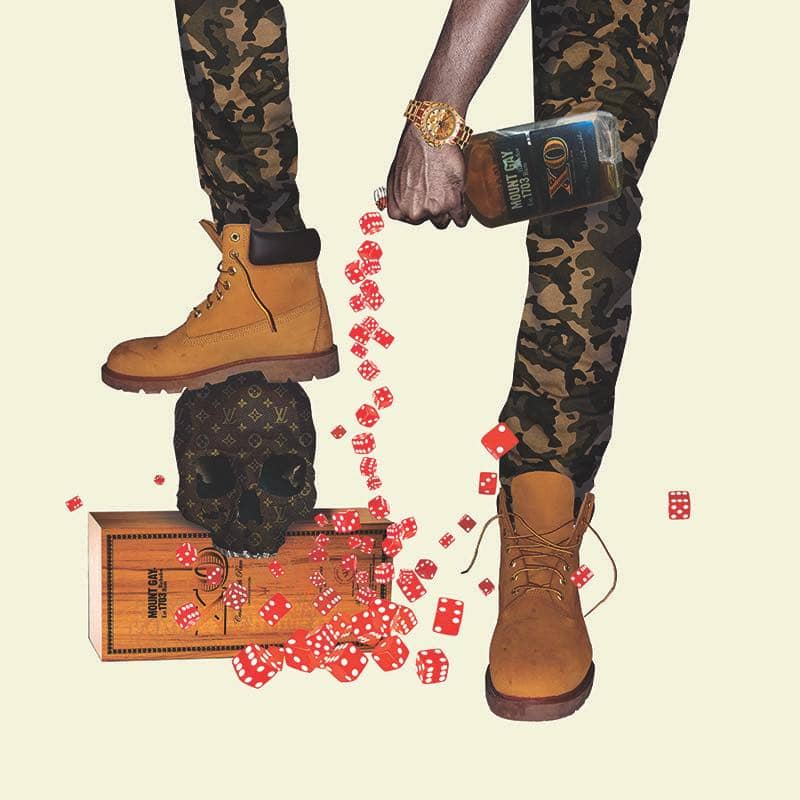

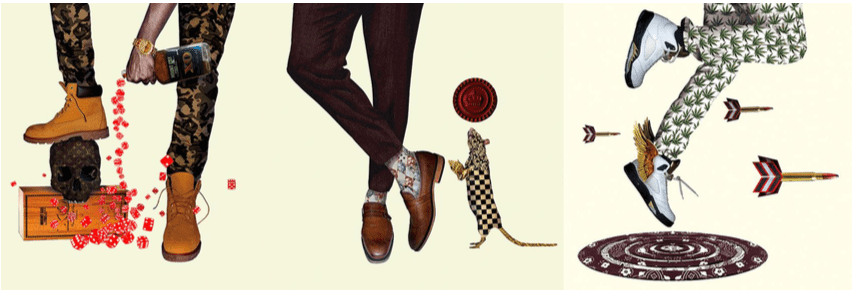

Above: Ronald Williams, Shoe Game #1

From the nigger yard of yesterday, I come with my burden. / To the world of tomorrow, I turn with my strength. 1

Here we are called upon finally to know ourselves, and here before us stand splendour and hope. […] This land, our land, can only be what we want it to be. 2

The sound that never leaves you is Bridgetown – the endless scraping surge of sirens, revved engines, the wailing horns of ZR vans and an alternating drawl of Bajan slipping through the traffic’s cracks of silence – the stretch of River Road is continuously unwinding itself in a satisfied perpetual yawn. Within the airy, exposed cinderblock foundation of Sheena Rose’s studio (now, exhibition space), that sound is ever present. A space, unfinished, or, rather, a space in development or flux, exuding a certain fluidity appropriate to the unfixed limits of our own identities. This sense of being “in process” resonates throughout the works shown in “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues.” Proposed more as a curatorial experiment, rather than a show of fixed themes and subject matters, momentary curator, Sheena Rose, has collated the works of a group of Barbadian artists, in the hope of highlighting some of the creative responses to the social pressures unique to this place. Then, as a statement, the show hopes to stand as an example for future models of improvised exhibitions – with an emphasis on a desire for more spaces to house and display visual art in Barbados. Reflecting upon “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues,” an underlying thread that is concerned with the collective conflict of Barbadian identity presents itself throughout the convergence of the works exhibited.

