black Americans, a demographic that publishing houses significantly overlooked and undervalued. Mr. Johnson, armed with vision and determination, set out to fill the void. In 1945, Ebony magazine launched and circulated monthly. Jet, the compact little sister to Ebony, arrived in 1951 and circulated weekly.

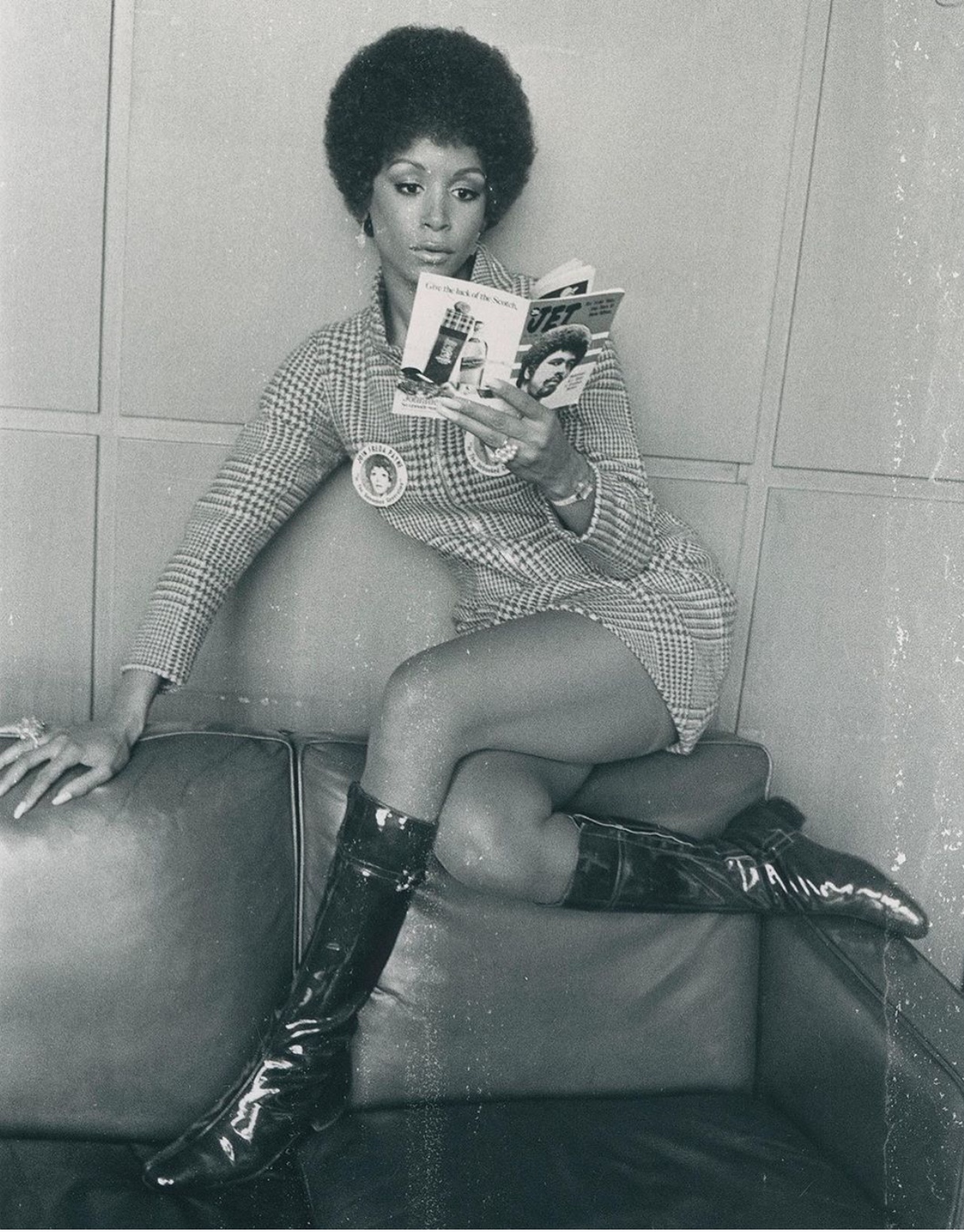

Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation captures a specific moment from the Johnson archive. The exhibit features exclusively, photos of women from the 1950’s, 1960’s and 1970’s shot by Johnson Publishing staff photographers Moneta Sleet Jr. and Isaac Sutton. They covered a spectrum of activity, from editorial to fashion, offering a consistent yet broad survey of images. Notably, Sleet won the Pulitzer Prize and gained seismic attention for his iconic 1968 photo of Coretta Scott King mourning at her husband’s funeral.

These magazines served a refreshing perspective of Black life, featuring articles on culture, current events, entertainment and sports. Across America, Ebony and Jet magazines were common fixtures in Black homes, and included topics relevant to our lives, from the Civil Rights to the Obama era. Ubiquitous, spanning generations and widely recognized as the leading source chronicling Black life in America, their cultural and historical impact was unprecedented.

Like a pulse, Ebony and Jet stayed on beat with Black culture, and by the 1980s, the magazines’ formidable reach encompassed over 40% of Black adults in the U.S. In homes and businesses alike, issues gleamed like tokens of Black cachet from tabletops, racks, shelves, or even were collected and stacked ankle-high, like in Mrs. Ellison’s living room. Ebony and Jet thrived well into the 21st century, but like most print publications, the ascension of digital media disrupted growth.

