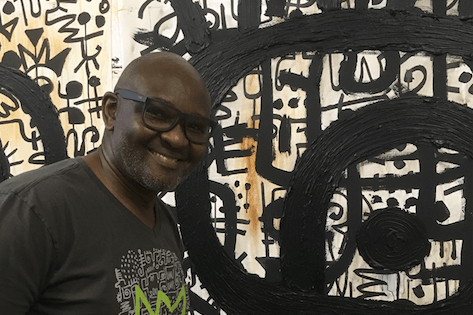

This past April, I met painter Victor Ekpuk (Nigerian, born 1964) after his presentation and panel discussion at Howard University’s Porter Colloquium, a Black art conference. During April and June, I sat down with him to discuss the roles of image and rituals, and how they related to colonization, slavery, and eventual freedom.

Also, we thought about how creating artistic content could serve as a connection to a higher power. Ekpuk’s usage of pictorial writing and spiritual inspiration forms a large part of his process “drawing memory”; over the course of his career, his artistic output evolved into different forms and figures that explore space, color, and time.

Below, I have written an incredibly condensed transcript of our two conversations: Mr. Ekpuk participation in the 2018 iteration of the group show Resignifications, Victor’s installation in the 2015 Havana Biennale, and his ongoing research with the American slave narratives.

Lyric Prince (LP): How was the group show, Resignifications?

Victor Elpuk (VE): Resignifications is an ongoing series with the theme of Black portraiture or Black representation. This year, Resignifications was in Palermo, Italy, looking at the issues of immigration and historical contact within Africa and Europe.

LP: I saw the overview of the show on Instagram, and there were pieces by Fabrice Monteiro, Delphine Diallo, along with installations by Maimouna Gueresi and Lina Iris Viktor, and others. With that group of artists, how did you feel you fit in?

VE: Awam Amkpa’s curation of the exhibition brought different kinds of work with different expressions- that of identity, social commentary, or just political issues that artists thought to bring. If I recall correctly, the curator divided the exhibition into four different sections: the historical part, which showed the Eurocentric representation of Africans in the Renaissance period; then, the second part of that exhibition was Africans’ response to that history. Then, the third part was to show how Black artists focused on making their own visual culture, free of European influence. The other section concerned spirituality, and that is where the curator added my work.

LP: What other events surrounded the show?

VE: Apart from the exhibition, there were lectures and moderated panels. A number of important scholars, such as Nobel Laureate for Literature Wole Soyinka, Paul Gilroy, and Ian Chambers presented papers about the issues within the African Diaspora, particularly with the migration of Africans across the Mediterranean.

Above: Victor Ekpuk-Meditation on Memory Havana.

LP: I think that the scholarly aspect is so important to put in context along with the art because otherwise there’s a tendency to say that it’s just beautiful, or decorative. Regarding spirituality and your works in Palermo, how did that reflect upon your installation for the Havana Biennale in Cuba a few years earlier?

VE: Well, my work generally explores the human condition and spirituality, and Cuba was really about engaging that. My intent for the Havana Biennale project was to create a sacred space to honor my ancestors who were taken to Cuba and whose memories still live on in the Diaspora. My work is inspired by writing systems, spiritual symbols called nsibidi- and I call this process of using them “drawing memory.”

For the performative drawing installation Meditations on Memory, I invited the local members of the Abakuá religion to come in and perform rituals in the space while I drew the signs on the blank walls, transforming them into an Abakuá lodge. The signs that I marked in white chalk on the walls and floors were also tattooed on the bodies of the young men I befriended in Havana. It’s not just their religion, it’s their personal identity. The color and use of white chalk were very significant in this particular installation because of its symbolism and how it marked ritual spaces, which are descended from the inner sanctuaries of meeting houses or lodges of the Ekpe (Leopard) society in Nigeria. The work was ephemeral and was eventually erased; it was never meant to be permanent.

LP: With your work exploring this Indigenous or pagan religion, are you making a conversation between it and the religion that had a role in enslaving us- Christianity? By connecting your piece The Union of Saint and Venus with Dum Diversas, you seem to be making a direct critique of Christianity’s role in the transatlantic slave trade.

VE: Not necessarily. I’m acknowledging Indigenous African spirituality and its belief in God, or Gods- which is not Christianity or ‘paganism!’ (laughs) The Union of Saint and Venus is part of a series of works, called “Slave Narratives,” which I am currently researching for my artist fellowship at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. I’ve been doing work for this series since 2007. My focus is on the history and expansion of transatlantic slavery, and I regularly look through the museum’s archives to find imagery and personal narratives of the enslaved. I aim to use the materials and information gathered in this research to continue creating a body of paintings, drawings, and sculptures that explore the tragic experiences of enslaved Africans, and to develop alternative visual narratives.

The first piece in this series, Slave Narrative 1, is now a part of the permanent collection at the National Museum of African Art. With The Union of Saint and Venus, there are symbols- the Black body, in the shape of Sarah Baartman or Hottentot Venus, which represents what was taken from us; the pope’s golden crozier (phallic staff) pierces her body. And there’s another part, which is very important– the hat. That’s where the real story is. Inside, you can read the text of the Dum Diversas, a papal bull by Pope Nicholas V which made slavery into law in the New World. So, from afar, you can see this very nicely decorated hat, really glammed up. But then, inside, is the ugliness of it.