The Image of Black Women

I am overdetermined from outside. I am not the slave of the “idea” that others have of me but of my appearance. I move slowly in the world, accustomed to aspiring no longer to appear. I proceed by crawling. Already the white looks, the only true looks, are dissecting me. I am fixed. Having prepared their microtome, they slice away objectively pieces of my reality. I am disclosed.3

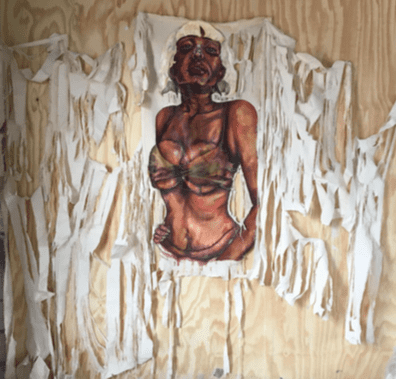

Above: Anna Gibson, Rebirth I, 2018, acrylic, wire and string on canvas, all images courtesy of the artists.

The image first encountered is Rebirth I, an installation by Anna Gibson, comprised of shredded canvas and painted layers forming the figure of a blonde-wigged black woman. Disjointed sections of her body are sewn together in distress, scarring her image as if she verges on falling apart. Her body has been transformed excessively; her silhouette exaggerated, her nose reshaped and plastered, her breasts seemingly floating, superimposed against her torso laden with stitches. This woman’s body is a site for desire, expectations, and projections. Beauty – or at least the social standards of such – cut, carve and shape her body. Being introduced to this figure, a re-imagined woman pinned to the wall to be looked at and visually consumed, realises our responsibility in regulating our ways of seeing. This figure cornered at the mercy of our gazes, our tightly held preconceptions, values, and prejudices, demands certain care in the act of seeing. It is this figure that sets the tone of “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues,” wherein which we may recognise the mutilation of our own Barbadian image, an image historically demonised, exoticised and reconfigured in varying directions and service to a multitude of gazes. Responding to these processes – to this reshaping of our bodies, narratives, and identities – the remaining works are concerned with a thoughtful contemplation and declaration of the self and a salvaging of self-image.

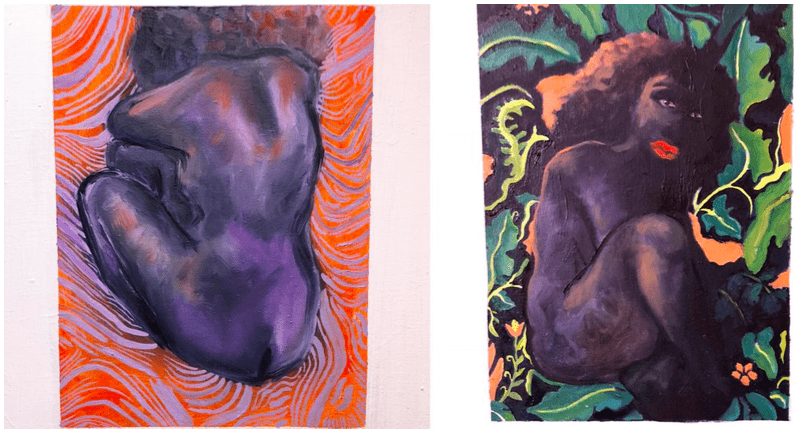

Above: Alanis Forde, Introspect: Daze (left), Oil on canvas, 2018 & Introspect: Oppressed (right), Oil on canvas, 2017

