The Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami (MOCA) will present a groundbreaking exhibition celebrating the founding of AfriCOBRA – the black artist collective that defined the visual aesthetic of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. 2018 marks the 50th anniversary of the Chicago based collective. “AfriCOBRA: Messages to the People” will be on view at MOCA from Nov. 27, 2018 – April 7, 2019.

AFRICOBRA: Messages to the People Curator Jeffreen M. Hayes earned a Ph.D. in American studies from the College of William and Mary, a Master of Arts in art history from Howard University, and a Bachelor of Arts in humanities from Florida International University. She is currently the executive director of Threewalls in Chicago and has previously worked at the Birmingham Museum of Art, Hampton University Art Museum, the Library of Congress and the National Gallery of Art. Her curatorial projects include “Intimate Interiors” (2012), “Etched in Collective History” (2013), “SILOS” (2016), “Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman” (2018), and “Process” (2019). She was a guest curator for Artpace San Antonio’s International Artist in Residence Program from May-August 2018.

Daniel Dunson: AfriCOBRA works seemed to have reemerged within the last decade. I’ve not only seen these works within the art world, but also in quotidian spaces, public spaces, and ubiquitously on social media platforms. Why do you think the work of this 50-year-old collective has come to the fore?

Jeffreen Hayes: It’s twofold: part of it is about where we are socially and politically, and the other part is the commemoration of the 50th year anniversary of AfriCOBRA’s founding. These commemorative moments come to the fore because we realize that though times have changed that we are still not very far from these historical moments. We are in a moment where we are trying to rewrite and expand art history to include those who have been overlooked in the mainstream art world. AfriCOBRA is still very much an active collective, so it’s more about the art world catching up to the work of a collective that has been ahead of the curve.

DD: The art world also seems to be getting away from using terms such as “outsider art.” The barriers between who is inside and who is outside are seemingly collapsing.

JH: I agree with that. I think this also is in tandem with newer scholars to the field, and younger curators that can push and collapse these boundaries in a different way than in the past. I also think there has been a shift in visibility for Black artists in the contemporary moment where some of the work is entirely collapsing these boundaries. Now dealers, museums, and art historians are having to wrestle with that, and think about how our society is shifting- the demographics are changing every day. How can the art world and institutions that shape the culture, keep up with these changes? How can they be relevant? I think this where AfriCOBRA comes in, and why we are revisiting them and giving them their moment.

