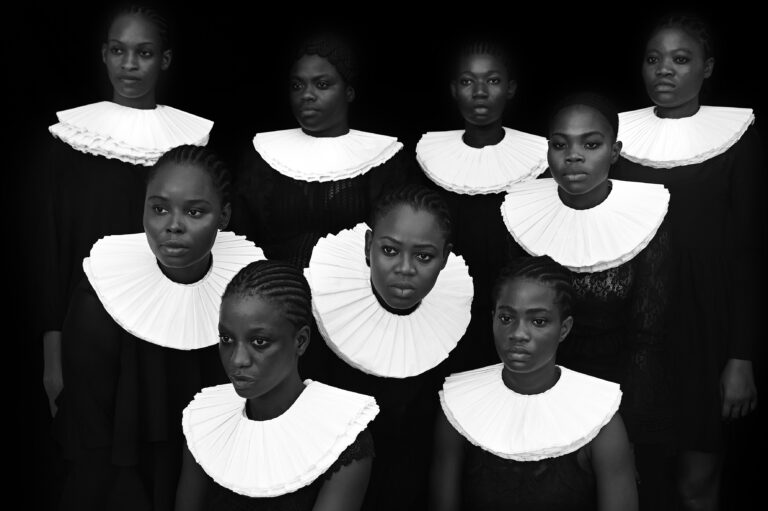

Above: Sonya Clark (pgs. 346-351) Photographer: Alaric S. Campbell. Excerpted from Crafted Kinship by Malene Barnett (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2024.

Brooklyn, N.Y.-based, multidisciplinary artist and surface textile designer Malene Djenaba Barnett prides herself on being a community builder for a global network of Caribbean artists working in craft traditions. Splitting her time between a robust art practice and an unwavering dedication to community, she considers the work of building connections between artists to be foundational to her art practice.

By supporting those she calls makers—artists with rigorous practices that defy rigid definitions of craft, design and fine art, she inspires a collective dismantling of the hierarchical privileging of singular approaches to fine arts. For Barnett, building pathways for makers to collaborate, share their experiences, and elevate each other’s work is paramount to uniting African diaspora communities despite their geographic divides.