Following Gibson’s work, we encounter a different image of black womanhood in the paintings of Alanis Forde, particularly in her diptych, The Introspect Exploration. Small squared pockets of coloured landscapes inhabited by the figure of a crouching fetal black woman fit themselves in the confines of a thick painted frame of white. The figure first backs us, in Introspect: Daze, in a haze of orange and lilac ripples, and then faces us from a space of seemingly tropical flora. This woman, somewhat contained, seems to radiate these environments of intimacy outwards, anchoring herself in her own personal fortress, holding the encroaching whiteness at bay. Her posture, interests and gaze do not concern the viewer – she is meditative and disinterested from the concerns of the viewer. Her environment, here, is abstract and therefore, unfamiliar in its visual language. In her turning to face us, in Introspect: Oppressed, the environment shifts towards the familiar, introducing motifs we may relate to in nature. This shift in posture gives her bright red lips, and we recognise in her (and her environment) familiar images. Her smeared-on red lips paint her with qualities similar to those denigrating caricatures of blackness such as golliwogs, somewhat reminiscent of Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary.4 This woman, almost surprised in her recognition of the viewer’s gaze, becomes shaped to stereotypical views of blackness and black womanhood. Her formerly abstract environment betrays her in its shift to a jungle landscape, and we question whether this face is real or distorted by prejudice. Does this same caricatured face, informed by a visual history of anti-blackness, live on the backing figure, or is the truth of the backing woman’s face to remain inconceivable, forever hidden, protected from and unknown to our gaze, fear, prejudice and desire?

The Burden of the Crown

These beaches are up for grabs. The tourists say they own them. They are the ultimate frontier, visible evidence of our past wanderings and our present distress.5

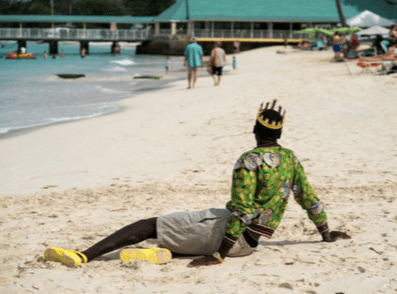

Above: Adrian Richards, That Beach Belong to We #1, Digital Print on Acid-Free Paper, 2018.

Lacking the intimate spaces of reserved comfort existing with Forde’s paintings, we encounter the photographs of Adrian Richards, where questions of black mobility in Barbados come to the surface, through the contested site of the beach. The diptych, That Beach, Belong to We (a reference to Mighty Gabby’s ‘Jack’) features a crowned black man reclining on the sands of Pebbles Beach, looking out to the image’s horizon dotted with planted umbrellas, strolling tourists and the pier of the Raddison Aquatica Resort (once formerly the Aquatic Club, a whites-only, members-only establishment in pre-independence Barbados). Backing us, the figure holds a sense of forlorn contemplation, a grieving over his lost kingdom, perched on the sand, with no planted towel to indicate a claim to space, this dispossessed black figure looks down a history of racial exclusion and exploitation, a history that bubbles in the shadow of contemporary Barbados. His crown, not an emblem of sovereignty, defines him as a colonial subject, a colonised subject, where there is as much pride in this as there is in the burnt scars of being branded as property. This is crown land, and he is crown property; part of the occupied landscape, therefore exploitable, therefore owned. The second print, horizon still affixed to the historic site of the Aquatic Club pier, faces us with a doubled image of this dethroned king, contemplating his loss, his displacement and the predicament of the land, the plight of his body. Stripped of a claim to space in his locale, he can only mourn.

Above: Jared Burton, Colourism, Acrylic on canvas, 2018

The symbol of the crown appears again in the work of Jared Burton, emphasised further as a colonial shackle. Gripping a sceptre, crowned and faceless, a mannequin-like black figure tramples and crawls over two lifeless black bodies, as seen in Colourism. A violent scene of competition and conquest, the triumphant figure is postured towards further potential domination. This stepping-over each other is indicative of the social violence particular to capitalist thought, wherein which one’s success and mobility are measured against the failure and demise of others. The crowned figure is faceless in that he is no longer of human character, doll-joints lining his skin in that he has been classed as a puppet devoid of agency. The crown, as an agent of excess and decadence, becomes a corrupt manacle by which the figure is impressed with an urge to undo his community, to rise in violent individualism over his fellow man, in spite of his fellow man. His mental sovereignty, his identity, and voice are all surrendered to the weight of the crown, rendering him burdened by a colonised mind.