Above:Victor Ekpuk, Union of Saint and Venus” 41”x71” (106cm x 182cm), acrylic. Photo by the author.

Above:Victor Ekpuk, Union of Saint and Venus” 41”x71” (106cm x 182cm), acrylic. Photo by the author.

LP: What do you think they had to do, to justify this in their own eyes, to make that okay? To make people into animals?

VE: First, you make it into ‘God’s’ edict. Then, you label people as primitive, pagan and unchristian, and you form a crusade to ‘civilize’ them “In the name of God”; if they resist, you rape and murder them. “In the name of God” is always a very convenient excuse for genocides, slavery, and barbarity.

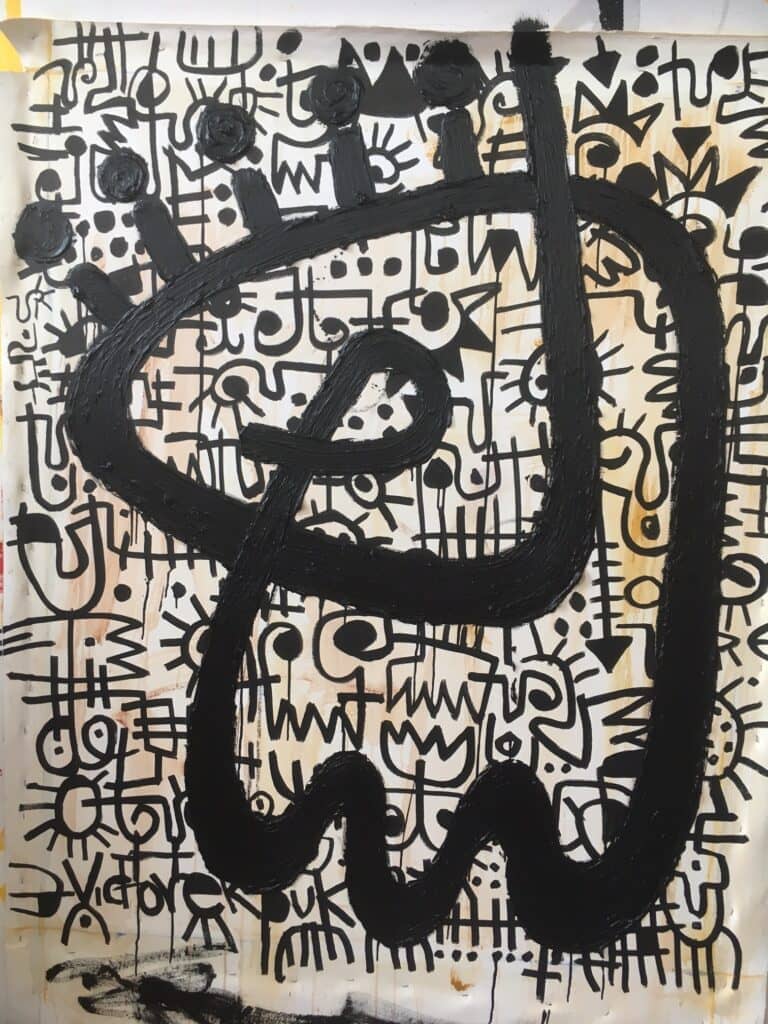

LP: I get it. Anyway, what are you doing right now, on the wall of your studio?

VE: My works are going more and more abstract, and I’m exploring my lines for their own aesthetics, rather than for what they mean. I don’t have titles for them, because I don’t think I need to.

LP: Titles are overrated! (laughter)

VE: So, I’m getting more and more interested in 3-D and looking at my drawings as 3-dimensional objects. What I’m trying to do on the canvas is bring the lines out, almost mold them on the canvas as sculptures.

LP: Fantastic. Let’s look at these two on the wall…You have the smoothness of the lines, and the background wash is in an earth tone, ochre. And there are thin strokes alongside the thick and heavy layers of acrylic paint, built up with different textures. They feel like a relief sculpture. Are they finished?

VE: These paintings are finished, but I’m waiting for them to dry so that I can put another canvas on. I want to make a series of five or six before I stop.

LP: So, I think of the word, activist, and how it applies to what you do and how you describe the role of symbolism in your art. For me, the way you embrace your origins and doing what you do as an artist is a form of activism.

VE: Due to the way that I draw from my culture, I don’t feel like I have to put the title of ‘activist’ in my name. I defend my aesthetic from being consumed by Western narratives- which I guess is a form of activism, in a world where you are told to think differently. Western culture and art history are assumed to be the beginning and end of all human experience, so I make it a point to assert that there are other cultural narratives that are older. Mine, which is African culture, is one of them and I can tell you why. It’s me being able to respond to someone who says, “Your work looks like Miro…”

LP: But wait—Miro borrowed from you! (laughter)

VE: And then I can say—No, it’s not. This is what it is. And I’m not going to shy away from telling you what the facts are. Hopefully, some will expand their consciousness.

Above: Victor Ekpuk, Untitled #1. Photo by the author.