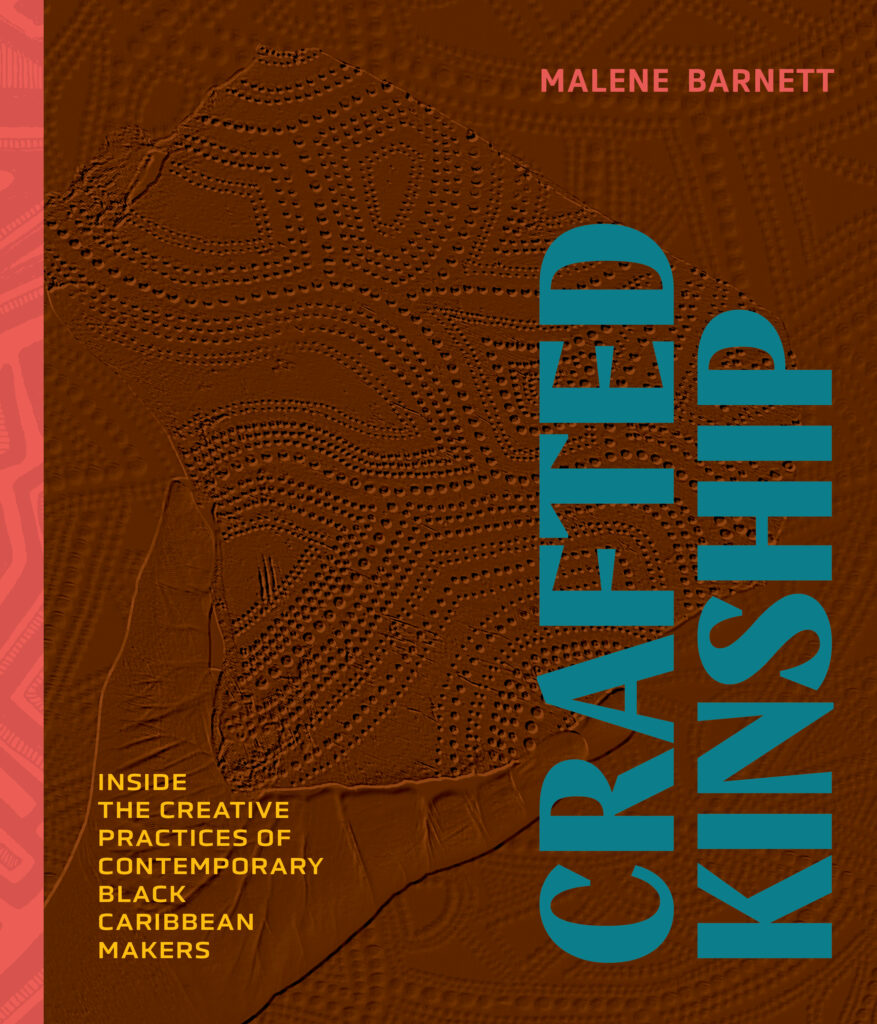

Her latest book, Crafted Kinship: Inside the Creative Practices of Contemporary Black Caribbean Makers, features interviews with over 60 artists, including Andrea Chung, Fabiola Jean-Louis, Lisandro Suriel, Mark Fleuridor, Nguyen Smith, Renee Cox and Sonya Clark. The book also reveres the lives and creative careers of ancestors Althea McNish (Trinidad and Tobago, 1924-2020), an esteemed Britain-based textile designer, and Ronald Moody (Jamaica, 1900-1984), a master sculptor. Crafted Kinship is a beautiful archive of intimate conversations with world-renowned and emerging makers about their practices, processes and inspirations. The project is guided by Barnett’s queries about the intersections of history and identity in her own creative practice and, by extension, that of other Caribbean makers.

“How does having a mother from St. Vincent and a father from Jamaica—the first and last Caribbean islands to be colonized—inform my sense of identity and multidisciplinary creative practice?” Barnett ponders in the book’s introduction. “How does my identity as a member of the diaspora inform my work, and how does it intersect with the work of Caribbean makers who were raised in the region, including those who have remained in or returned to their Caribbean lands?”

Crafted Kinship is a testament to the reality that despite the Caribbean’s relatively small population, the region’s historic global impact cannot be denied. Many of us have been taught to consider art, design and craft to be innately unrelated practices. Barnett works to demonstrate the ways contemporary Caribbean makers and their predecessors are constantly activating nuanced, interdependent and multidisciplinary interventions that intentionally defy categorization.

“The beauty is that there is not just one answer, right?” Barnett shared with me during a recent interview. “That is also what I’m trying to get at, the multiplicity of ways of being, ways to explore Blackness, and how we are all coming from different perspectives. What brings us together as a community is that we are making: making space, objects, clothing—we’re all making. And that’s the part that I really want to emphasize.”

Barnett argues that each maker’s distinct interdisciplinary approach is still interconnected, across space and time, by cultural and spiritual ways of being that survived the Transatlantic Slave Trade and continue to be elucidated through art, design and craft. Barnett’s conversations in Crafted Kinship highlight all the subtle threads that connect global Black communities and make our experiences unique. It is surprising, then, that Crafted Kinship remains one of the few books grappling with these subjects while also affirming a new generation of Caribbean makers.

“Being in Western society, we are forced to pick a discipline or medium and hone it,” Barnett continued. “If I think about this from an African-centered perspective, we made it because we needed these objects, or needed space, or clothes, or wanted to celebrate. These objects all had a purpose. There is no division between high-art and low-art craft. It’s really important for me to stay with these materials and elevate them in ways that bring awareness that there is no hierarchy between materials.”

Barnett has been a steward of supportive networks for Black creative professionals for many years. In 2018, she founded the Black Artists + Designers Guild as a member-driven platform to empower collaboration and to help Black creatives find community. She considers this work divinely guided, informed by ancestral perseverance and the demanding realities of global Black experiences. At all times, revealing how history and culture always inform art is critical to Barnett’s practice.

“The more we collaborate, the more we can thrive and grow as a community,” she said. “Nobody is successful by themselves. Especially as Black people in spaces where we’re not always welcome, we are empowered to know that we can show up unapologetically. My work is very collaborative, and it’s in conversation with my ancestors. Still, it’s also in conversation with the present, with the community at large, trying to engage them to think about the African American experience through a Caribbean diaspora lens and expand what the African American experience is. It is central to this land and many liberation freedom fighters, many of whom have Caribbean roots. There is a synergy between the spaces. I want to build community in that way.”

The artist learned to work with textiles from her mother and through stories about her maternal grandmother, a fashion designer. The meticulous way they worked with materials, turning jute into macrame wall hangings and sewing beautiful clothes, inspired Barnett to gravitate towards textile, design and craft.

She dedicates Crafted Kinship to the matriarchs in her bloodline and in honor of all the warriors who enable Black futures by reimagining Black archives. Barnett’s intergenerational and multidisciplinary selection of artists celebrates and affirms that Caribbean makers have contributed continually to the evolution and innovation of art, craft and design industries worldwide.

“If you look at a fabric, the cotton was picked, the yarn was hand-spun, and it was handwoven, intricately sewn together, and then somebody is wearing it to celebrate life,” Barnett affirmed. “There is no question that this is not a beautiful way of being, right? This object, this is art.”