Above: Jared Burton, King in a Snowstorm, Acrylic and image transfer on canvas, 2018

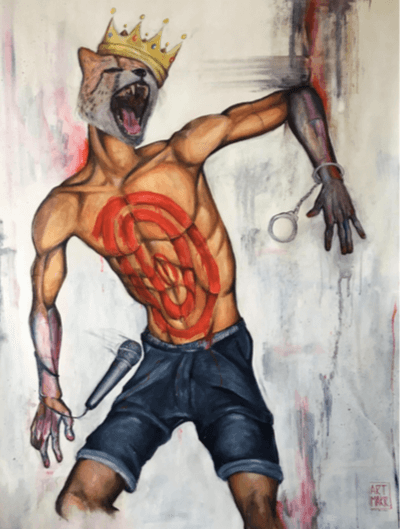

Moreover, following Burton’s King in a Snowstorm, we are met with a constricted cheetah- headed black figure. Tied between the tangle of a microphone and the lock of handcuffs, a red target denotes this crowned figure. These motifs are not symbolic in that the black body does not exist in the symbolic order within an

anti-black world.6 These motifs are just understood expectations, and social pressures weighed against the black body; they command blackness to either be entertaining or to be exiled, or not to be at all. Animal-faced, we cannot empathise with this figure as his humanity does not register in the social imaginary of viewers accustomed to a world of anti-blackness. King in a Snowstorm and Colourism in relation become a consequence of responding to the crown. A colonised mind may submit and engage in self-destructive puppeteered behaviour or it may resist and encounter the consequential oppressive force of an anti-black order.

Salvaging Black Masculinities

Within the black community, other emancipations provided grand opportunities for reconstruction, particularly concerning the perceptions of masculinity outside of warfare and power conflict over life and liberty. At the same time, they reduced the intensity of the struggle for political determination, economic power, and cultural self-definition. […] Implosive community violence remains an expression of subordinate black masculinities. The seemingly rudderless quest for an inversion of the dominant agenda has left the streets of communities, the language of social discourse, sexual relations, political dialogue and the lyrics of popular music shot through with violence, both virtual and real. […] New representations of subordinate black masculinities are taking shape in much the same way today that they were during the slavery period. Now, as then, these constructions are part of a process of subjectification necessary for the perpetuation of forms of discursive and discriminatory power.7

Above: Matthew Kupakwashe Murrell, Lil’ Boy (from De Angry Black Boy Tantrums) as performed at “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues,” 2018. Photo: Logan C. Thomas.

The theatrical productions of Matthew Kupakwashe Murrell perform experiences of black masculinities in Postcolonial Barbadian society. Delivering two performances as part of the exhibition’s programming, Murrell highlights both the social and historical sources and legacies pertinent to the shaping of the contemporary black Barbadian man. Performed consecutively, an excerpt from his De Angry Black Boy Tantrums, Lil’ Boy, and a new work, Unda My Fada Last Name, we are introduced to generations of black men failed by generations of varying social systems (from plantocracy to post-independence governance). Regarding the latter, Unda My Fada Last Name, ‘God Save the Queen’ begins playing alongside a projected montage of snippets of colonial legacy (such as English street names in Barbados and the Nelson statue in Heroes’ Square); introducing us to the colonial inheritance branded into both the land and its majority black populace. Following this presentation, the trio of black men stomps in unison, chanting a song denouncing their colonial fathers, givers of their last names, sources of their social predicament. The beat concludes with a final drum roll of stomping the ground, giving us an image of trauma and tantrum. It is not a tantrum to be patronised as it is laced with historical frustration and a begrudging resentment against a line of absentee fathers (between white paternal planters, colonial patriarchs, and negligent post-independence governments). Commanding their symbolic fathers to hold onto their last names, renouncing their inheritance, we are brought to read these last names, these ‘gifts,’ in the same light as hereditary disease. This work reads like a prologue to Lil’ Boy where we encounter the product of such colonial inheritance and the failed conditioning of black men in Barbados by a multitude of negligent paternal figures and guidance.

