by Jennifer Oladipo

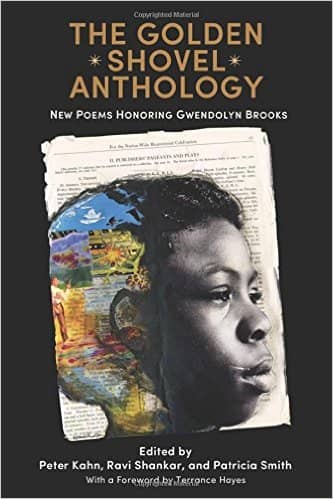

I recently sent a writer friend of mine brief email note. “Hi Peter. I’ve read everything I have. Got any suggestions?” Peter Kahn replied with an even simpler note, “Here’s the anthology I’ve been working on,” along with a link. There would have been no way for me to know the delight I’d find in what eventually arrived at my door, The Golden Shovel Anthology: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks. The book has the heft and variety of a college-level reader, which completely belies the playful new form it introduces to the world.

The book’s honoree, Gwendolyn Brooks, was the first black Pulitzer Prize-winning author for poetry. It’s content is several “golden shovel” poems, a form invented by poet Terrance Hayes, where the words from one line of a poem become the final words in the lines of a new poem. So, the writers in this anthology created new poems in which, if you read only the last words of each line, you’re actually reading a line of Brooks’ poetry.

Reading these poems has been an exploration, a journey, and a lot of fun.

Along with award-winning poets and co-editors Ravi Shankar and Patricia Smith, Kahn spent more years than expected working on this extensive book of poetry. Contributors included well-known writers such as Kwame Dawes and Camille T. Dungy, alongside scores of new writers, young people, and other writers who were new to poetry. Writers hail from places as diverse as the Caribbean and Europe.

Often referred to as the world’s first full-time spoken word teach at Chicago’s Oak Park High School, Kahn paused from a busy schedule of slam poetry coaching, teaching, traveling and book promotion to talk about the labor of love that became The Golden Shovel Anthology.