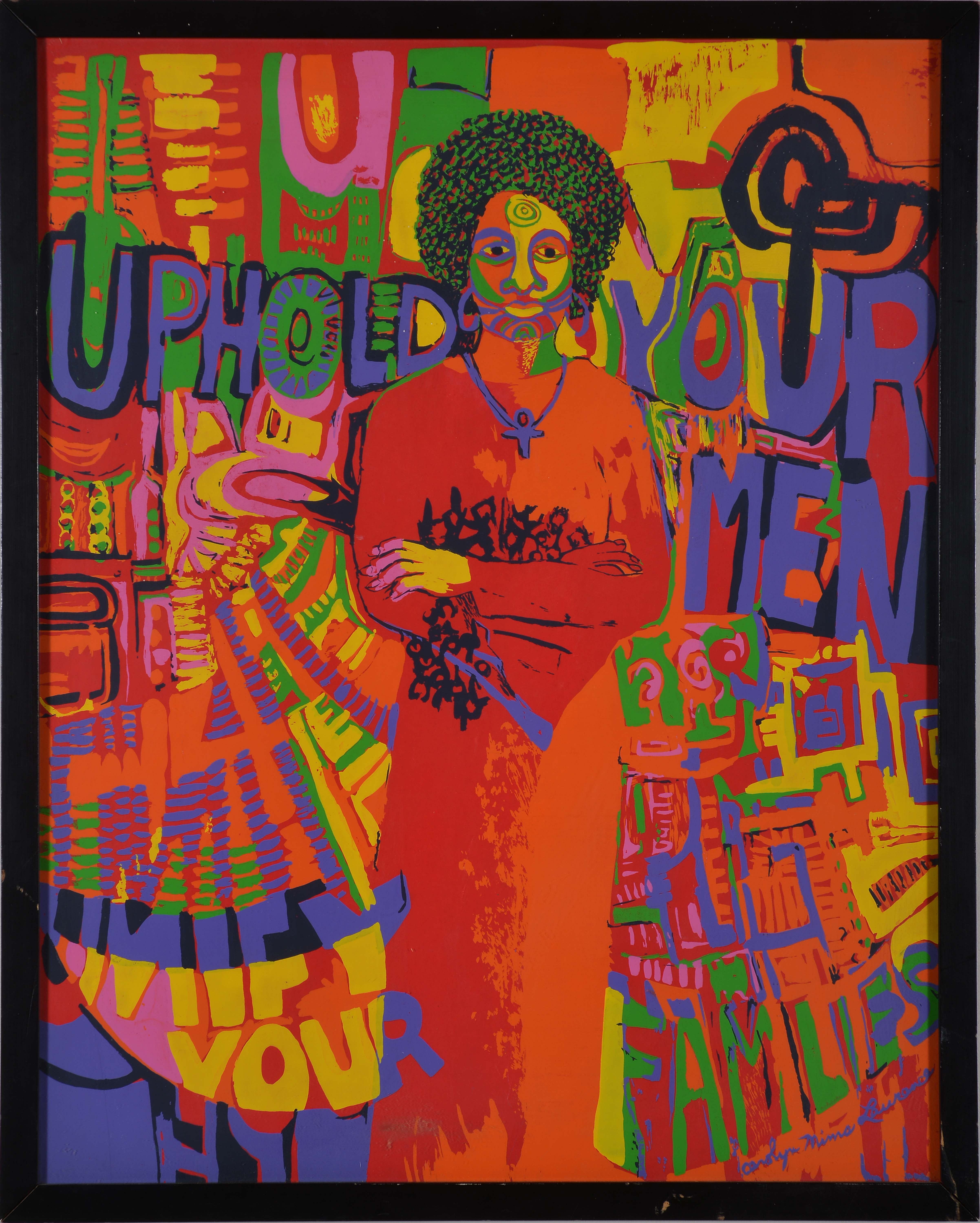

Above: Carolyn Lawrence, Uphold Your Men, Unify Your Families, 1971.

DD: Tell me about your connection to the work. I have a feeling that this project has been a longtime interest of yours. It is aligned with other commemorative projects you have done. Your curatorial and cultural work has contributed to making large repositories of data that we can now access. This project must be of great importance to you, especially now that you are based in Chicago where the collective started.

JH: My connection to AfriCOBRA started while I was at Howard University, where many of the collective’s artist taught and are still teaching. I must stress the important role that Historically Black Colleges and Universities play in the field of art. Howard is the place where I got my education, a real education in Black art and the Diaspora. I was introduced to AfriCOBRA not only through textbooks but through its actual members that taught at Howard University. The introduction of Black aesthetics from my professors really helped to solidify my curatorial and cultural work in centering Black artists and cultural producers. It’s been wonderful to be in Chicago, and I’m very excited to provide different introduction and entryway to the work of AfriCOBRA that is different than what has been experienced before. It has been wonderful to see the different AfriCOBRA shows that have popped up over the past few years. In my curatorial practice, I always consider origins and beginnings, so with this show, I’m thinking about the work of the early founding members of AfriCOBRA (Jeff Donaldson, Jae Jarrell Wadsworth Jarrell, Barbara Jones- Hogu, and Gerald Williams). I’m bringing these early works together in this show to make a statement about how these works are the antecedents of current artwork and cultural productions. It was imperative to my curatorial practice to think about the impetuous of this collective because we often don’t study the beginnings, often we look so far ahead that we forget where we came from. That’s the reason why much of my curatorial work deals with the pioneering artist. I just completed a project about Augusta Savage, a woman artist of the Harlem Renaissance, and I have been thinking about how Savage, like the artists of AfriCOBRA, was created spaces for Black art, educating students on Black aesthetics, and being a part of collectives. I feel it is very important to think of Black art as a continuum that is in constant dialogue with this past, to make sense of Black artistic productions of today. With Black art, I don’t think we can have a present or future without engaging with cultural productions of the past. A lot of people, even some contemporary artist of today, do not know this history, which is why it is so important for me to be doing this show in this way.

DD: I appreciate that you are pinpointing the presence and contributions of HBCUs because for many years, and perhaps still now, it was the only place to receive a certain kind of education–an education that brings Black art history to the fore. I feel that the past conversations around AfriCOBRA’s work are still relevant today and agree that Black art is on a continuum. The dialogue that work presents shifts and acquires different attributes that are relevant to its time, but never steers far from its root. Black art right now is receiving a lot of commercial attention, and I steer away from using the term “trending,” but there has been a shift in the art market, and institutional exhibiting.

