As a marketer, I observe that Haiti’s brand identity is often framed between two narratives from “The First Black Republic” to “The Poorest Country in the Western Hemisphere.” (According to a recent Google search in 2025, Haiti was the first result for these terms.)

Having lived in Haiti for many years pre and post Baby Doc, witnessing and living through all the changes and turmoils the country experienced, I’ve yet to see Haiti the nation and the cultural brand defined with all the nuance it deserves.

Haiti’s unique position as a French- and Creole-speaking country meant that much of its art and literature has been translated and interpreted through external lenses, some more accurate than others. These external views often distorted or alienated the authentic voice of Haitians within Haiti, erasing local narratives and diminishing curiosity about how Haitians themselves define their nation.

This phenomenon is rooted in sociogeny, a concept explored by Sylvia Wynter in Towards the Sociogenic Principle: Fanon, The Puzzle of Conscious Experience, of “Identity” and What It’s Like to Be “Black.” Wynter critiques the translation of Frantz Fanon’s L’Expérience Vécue Du Noir (The Lived Experience of the Black) into The Fact of Blackness. She argues the latter suggests an objective, external perception of Blackness, whereas the former emphasizes the subjective, lived experience of being Black within a globally hegemonic, yet culturally specific framework.

To me, this framework also informs the perception of Haiti’s cultural and artistic identity, which is often translated and interpreted through foreign lenses. This brings me to Lionel Duvalsaint, one of my uncles, a Haiti-born art collector whose extensive collection of over 400 works spans from the 1940s to 2024.

Growing up, I was fortunate to be immersed in Haitian art through Duvalsaint’s collection. Studying Gérald Alexis’ Peintres Haïtiens from cover to cover, I was able to see the works of most of these artists firsthand. Over the years, Duvalsaint and I have shared many conversations about the ways Haitian art is predominantly presented to the world—often filtered through themes of Vodou and folk art, with artists like Hector Hyppolite frequently serving as the focal point, particularly for his ties to surrealism.

In a series of exchanges, Duvalsaint shared the beginnings of his journey as an art collector and why it was so important for him to focus on Haitian art. The goal of this exchange was to provide more context to Haitian art from the lens of a collector as a way to convey not only the accessibility of art but also its potential to inspire and ground one’s cultural identity and individuality.

Lionel Duvalsaint was born in June 1951 in Port-au-Prince and raised in the region of L’Artibonite, Haiti. The son of a mill owner and a seamstress who owned her own atelier and taught sewing, Duvalsaint today is a civil engineer with a company that specializes in irrigation and sanitation, with projects in Haiti. He was educated in Haiti, Canada and the United States.

Samia Grand Pierre (SGP): What was the first piece of art you purchased?What attracted you to it, and where did you find it?

Lionel Duvalsaint (LD): The first piece of art I purchased was a Last Supper (20×30 inches) carved in wood, circa 1973. At the time, I was a university student, and as a Christian, I was captivated by the reproduction of such a significant religious scene. In Haiti, it was common for artists to walk through neighborhoods with their creations, offering their work to residents on their porches. I negotiated with the artist who happened to pass by my house on Rue Vaillant in Port-au-Prince. That piece marked the beginning of my journey as a collector. I still cherish it to this day.

SGP: Do you remember what your second and third pieces were after that first purchase?

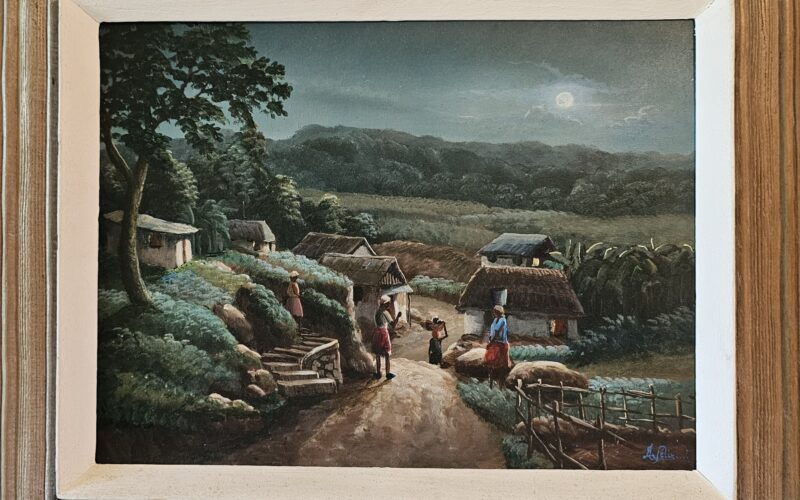

LD: The other two pieces of art I acquired were by Jean-Félix Defournoy (1952–), created around 1980. Defournoy won first prize in a contest organized by the French Institute in Haiti (Connaître les Jeunes Peintres), earning him a scholarship to study in France. He began painting in 1971 and is still alive today.