The introductory excerpt, Lil’ Boy, presents a trio of black men in Barbados, “[products] of your education system,” products and raw materials of the state, divulging on their being failed and damned. At one moment, fading into contemplation, there is questioning or search for paternal figures (uncle, father, etc.), foreshadowing Unda My Fada Last Name. Everything of this black man in the trinity is “state-owned,” including himself, putting his agency and humanity in question. Failings aside, there is a strong thirst for power, money, and respect which forces his hand towards violence. Violence becomes salvation in the neglected black male imaginary, and his faith begins to lie in the gun as these are the only gods that ever answered his prayers for social redemption and resuscitation, in the ongoing struggle for cultural, economic and political sovereignty and self-definition. This resilience in the striving for self-determinacy is necessary for the social climates perpetuating centuries and generations of negligence, abuse, subjugation and persecution of black men. Lil’ Boy repeatedly returns to the chant, “Grown but ain’t grown,” emphasising the fact that even though progress has been made in the social restoration and reparation of the black man, it is still not enough; there is always room to grow. He has come a long way or rather, the societies that possess him have progressed, but not far enough, as evidenced by his continued subjugation and still absent sovereignty and mobility. In relation, the two performances highlight this progress and the space left to advance. On his presentation within this particular site for the exhibition, Murrell’s works resonate with the unfinished brickwork of the River Road studio. In the heart of an intersection of streets named by their colonial inheritance, the studio – a space, incomplete and in development – reflects the reparation of black men in and out of Barbados, ‘grown but ain’t grown.’

Above: Ronald Williams, Shoe Game #1 (left), Shoe Game #2 (centre), Shoe Game #3 (right), Digital Collage on Archival Matte paper, 2018

Towards a celebration of black Barbadian masculinities, the Shoe Game series of Ronald Williams explores expressions and signifiers of class and status through fashion. Three figures pose from the legs down, embellished and decorated, in collage, with motifs of varying familiarity such as ‘timbs,’ cannabis-print joggers, money-print socks, a Louis Vuitton-print skull, Mount Gay XO rum trickling an overflow of dice, flying bullets and many more culturally loaded signs and materials. Individually, these materials are not particularly notable, but their collation and convergence in Williams’ images reflect on a culture of black masculine wealth and success as expressed through the achievement and donning of particular fashions and lifestyles. This personal and communal play with values of glamour through multitudes of ‘bling,’ should avoid being read as helpless assimilation into the consumptive throes of Capitalist society but rather, an act of joy through expressions of black decadence. Responding to a history of blackness shaped as a tool for labour and work, this personal consummation and flashing of borderline-kitsch cultural matter grants these figures passage to a state of jouissance that “breaks with any utilitarian concept of blackness.”8 That is, practices and celebrations of excess and decadence – the maintenance of lavish black lifestyles in the social pressure of ‘thrift’ weighed against the black working-class – allow joy in meaningless (meaningless as it relates to expectations of labour and social duty) expense and excess.9

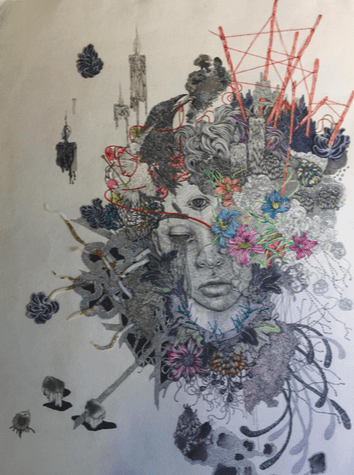

Above: Simone Asia, Dear Beloved, mixed media, 2017

A Disengaged Sovereignty

The body implies mortality, vulnerability, agency: the skin and the flesh expose us to the gaze of others, but also to touch, and to violence, and bodies put us at risk of becoming the agency and instrument of all these as well. Although we struggle for rights over our bodies, the very bodies for which we fight are not quite ever only our own.10