JH: AfriCOBRA was very intentional about their work being accessible and reproducing pieces so that anyone could access them. That was important at that time because they were making work for Black people, they were educating Black people, that is who they were speaking to. They weren’t concerned with the market; they weren’t concerned with critics. It was really about the people. Today in the contemporary art world there are some people who want their work in homes, and I think there are more people who want to engage in the art market. Many artists want their work in important private collections and major institutions. I think the market is dictating that desire, more so than making sure that everyone has access to their work. However, I don’t fault these artists, because there is a market for their work, and they must sustain their practice! I think we tend to forget that these artists are also human beings who have lives, families, and experiences just like the rest of us. They must sustain themselves. At the same time, I do think that art should be accessible to everyone. Maybe it’s not necessarily about the artwork being in the home, but it’s about the people being able to experience artwork in the most accessible and welcoming way– sometimes museums and galleries are not that place. I am interested in artist doing work that is made for the public, to balance out the desire to be in collections. Being in these collections is still very important because they are the repositories, but it’s important also to find ways to balance art’s accessibility. I also believe that art should be for the people. So how do we adjust this? This issue presents an opportunity to support and sustain practices of emerging artist and even mid-career artists whose work is not selling for tens of thousands of dollars.

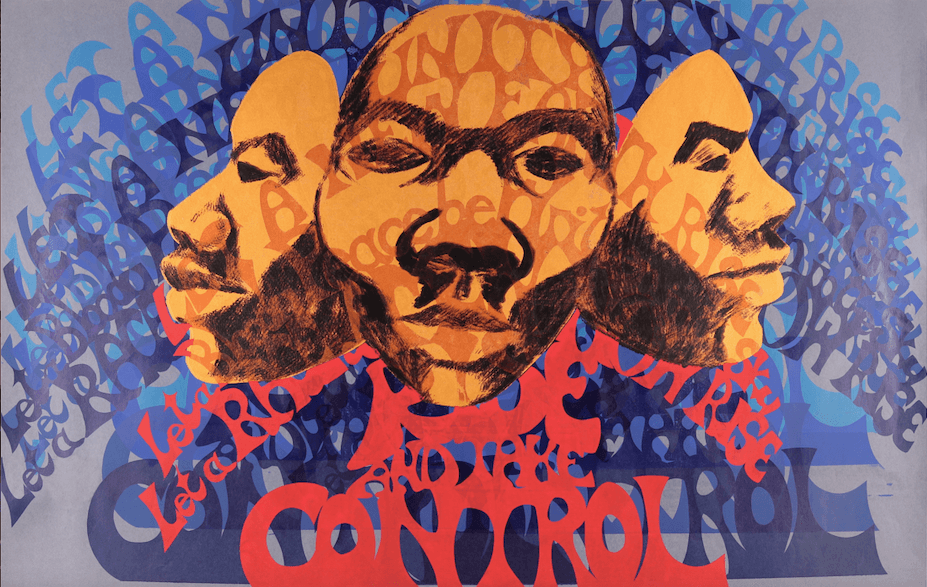

DD: I was at the closing reception of the AfriCOBRA 50 exhibition at Kavi Gupta Gallery in Chicago. I was so happy to engage with founding AfriCOBRA member Gerald Williams. Williams discussed his iconic painting Angela Davis (1971), and how he situated the visage of the activist within the symbolic images and text. He said that this was a direct response to graffiti art that was appearing more and more in urban spaces during the late 60s and 70s. We wanted to have a dialogue with text imagery that was gaining more and more momentum. I found this to be incredibly exciting because it was a concept that is in conversation with the canon of Western art history. Immediately I thought of Dada and other art movements that used text imagery in the pictorial plane. Then I thought of the work of contemporary artist Glenn Ligon and others who use text in their arts practice, and how this visual trope is also on a continuum. Why do think this trope has remained relevant in contemporary art? What are the cultural implications of creating art with text imagery?

