Currently on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts is Delita Martin: Calling Down the Spirits on view until April 19, 2020. Below is an excerpt of a studio visit with Delita Martin, featured in issue 4, volume 1 of Sugarcane Magazine.

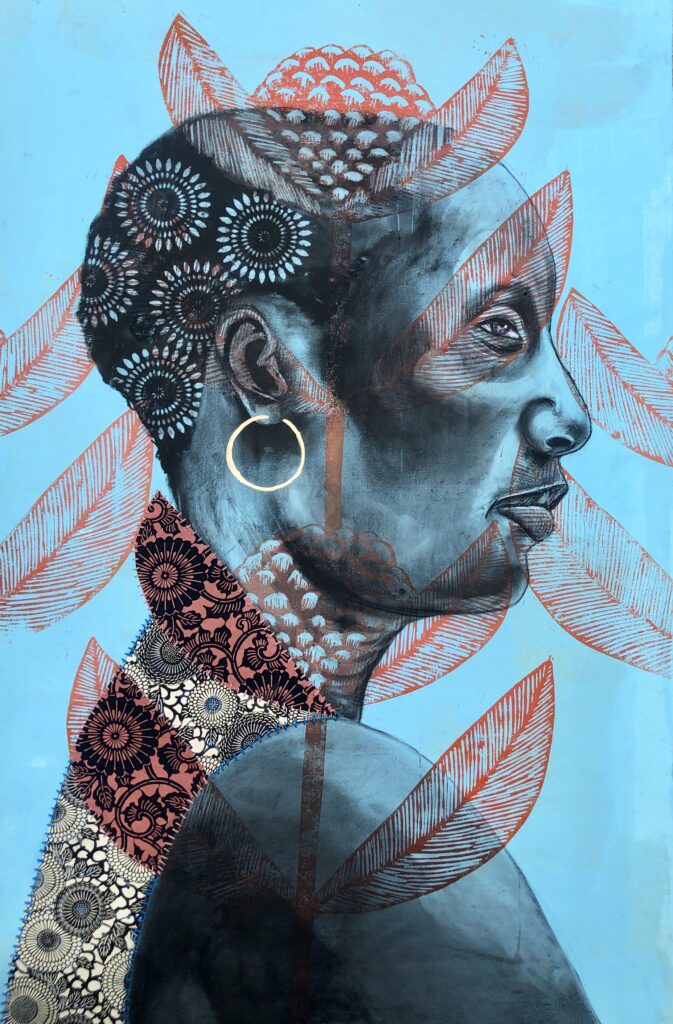

Above: Delita Martin, New Beginnings (detail), 2017; Collection of Sheila C. Johnson; Photo by Joshua Asa

“I want to create magical realism,” says Delita Martin as she leads me into her studio. It is a large space, every corner filled with tangible magic. My eyes scan over hundreds of printing tools, paints, stored art work, fabrics, vintage dolls, and finally rest on a monumentally large piece of work that the artist is still in the process of finishing. There, we both pull up a chair, discuss the magic that fills the room and unpack the imagery before us.

“I’ve been interested in making very large work for a long time now, and I finally realized that I just really needed to do it,” Martin says, while noticing my eyes enlarge, while viewing the work up close, totally in awe of the scale and meticulous details.

“It’s different seeing my work in person isn’t it?” she asks, as if she is reading my mind.

Martin’s work is so intricately layered that the most sophisticated camera cannot capture the experience of an in-person engagement. The in-progress work is approximately 12 feet by seven feet. This scale was not predetermined; Martin does not plan out her imagery before she begins working—it all happens intuitively, while she is in the studio, in the process of letting an idea manifest on its own, as she allows the idea to lead her in the process of making.

Martin’s figures are usually solitary portraits, but she wanted to challenge herself with this current work by creating a composite portrait of six figures, two are seated and four are standing. The scene is a conclave, a secret meeting of women transitioning, communicating in, and communing with the spiritual realm.

Though there are multiple figures in the composition, the subjects stand alone, engaged with each other and the viewer simultaneously. The figures are women of Martin’s family, her mother, her niece, her sister, her cousin. Scale performs a large part in the ways the viewer is able to participate in the clandestine spiritual meeting, and leads one to question, am I the viewer or am I being viewed?

Throughout the work, there is a Trinity reference. No matter how the image is viewed, the composition can be divided by three elements: the spiritual, the physical, and the transitional. One of the most prominent aspects of Martin’s work is the way she captures the visage of her subjects. Martin renders her work by hand, using both memory and photographs to develop emotionally evocative expressions.

“I am not interested in creating portraits in the traditional sense, I want to capture the spirit of the individual, not just the interiority that is represented in this realm, but I want to draw out the essence of the person, and show who they are within the spiritual realm,” says Martin.

She admits that the search for her own identity within a spiritual context has been a guiding force in her artistic practice, and the work she creates helps her to develop this inquiry further.

“A shift happened when I moved back home to Houston in 2013 (after being away for several years),” she explains:

I don’t feel the need to make work that is hyper-realistic anymore, there are images that I’ve created that don’t actually look like the person, but they feel like that particular person—and that’s what I’m interested in. The first time I did a portrait of myself interacting with a spiritual figure was very powerful; I felt it.