SGP: What motivated you to continue buying after acquiring a few pieces? Does any one in your family share your passion for art collecting?

LD: When I was a student at the Faculty of Sciences, the dean, Feu Maurice Latortue, an art collector, used to invite us, future architects and engineers, to visit his collection. My passion for art started from there. He used to talk to us about Haitian art, its importance in the Caribbean.

He also advised us to collect art like Haitian art, which mostly tends to be bought by foreigners, and as a result of this, future generations will not have access to the wonders produced by their own people. Those words have had a lasting effect on me.

There was no one in my family from the previous generation who was a role model, encouraging me to collect art. And I am the only one in my generation of the family to have developed such a passion. However, I can say that one of my brothers has developed a very moderate passion for collecting Haitian art.

SGP: Does the potential future value of a piece influence your acquisition of an artpiece?

LD: My attitude towards art, specifically Haitian art, is not motivated by its future value. I want to make sure to preserve the rich cultural legacy of Haiti for Haitians and be useful to expand on how this art is viewed, documented and understood in the rest of the world. After more than 50 years collecting art (1973-2024), I have never sold a piece. I have, however, found people interested who offered me money for some pieces of my collection.

SGP: What are some Haitian artists currently part of your collection?

LD: Hector Hyppolite, Georges Remponeau, Pétion Savain, Luckner Lazard, Bernard Séjourné, Gérard Valcin, Fravrange Valcin (Valcin II), Enguerrand Gourgue, Frankétienne, Sénatus Louis, Luce Turnier, Rose-Marie Desruisseau and Émilcar Similien, known as Simil to name a few.

SGP: You have an extensive amount of ValcinII’s work. What compelled you to own so many of his works?

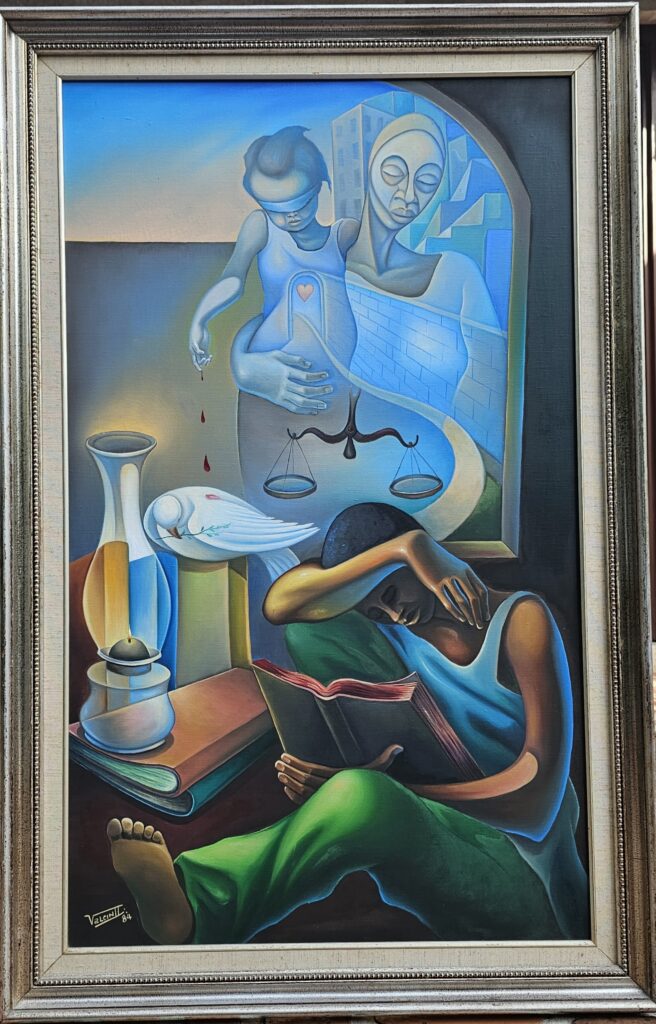

LD: Yes, I own over 30 paintings by Valcin II (Fravrange Valcin) in my collection. In December 2010, one year after his passing, I held an exhibition showcasing these works.

My favorite piece is Le Doralys, which I commissioned from him in 1984. This painting portrays the theme of family separation, a deeply personal subject I was grappling with at the time. When I shared my story with Valcin, he immediately connected, as he was going through a similar experience. Over three months, he poured his emotions into creating a piece that was both heartfelt and relatable.

I was introduced to Valcin II by a gallerist after expressing my desire to collaborate with an artist who could address such a subject. I was deeply impressed by his ability to translate such a personal subject into a painting. I was really pleased with Le Doralys. From that point on, I adopted him as my favorite artist, acquiring one or two of his paintings each year.

Over time, we became friends, and Valcin introduced me to an influential circle of Haitian artists, including Jacques-Enguerrand Gourgue, Gérard Valcin, Carlo Jean-Jacques, Pierre-Joseph Valcin, Franck Louissaint, Jean-Louis Sénatus and many others. These connections allowed me to acquire artworks directly from artists I consider to be great masters while also deepening my knowledge of Haitian art.