In 2016, Ebony Media was sold to a private equity firm but retained rights to its exceptional photo archive of nearly 4 million historic photographs. Shortly after, in 2019, the company filed for bankruptcy and prepared to liquidate its valuable archive. The Black art, historical community experienced considerable heartache regarding the fate of the monumental collection. Igniting great relief, it was finally announced that the complete photo archive, including prints and negatives, sold to a consortium of foundations and were donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Getty Research Institute. Prior to the sale, Gates licensed the image rights to produce Black Image Corporation. He shares the significance of enterprise and art in a 2018, 032c.com article:

“…certain artistic material forms can only emerge as the consequence of business. An example would be Richard Serra needed a shipyard in order to cast the rolled, steel pieces that he was doing in Germany. In the absence of the boating industry, one couldn’t make major modernist works. In order to exhume the Black image from Johnson Publishing I had to license the right to those images. I had to hire a lawyer. I had to put my money down. I had to move a team of six scanners, administrators, into the Johnson office because they didn’t want their images to leave the space for security reasons and licensing reasons. I was a business. I was a parasitic business inside a dinosaur…If no one’s willing to deal with the truth of my contracts, my negotiations, then that’s where my f*cking genius is. And if you imagine that the intensity lives only in the final output of the thing, you’re wrong. I’m not even talking about process. I’m talking about procedure.”

With this exhibit, Gates revives Johnson Publishing Company as the commercial institution that served as the world’s first, major custodian of Black culture.

Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation launched internationally in 2018 at the Fondazione Prada, Osservatorio in Milan, Italy. The exhibit arrived at Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in early 2020. Often considered the crown jewel of the Atlanta University Center, which includes Morehouse College and Clark Atlanta University, Spelman is the only historically Black college with a women-only student body.

Significantly, the Black Image Corporation photo subjects are all women. The exhibit serves as an articulate symbiosis of concept and space that reveals a novel dialogue between the students/staff at Spelman and the Black women in the images. They are mirrored reflections of each other. In Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation, the power of documentation is uncanny. Present reflections and past echoes are wielded to capture the deeply engrained yet often elusive radiance of Black women in America.

Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation is a participatory exhibit. Viewers must slide their fingers into a pair of white, cotton gloves before entering the museum. At first glance, the walls bear large format black-and-white, and color photographs of bright eyed models and fashion figures. However, Black Image Corporation is to be experienced (it’s what the gloves are for). Bespoke shelving, housing hundreds of framed photographs, are set in the gallery for self activated engagement. Atop each shelf is a display surface where visitors can further examine photographs, swap them out, or even leave vacant for a following guest.

Participants are also curators, having the agency to organize or reorganize photos for themselves or those to follow. Category codes—Entertainer, Everyday People, Female Impersonator, Model, Mother and Child, Professional—act as the images’ only identifying guide. Codes are listed with the expository text on the wall or on the back of each frame. A degree of labor is required to retrieve and behold, as cabinet configuration requires participants to bend and nearly kneel to access the photos.

The display surface is at lectern height, but the shelves are waist and below waist level. One must bend and reach to raise each frame for view. Wearing white gloves and repeating this action imparts a feeling of veneration or service. Be it directly or indirectly, there is an evocation of, or an exercise in devotion to, the sacred feminine.

Spelman Museum hosted a conversation with Daisy Desrosiers, the Associate Curator of Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation; she recounted someone referencing the gloves parallel to white gloves worn by church ushers. Essentially, the white gloves serve a practical purpose, to protect and preserve the photographs. Alternatively, the gloves are a reminder that these images, the women and the history they represent are precious. They are to be handled with care and reverence.

Within the framework of the listed categories are hundreds of images that may have been used for Jet Beauty of the Week or The Week’s Best Photos, but there are also numerous images of the reverse sides of photographs. They are peers to the others, framed in the cabinets, but are visually abstract and initially puzzling. Numbers, letters, lines and arrows scribble the white photo surface. These notes were part of the editorial process and rarely seen outside of photo labs. Here, they give the eye an unexpected pause.

The show also includes a light box and video. The light box holds several, transparent and marked contact sheets. Magnifying glasses are within reach for viewers to have a closer look into the matrix of the creative and editorial process. By including the reverse sides of photos and contact sheets, Gates slides back the curtain to expose in-depth aspects of image production. The video features pan-shot, vintage footage of Johnson Publishing Company’s original office in Chicago. Gates is pushing for a holistic narrative of this enterprise by including these elements.

A banner of Black culture, Ebony and Jet anchored images of Black excellence, stardom and beauty. The physical magazines were standard cultural currency in Black spaces. Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation exposes an understanding of the exceptional story the images from the archive tell. Gates’ intervention revives and ushers a specific vision: his own.

He owns rights to the Black Image Corporation images and in selecting them; they are entirely of women. The overarching role of the male gaze has been the center of much art historical static. The debate is relevant here as well. As owner, how will Gates handle these images of women in the years to come? What afterlife or rebirth exists for them? It’s safe to assume the extraordinary spirit of Black women inspired this work from the moment the photographs were taken to the existence of Theaster Gates: Black Image Corporation.

Gates: Black Image Corporation is on view at Spelman Museum of Fine Art from January 28 – May 16 2020.