At this point, it is important to mention Simone Asia, whose work stands apart in its unique negotiation of a conflicted, contested Barbadian society. There is a potent sense of disinterest in Asia’s drawings, which allows room for self-contemplation outside the frame of determination, categorisation, and sociopolitical conjecture. Drawings overflowing with intricate organic patterns, textures, and forms, usually anchored to a solemn or resigned face, Asia’s work is a meditative exercise in release. There is a degree of mental and emotional investment in her work, demanding in its required patience and attention, making its production an act of reclusion or resignation. I do not say this in condemning tones but, instead, to address the effort of self-concern and self-determination involved in the making of these works. The faces as anchors to our own ordered and tangible reality, the alien organic forms seemingly consume this familiar order, or they radiate outwards from this facial focal point. Asia’s portraits somewhat escape and evade identity, prioritising the materiality of both orders; the familiar and the alien, line democratises matter, converging the face (the human) with the alternative values and forms of the organic, accommodating difference in a harmonious union. Two orders are living in one space; there is a therapeutic peace in viewing these drawings, a meeting point where conflict evaporates in a collision. Amid a very vocal and politically charged atmosphere instilled by the surrounding works, all driven in the search for self-definition and a reclamation or interrogation of self-image, Asia’s drawings stand with greater subtlety, becoming less concerned with a self-discovery determined by the categories, signifiers and hierarchies pertaining to our social reality and more concerned with an exploration of self through drives of inner contemplation and instinctual impulse. With this in mind, Asia’s self-image is disinterested from oppressive social orders that would seek to determine her image and condition and instead preoccupied with her conceptualisation and creation of an alternative material order, where her imagination holds sovereignty.

Our Clamour for Space

A community with a capacity to express and disseminate its culture through the arts, showcases its autonomy, independence, and self-affirmation, and therefore reflects some of the ideals and intentions of the Independence era. In Barbados, these attempts to rewrite and re-examine the history have suffered from a lack of support by the institutions whose mandate it was to encourage and support this development. And so the culture has reverted to the previously held cultural ideals linked to the ‘colonial model’ where validation and decisions come from ‘outside’ of the culture.11

In conversation with the momentary curator, Sheena Rose, her values, and experiences, as shaped by interactions and exposure to the global art world, have indeed provoked this curatorial experiment. Stepping back from her usual role as an artist, Rose feels it important to promote certain criteria in curation, selection, editing and display regarding the standards and conventions by which art is shown and seen in Barbados. Rose’s curatorial intentions involve a challenging of local criteria and priority in the arts. “People want to see themselves,” notes Rose in our conversation, as she discusses the need for promotion of art concerned with and emerging from the particular facets of Barbadian identity, made by Barbadians and for Barbadians. Against the inflated and highly prioritised tourist-marketed art scene, mostly concerned with images of the ideal, virgin paradises, souvenirs, tropical kitsch and the like, Rose hopes to level the playing field, wherein which there may be enough space and opportunity to accommodate definitions and functions of art beyond this particular market. Also pushing for expanded, more critical and selective ideas of curation, there is breathing room in the exhibition, compared to the salon-type style of display prominent in our few galleries and arts festivals, where everything is shown (including the kitchen sink). It is not a question of elitism, hierarchy or exclusion but more critical concern, with the hope of motivating a collective pressure to produce work of higher qualities and standards, through moderations of taste.

Excited about her space’s potential to be shared among her contemporaries, among her students, among her friends and others beyond her immediate circles, Rose’s intentions are, at their base value, to show what’s possible with the resource of space. Echoing past calls for a national gallery, Rose values space as every artist does. A resource so precious and sought after by the artist, in Barbados and elsewhere, space (for both work and show) is in short supply in Barbados, or so it seems. Though Barbados is riddled with disused and dormant spaces (abandoned factories, hotels, resorts, government buildings, to name a few), the past and present masters of our infrastructure, have yet to imagine any productive revision and use of these spaces (all annexed and inaccessible by the domain of sheer neglect). Returning home to Barbados in 2017, my ability to present work has been supported by parties of the local arts community (Sheena Rose, Punch Creative Arena, and Fresh Milk), with their own particular personal privileges and resources, all limited by a lack of institutional support. As artists, writers and curators, we cherish the potential that space offers us and its absence, our livelihood and our culture’s lifeblood. After all, if we must indeed “make bricks from straw,”12 then, at least, grant us the courtesy of a space in which to make and display them. All in all, “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues” is an experiment hoping to act as an example, demonstrating what is possible, whether lifted with support or burdened with neglect, when we pool our resources, talents, and efforts, together, as a community of artists in attendance and participation.