Valcin was known as an activist artist, unafraid to address social issues during Haiti’s dictatorship in the 1980s. This set him apart from the proponents of what was then called “the School of Beauty,” led by Émilcar Similien, Bernard Séjourné and Jean-René Jérôme, where adherents presented art as pure beauty in mostly soothing colors and subjects, avoiding anything jarring.

SGP: Your collection also features Bernard Séjourné. Why is he significant to your collection?

LD: I didn’t know Bernard Séjourné, personally; he was from an upper-class family in Haiti. I had access to his works only after his passing in 1994. I own over a dozen pieces of his art. My favorite one comes from his private collection and is called L’Acheron, known in Greek mythology as “The River of Woe.” In the painting, he depicts the crossing of the river. In mythology, the river is one of the five rivers of the underworld and is often depicted as a boundary that the souls of the dead must cross.

I believe that owning his work is vital in the representation of Haitian art. Bernard Séjourné also had an international reputation; he was commissioned by Baron Philippe de Rothschild to create the label for the 1986 vintage of Château Mouton Rothschild. The label design featured a trio of masks emerging from darkness in his unique aesthetic.

As a note, Salvador Dalí was also part of this prestigious tradition, designing the label for the 1958 vintage of Château Mouton Rothschild.

SGP: Which piece of Luce Turnier is your favorite, and what led you to include her work in your collection?

LD: Luce Turnier was celebrated as the Grande Dame of Haitian painting, and for me, it also was important to own her work. From my collection, my most cherished piece is The Sleeping Lady, the final painting she created. The subject of this work is a woman who had posed for Turnier since her adolescence. It depicts a seated nude, which I interpret as a metaphor for Haiti, our country exhausted from exploitation by outsiders.

SGP: You also own some work by Frankétienne. Why is his work meaningful to you?

LD: Frankétienne is a real giant when it comes to literature, science and art in general. My favorite piece of his is an abstract dated 1983, part of his works considered to be from the best period of his production. He was an “activist artist” fighting with his literature, theater representations and paintings against the dictatorship of the Duvalier regime. I was particularly attracted by this kind of intellectuality or cerebral form of expression in art.

SGP: What do you think I sa common misconception about art collecting?

LD: Collecting art solely as an investment is a common misconception. From this perspective, there is no real connection between the piece and its owner. It becomes a superficial process of “buying, packing, and waiting for the best value.” The owner often neglects to appreciate the beauty of the artwork or take the time to understand the message it conveys.

Personally, I do not view art collecting through a business lens. In fact, despite being solicited, I have never sold any piece from my collection.

SGP: In the representation of Haitian art, why do you think folk art is so often emphasized? Do you believe other forms of Haitian art deserve greater recognition?

LD: When, in 1944, American watercolorist Dewitt Peters founded the Centre d’Art in collaboration with Haitian artists such as Maurice Borno, Albert Mangonès, and Gérald Bloncourt, his focus leaned heavily on what he referred to as “naïve” or “primitive” art. In a 1947 article in Harper’s Bazaar, Peters described this as “real art,” produced by individuals with little to no formal training who nevertheless managed to organize the space on a canvas in compelling ways.

Exhibitions of these works in Haiti and abroad soon attracted international collectors from the United States, France and museums, who were captivated by the originality of this “folk art” and the connection many artists made to Vodou, which reinforced this notion of a magical Haiti. Many of these pieces, initially purchased for just a few dollars, were later taken abroad and preserved.

Le Doralys

In contrast, few Haitians purchased these works at the time, often dismissing them as overly simplistic or “childish.” By 1950, tensions arose within the Centre d’Art, leading to its fragmentation. The more advanced artists, referred to as “Les Sophistiqués”(“The Sophisticated”), broke away to establish their own space, the Foyer des arts plastiques. This movement was spearheaded by artists such as Max Pinchinat, Dieudonné Cédor, and René Exumé.

The emphasis on early folk art, which is now scarce and primarily in the hands of foreign collectors, perpetuated the idea of Haiti as a nation of naïve artists, anchored on Vodou, unable to access more modern or sophisticated forms of expression. However, this narrative overlooks the fact that other artistic traditions in Haiti existed long before Peters’ arrival.

For example, my collection includes works by significant artists such as Pétion Savain (1906–1973), Georges Remponeau (1916–2012), and Andrée Naudé (1903–2003). These artists exemplify the broader spectrum of Haitian art, which spans from pure naïve art to contemporary styles.

Haitian art encompasses a rich tapestry of expression, reflecting the depth and complexity of the nation’s artistic heritage. My hope is that this conversation helps bring greater attention to all forms of Haitian art, and inspires collectors and enthusiasts to continue discovering and acquiring work driven by passion and admiration.