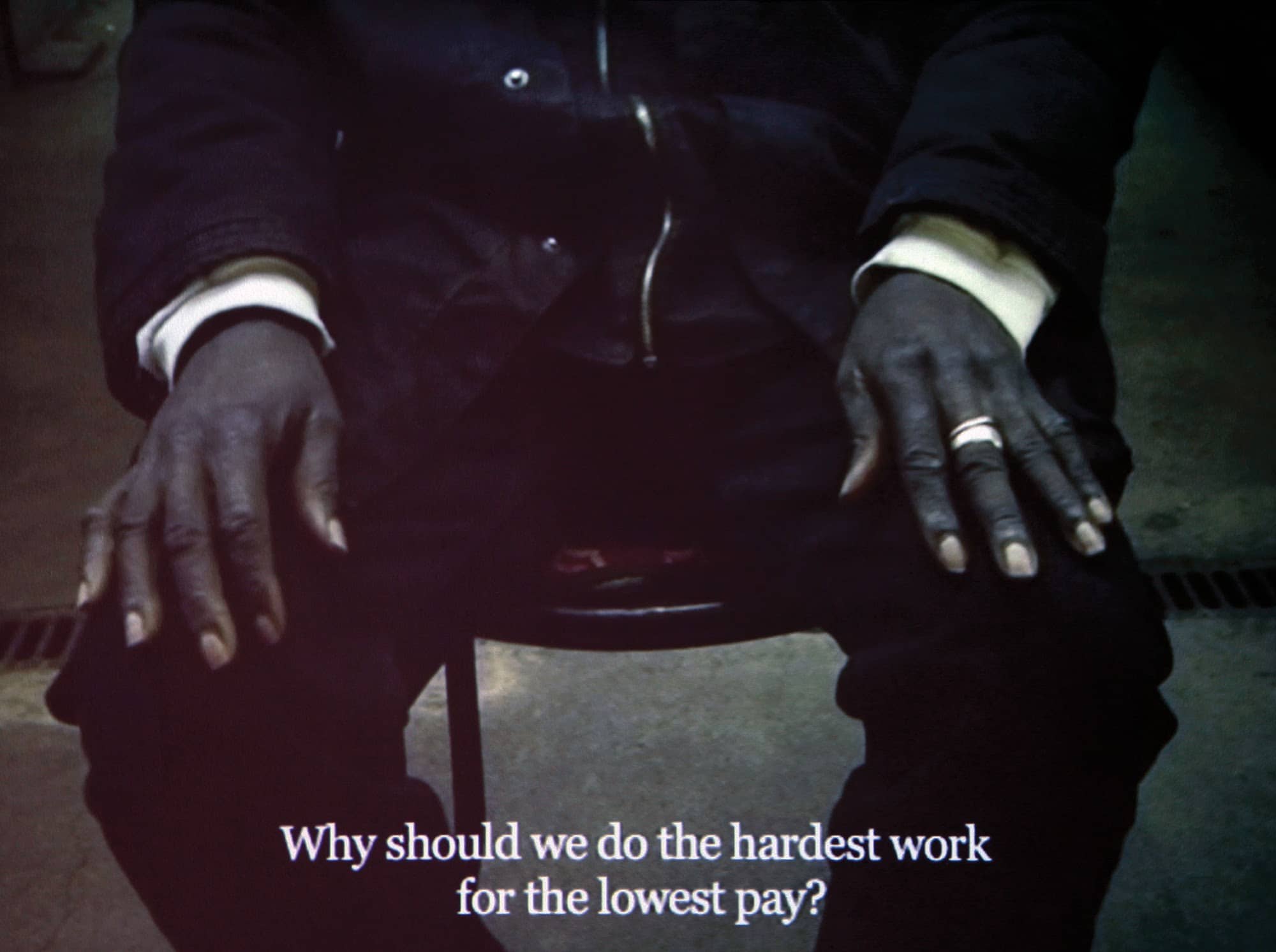

Jennifer Oladipo (JO): Why should people outside of the poetry community care about this work?

Peter Kahn (PK): One of the beautiful things about this form is your imagination takes over. Usually you have a poem and it’s just there. But this it’s an adventure you’re taking with Miss Brooks’ words, and you never know where you’re going to end up.

JO: How does the book help people engage with a new form of poetry?

PK: It’s a form that if you didn’t know you were reading a golden shovel poem, you’d just think you’re reading great poems. We have 10 poems by best-selling young adult authors.

We got permission to publish some of Gwendolyn Brooks’ poems in the book. An easy step would be to go to a golden shovel based on those. I think that makes it pretty unique that you can see the source for inspiration and the actual people, and see that conversation.

There’s also Terrence Hayes’ original golden shovel. He created a form and then he riffed off it in the second part of his poem. His intent was not to create a new form; he was just playing around with language.

Of course, anybody could just leaf through.

JO: Most of the time the new creations were very different, but there were some poems like Brook’s “The Bean Eaters” where all writers didn’t stray from the original themes. Why do you think that happened?

PK: It may be that “The Bean Eaters” is such a specific and odd poem that maybe the poem itself inspired people more than the line.

But then in Philadelphia launch, I read with the guy whose poem was right next to mine. Both poems derived from Brooks’ “Kitchenette Building,” which uses the word “gray” a lot. When you think of gray you think of aging, but mine and his are both very distinct poems. I think it’s fun as a reader to see two people take the same line in completely different directions.

Photo credit: Dominique Sindayiganza

JO: What’s been the reaction from young people in particular?

PK: [One recent] night we had this amazing reading where they still had to turn people away an hour and a half later. People were waiting with hopes they can get in. I had 10 of my former students there. The authors in the book might be somebody who they’ve read, like [children’s author] Sharon Draper, as well as their poetic heroes like Patricia Smith and Terrance Hayes. They’re smitten with it.

JO: What is particularly “Chicago” about Brooks’ poetry?

PK: I’m not a Brooks scholar, but my sense is that what she wrote explicitly or was implicitly set in Chicago. She wrote about things like Brownsville; Emmit Till, who was from Chicago; and the Beverly Hills area Chicago.

JO: What surprises did you find while working on this project?

PK: The biggest surprises are when I approached fiction writers, how they were willing to take this risk and go outside of their expertise. I think that speaks to the reputation of Gwendolyn Brooks: people wanted to honor her. The fiction writers and the student in most instances, if I took people’s names away from the poems, you would not be able to rank order people by experience or professional prestige. That’s not disparaging to the experienced writers, but a tribute to how less experienced writers rose to the occasion.

On the negative side, it took a hell of a lot longer than I expected. This year is year six. But that allowed me to reach out to writers I hadn’t heard of in that first year or two, people like Billy Collins, Rita Dove, Tracy K. Smith. But because it was spread out over about four years of me asking people, I could check back every six months to a year without feeling pushy.

Phillip Levine sent one, retracted it because he said it wasn’t good enough, then sent another. It’s beautiful. That was a pleasant surprise.

JO: What has this project taught you?

PK: It’s taught me most about a combination of inspiration and constriction. My mentors, when they talk about pushing you to try a form, it’s about restriction and being creative there. This book has taught me there is a sweet sport, a happy medium between free verse and form that now exists.

It also taught me how much writers want to be part of a community and want to pay homage. I didn’t’ pay anyone. Some of these people are commissioned to write poems. The sense of community that Brooks modeled, people leave these events inspired. Given the state of our country and this world right now, it’s easy to be depressed. But people are leaving these events smiling. They don’t want to leave. And that’s really inspiring.

JO: Is there anything else you’d like people to know?

PK: Just how it really is a great teaching tool for middle school to graduate school level. I wanted to make sure it’s taught in classrooms. Also, Gwendolyn Brooks definitely needs to be more in the forefront of the literary imagination and cannon.