Just creating the work and seeing myself with this figure that I knew came from the spirit realm, and how we interacted together was a powerful moment. So in the piece I’m working on, I wanted to experience what the women I connect with, women I know, women I love, would look like during this transitional moment of connecting within the spirit realm.

The large-scale piece in progress will remain untitled until the work is completed; Martin waits for her pieces to name themselves. She explains this surreal interaction:

I never feel like I name or title the work I make myself. It’s always a spiritual conversation. I was working on this one piece, a portrait of a woman, and the woman started to speak to me. I asked her what her name is, and she said, ‘My name is Rebecca. It means to bind.’

So not only do the subjects I create give me their names, but they also give me the meaning of their names. This is the type of interaction I have with my work while alone in my studio—strange and supernatural things happen—I’ve gotten used to it,” she laughs.

Delita’s husband explained over dinner that the family has gotten very accustomed to the way she engages with her work, and they support her spending hours, sometimes days at a time, alone in her studio.

Martin constantly engages with the work of fellow artists, past and present.

The large work-in-progress was anchored on the floor by the weight of books. She insisted that she simply selected heavy books to stabilize the composition on the floor, rather than for their content. However, framing the work were books on Adrian Piper, Charles White, Wangechi Mutu, Robert Motherwell, Kerry James Marshall, John Biggers, Kara Walker and others.

These books house both images of artistic productions and theoretical practices that are aesthetically in dialogue with the formal and conceptual tenets of Martin’s work.

It was as if she unintentionally created a ready-made, metanarrative sculptural component, charged with the history of Western art, while imbuing her own work within the specific history of Black diasporic artistic production.

Her work stems from a strong legacy lead by the compositional skills of John Biggers, the draftsmanship of Charles White, the printmaking/carving of Elizabeth Catlett, and the collage/assemblage work of Bettye Saar. The seamless combining together of these elements tempts critics to label Martin as a mixed-media artist, but if you ask her, she will declare that she is, first and foremost, a printmaker. This is a very important distinction for Martin as she realizes the dying of the printmaking practice with fewer and fewer young artists pursuing the craft.

Delita Martin earned an MFA from Purdue University in 2009, with a concentration in printmaking.

During the studio visit, we continue to examine the work-in-progress before us, and Martin breaks down some of the symbols, motifs and iconography that often appear in her work. Masks are commonly used in Martin’s work, and though their designs may reference masks of West Africa, the Congo region and South Africa, it is important to note that Martin’s masks are not exact replicas of these ancient cultures.

Delita is tapping into what scholars have referred to as the Black, or African Imaginary. This theoretical practice is based on the use of African retentions, or Africanisms, the technical, spiritual, linguistic, social and creative devices that survived, and still remain, in the wake of the Middle Passage, chattel slavery, and colonialism. Martin has created her own symbology, which references historical objects and belief systems, but like Black culture within the New World, it has its own specificities.

In this scene, the seated figure wears a mask, symbolizing that she has already transitioned into the spiritual realm. She is the central figure, rendered with a visual weight that compositionally anchors the women around her. The central masked figure protrudes forward within the composition, as her mask symbolizes a conduit from the earthly realm to the spiritual realm; hence the matriarch is the leader of this secret meeting, compelling the other women to transition the way she has.

One figure offers the matriarch a bird, which for Martin symbolizes a spirit. Another, younger woman is offering the matriarch a bowl. Martin explains that the bowl represents the womb, symbolizing spiritual birth, and the intersection of the two worlds that are in a constant exchange.

Clothing becomes costume in Martin’s work, she embellishes quotidian attire with sumptuous layers that evoke feelings of wonderment and fantasy. Elaborate collars, masks, exaggerated silhouettes, feathers, beading, encrusted halos and auras repeatedly appear in her images.

“When I look at the clothing a person is wearing, I examine how I can make the clothing transition into the spiritual world as well,” Martin says. “So I push what someone is actually wearing into another space and place that symbolizes them in another way. I’m creating a masquerade, a masquerade that does not hide the identity of the person but emphasizes the spirit and the energy of the person.”

Martin’s grandmother, who was very significant in her upbringing, kept glass Mason jars and tin coffee cans full of stuff: found objects, sewing notions, coins, little paper notes, jewelry, and safety pins. At times, she would empty the contents of a jar onto her bed and tell Martin the story of each stored object, remembering and transmitting the way she acquired each object and what it meant to her.

Martin has retained her grandmother’s memory-conjuring ritual of storing and emptying materials from vessels. This has spurred Martin’s practice of associating materials with what she refers to as ancestral memory.

“I began to associate these objects with people, places and events. And I began to use these symbols in my work,” she says. “The birds started showing up, the bowls and the masks started showing up, so I realized that I was creating a language, a visual language, a language that I continuously use to tell stories within my work.”

Read more in our Black and Basel issue here.

Danny Dunson is a writer, editor and creative behind the popular Instagram account @legacybros