Above: Adam Patterson, Mangrove Village, as performed at “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues,” 2018

At this point, I must rescind my distance as simply viewer and return to my capacity as an artist who indeed performed in the space and context of “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues,” within that animated exhibition space planted in River Road. Without discussing the work and rather discussing my experience as a participant, “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues,” has indeed presented itself as an experiment and example, hoping to project itself and the values of a global contemporary art world forward into the mainstream Barbadian consciousness. Reflecting on my own work, Mangrove Village, performed on the opening night, seated for hours within a skin of Sargassum seaweed, the cheerful noise of visitors seeping through my veil, one line from my invoked recitation still rings clear – “Restless and starving for sovereign thought, our memory wrinkles a clamour to action.” Though I am not capable of offering a fair judgment of my performance, I can at least state my work’s intentions in hoping to offer a critique of our gradual cultural stagnation in Barbados. Refusal to act, refusal to change, refusal to grow – all these surrender us to a swamp of cultural stagnation, wherein which we forfeit our self-determinacy and agency to the mercy of others. Silent witness to every visitor’s presence on the opening night, the excitement of a culturally hungry audience clamoured through the space of “Contemporary Art / Contemporary Issues.” And just as that thirst was quenched, it may soon return if we, as a society, abandon our momentum. The passing of this exhibition must be met with the emergence of many others of the like, for we can no longer afford disinterest. Yes, I fear they’ll find our culture floating in the swamp. The world keeps moving, and so must we.

1) Martin Carter, “I Come from the Nigger Yard,” in Poems of Succession (London: New Beacon Books Ltd., 1977).

2) Suzanne Cesaire, “The Malaise of a Civilization,” in Negritude Women, ed. T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting and Georges Van Den Abbeele (USA: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

3) Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (NY: Grove Press, 1967), 116.

4) Lorraine Morales Cox, “Cultural Sampling and Social Critique: The Collage Aesthetic of Chris Ofili,” in Cutting Across Media: Appropriation Art, Interventionist Collage, and Copyright Law, ed. Kembrew McLeod & Rudolf Kuenzli (USA: Duke University Press, 2011), 208.

5 ) Edouard Glissant and J. Michael Dash, Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1989)

6) Lewis Gordon, “The Existential Dynamics of Theorising Black Invisibility,” in Existence in Black: An Anthology of Black Existential Philosophy, ed. Lewis Gordon (NY: Routledge, 1997), 69-79.

7 ) Hilary Beckles, “Black Masculinity in Caribbean Slavery,” in Interrogating Caribbean Masculinities: Theoretical and Empirical Analyses, ed. Rhoda E. Reddock (Jamaica: UWI Press, 2004), 225-243.

8) David Marriott, “On Decadence: Bling Bling,” E-Flux Journal, accessed February 02, 2018, http://www.e- flux.com/journal/79/94430/on-decadence-bling-bling/.

9) Ibid.

10) Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004).

11) Winston Kellman, “The Invisibility of the Visual Arts in the Barbadian Consciousness,” in Curating in the Caribbean, ed. David A. Bailey et al. (Berlin: The Green Box, 2012), 113-124.

12) Ronald Jones & Marlon Madden, “Stop Complaining and make bricks from straw, Jones tells BCC,” Barbados Today, accessed February 02, 2018, https://www.barbadostoday.bb/2017/11/05/stop-complaining-and-make- bricks-from-straw-jones-tells-bcc/.conc