For the majority of history, our political leaders have doubled as icons, held sacrosanct instead of being portrayed realistically. We see this illusion, for instance, in the numerous state portraits of Elizabeth I, with the white face and richly dressed form of an eternally Virgin Queen, solely dedicated to the welfare of her people. In the case of Barack and Michelle Obamas’ official portraits in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., they present two distinct interpretations of blackness. The styling, execution, and mere presence of the portraits created by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald in the galleries themselves demonstrate the much-needed hope and innovation that America was once known for. Visitors from all over the country came to the 11:30 opening of the museum, and witnessed the first time the portraits were displayed to the public.

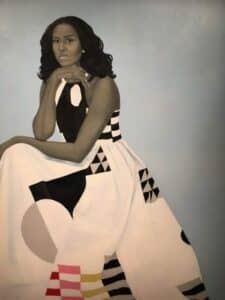

The composition of the Obamas’ bodies on canvas contains exceptional order and structure, where geometry and symbolism play a central role. The First Lady’s portrait is composed with triangles- the shape of her figure in the painting forms a mountain of body and quilt like dress placed in the midst of a powder-blue sky, leading up to the summit of her face. Many casual reactions online have also said that there is no strong likeness in her portrait; this could be because of Amy Sherald’s characteristic use of grayscale skin tone, as well as the stylistically elongated and pointed shape of the First Lady’s face. However, when one examines the painting closely, another triangle emerges from inside of the face- amid all of the other parts of the painting, which look like it was done without specific reference to Mrs. Obama’s body. There emerges a perfect likeness, particularly in the eyes, brow, nose, and the slight curve of the mouth, that peeks out and looks back at you, almost as if it’s looking from over a windowsill. That fleeting likeness is like an optical illusion, a style that is referenced in the shapes within her dress- where, if you blink, you miss the magic that makes the picture vibrates with life. The brush strokes, precise yet seeming to melt into the hazy blue fog of the background, lends even more mystery to a seemingly straightforward portrait of a woman that everyone knows, but never can truly see.

Above: Images of FLOTUS Michelle Obama’s portrait by Amy Sherald. Photos by Lyric Prince.

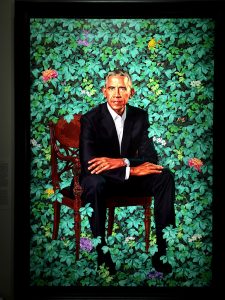

President Obama’s figure, in contrast, is formed with squares and rectangles- you see this in the chair shape, his posture, and even in the outlines of his face. He is almost lost in the bushes, so to speak, of Kehinde Wiley’s vibrant, pattern-like ivy vines and richly detailed flowers, focusing on the president’s softer and symbolic side. In particular, the modernized language of flowers is strongly featured in this composition, but not arranged in Wiley’s usual background repetition. There are three flowers represented, seemingly placed at random, besides the obvious reference that the ivy makes: the flower closest to Obama’s actual person is jasmine, which signifies his birthplace of Hawaii; the blue lilies placed at his feet and above his head are in memory of his Kenyan ancestors; and the flower that sits right next to him and floats all around the space of the portrait itself is the chrysanthemum, the official flower of Chicago. Additionally, the Federalist-style chair that Obama sits and leans out from was popular during the very first years of the United States. Its usage suggests a legacy of American style, as well as the very closest thing our republic can have to an ancestral throne; the inclusion of such an element is a relatively subtle iteration of Wiley’s signature elevation of African Americans to the pictorial level and importance of Western royalty. The hands, feet, and crouching posture appears to force itself past the foreground of the canvas in stark contrast to the First Lady’s more ethereal presence, which only seems to be anchored by the bottom half of the canvas. Obama’s face, the focal point of the composition, has the shine and gravity of a bronze statue; in contrast, the First Lady seems to glow from within- and no reproduction can do full justice to either one.

Above: Paintings of POTUS Barack H. Obama by Kehinde Wiley. Photos by Lyric Prince.

There were long lines of people at the opening, which wrapped the inside of the Portrait Gallery’s walls and out of the door of the museum, all waiting to see the personification of hope. Once face to face with it, admirers would periodically reach up to take a fleeting cell phone photo, perhaps creating a symbolic lifeline that can pull them out of a troubled sea.

If the visit to the Portrait Gallery has demonstrated anything, it is this; the Obamas’ faces are, for better or worse, no longer their own. These images reflect the hopes of a public weary of white supremacy and the mundane, and who gladly welcome people of color into the ivory halls of presidents and First Ladies for the very first time. Their inauguration in 2009 broke attendance records; it would not be an exaggeration to say that the portrait unveilings, nine years later, managed to do the same thing.

One interesting detail, however, serves as a visual challenge to the legacy of the first Black man in the hall of the presidents. His portrait is placed high on a standalone wall, facing an exhibit that celebrates the workers of America. On the other side of that wall, a small portrait of Ronald Reagan hangs in the middle, smiling and winking behind Obama’s back. In the meantime, Mrs. Obama’s portrait sits peaceably along with the other paintings in the hallway downstairs, facing the museum’s front door.

The portraits will be on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. from February 13th. Barack Obama’s portrait is located in the Presidential Hall on the third floor; Michelle Obama’s portrait is located on the first floor, adjacent to the museum’s visitors services desk.