JH: So, this is a very interesting question in terms of social media, especially Instagram, because I find is that the body receives many more likes than images of text. If you just look at anyone’s account that has images of text rather than images that reference the body, you will see that they have fewer likes. I think the use of text within contemporary work is still prevalent because it’s easily recognizable. If you have never been in an art museum and you come across a nonrepresentational abstract work, and a work that includes text, chances are that you are going to engage with the work with text more readily and easily because it is something you recognize. I think it is an interesting trope to use to seduce the viewer into looking and spending more time with the work. I think many of us are just hardwired to read something, and the text breaks down that barrier between visual art and literary art. I also think this visual trope is important because literary works have a stronger presence within the Black Community. When I think about the Black Arts Movement and the Harlem Renaissance, typically the writers are discussed, we don’t really talk about the visual artists. Part of it may also be tied to our history as a people. Black people were not, to put it nicely, encouraged to read. I think we are tied to the written word, in a way that others may not be, due to our history.

Above: Barbara Jones Hogu, Rise and Take Control, 1970.

DD: So now I am thinking about cultural memory, and this may be corny, but I am thinking of the film adaptation of Alice Walkers’s seminal novel The Color Purple (1982), and how the main character Celie is learning how to read from younger more educated sister Nettie. Nettie places large scraps of paper with text on items the items that words represented, so her sister to expedite the learning process. So, I wonder if the use of text in much of AfriCOBRA’s work was a sophisticated way to create visual literacy within the field of art. This trope knocks down several years of educational disenfranchisement, and it works to close the gap for black art viewers who were not able to take decades upon decades of art history coursework. The text in the images forms a shorthand discourse to lead viewers to the import of the work and facilitates further independent visual analysis.

JH: This is where we connect back to Gerald Williams point about graffiti. Text can be used as a tool for visual literacy, especially since we are talking about visual art being deployed in public spaces and used as a tool to educate young children. AfriCOBRA was profoundly instrumental in that way. These artists used text so effectively in their work that the image was able to be empowered with its use.

DD: Is there a work in this upcoming exhibition that you feel transcends time, and is most relevant to the social and political climate of today?

JH: Well, there is more than just one!

DD: Oh great! Even better!

JH: There are a few that come to mind. In the show, we have Sherman Beck, who was an early member of the collective. He left the collective in about 1978, but he was included in the first AfriCOBRA show. When I did a studio visit with him, he showed me work that was in progress, and there is one work that we have included in the show. While this work is connected to the past, it’s also strongly linked to the present. It’s called Till Proven Innocent, a painting based on the Scottsboro Nine (Nine African American teenagers, ages 13 to 20, falsely accused in Alabama of raping two White American women on a train in 1931). And when I saw this work, I thought wow, although we have grown as a country, we are still in the place where black bodies are always under fire. Though it’s hard for us to pinpoint a specific date on this piece, because Sherman continues to work on his paintings over the years, I feel that this historical moment is relevant to today and I’m happy it’s in the show. The Angela Davis painting by Gerald Williams is going to be in the show. This painting is relevant because of the important concepts of liberation, organizing, showing Black women at the forefront of leading change.

DD: This my last question. We have talked a bit about Black women in the arts. How important was the presence of women artist, Black women artist of the AfriCOBRA Collective to the Black Arts Movement?

JH: Really important! Their presence helped to balance out what was happening politically and artistically. I don’t think that as a Black woman curator, administrator, cultural worker who values Black women’s contribution to the arts, that you can have a movement, whether artistically or politically, without black women. And Black women remain at the center. What I love about AfriCOBRA is that it was founded with two black women. That’s very important to emphasize because black women were not always included in the founding of art movements and collectives. It was so important that Jae Jerrell and Barbara Jones Hogu were instrumental in the founding and played an equal role with the men in the group. Having Black women be a part of the story is just as important today as it will be in the future. These women contribute just as much, and sometimes more than the men It will always be important to uplift these women and remember their names in the narrative.

*AFRICOBRA: Messages to the People is made possible with the generous support of Miami MoCAAD, Miami Museum of Contemporary Art of the African Diaspora. Additional support is provided by Lehman Autoworld, Kavi Gupta Gallery, and Audi North Miami. The forthcoming catalog is made possible, in part, by the Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation. MOCA’s exhibitions and programs are made possible with the continued support of the North Miami Mayor and Council and the City of North Miami, the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs and the Florida Council on Arts and Culture, and Miami-Dade County Tourist Development Council, the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs and the Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County Mayor and Board of County Commissioners.