We stand on the shoulders of giants, real people more god than man who persevere despite unfathomable odds. They put it all on the line for the whole. So many become martyrs: give their flesh and blood in pursuit of something greater: humanity, an end to legislated inequity and a path paved with more opportunities for generations yet born.

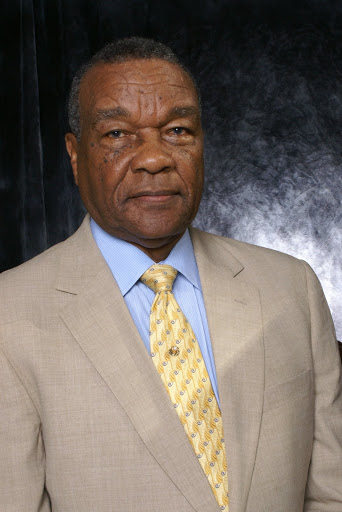

David C. Driskell was born in 1931, in Eatonton, Georgia at the height of the Great Depression. His lot was consecrated in the sweat and endurance of his forefathers. His paternal grandfather, William Driskell was born into slavery in 1862. With only a third-grade education, William Driskell taught himself doctrines of the Methodist faith and eventually became a minister. His son, George Washington Driskell was born free, completed primary school and later became a Baptist minister. Though they lived modestly in Appalachia in western North Carolina, the Driskells believed in the power and importance of education.

Driskell dreamed of becoming a great artist and ventured to the Mecca, Howard University, in the early 1950s to pursue his studies. While there, James C. Porter, a distinguished scholar, pioneer and founder of Black art history, adopted him as his protégé and encouraged that his studies also include a thorough review of art history. ”You have a good mind. You can’t just be a painter,” Driskell recalled Porter telling him early on. “… We need people to help tell what we have done.”

Driskell heeded Porter’s advice. In 1953, he was granted admission into the elite Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. In 1962, he graduated with an M.F.A. from Catholic University of America. By the end of the 1960s, many of the dreamers and activists who fought alongside Driskell to end varying forms of racial discrimination had been assassinated, Dr. King, Minister Malcolm, the Kennedy brothers and Lumumba, gone.

America had won the space race but struggled to enact lasting protections for its non-white citizenry. In 1969, Samella Lewis founded Concerned Citizens for Black Art. Audre Lorde published her first book of poetry. But academic canons continued to buck against inclusive histories that decentered white-cis-male discourse. At this time, only three scholarly texts were widely accepted as critical compendiums about Black contemporary art: Alaine Locke’s seminal work Negro Art, published 1933, Porter’s benchmark Modern Negro Art, originally published 1943 and reissued with an introduction by Driskell in 1969 and American Negro Art, an obscure work by Cedric Dover published in 1960.

In 1976, in partnership with Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Driskell curated Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950, a formative exhibition of more than 200 works that honored the artistic achievements of 63 Black artists. The exhibition was a defiant rallying cry that set a new precedent for Othered scholars and marginalized artists to refuse erasure.

The next year Driskell joined the faculty in the Department of Art at the University of Maryland College Park and remained there until his retirement in 1998. During his tenure, he authored and edited innumerable publications, including the monumental seven-volume compendium, The David C. Driskell Series of African American Art, and curated scores of exhibitions that canonized and validated the work of contemporary African American artists. In 2001, The University of Maryland established The David C. Driskell Center to acknowledge, conserve and sustain his extraordinary legacy.

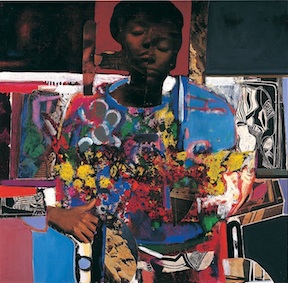

Driskell’s prolific, multi-discipline approach stands as an uncompromising monument to Black creative genius. During his illustrious academic career, which spanned over 60 years, Driskell painted hundreds of visual works that included figurative and abstract explorations. His legacy challenges us all to walk confidently and diligently in our purpose.

Driskell’s determination, brilliance and passion to revise and diversify the field of art history lives on in us, a new generation of artists, writers, and curators. We are compelled to continue his audacious decolonial work so that those who come after us will never have to experience the devastating hypocrisy of a singular, non-inclusive history.