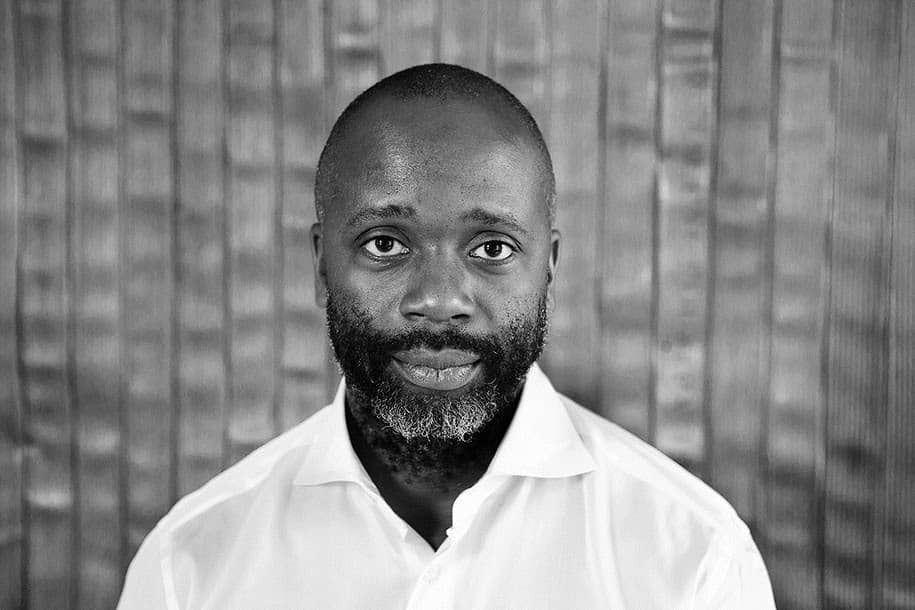

Above: This Titus Kapar work was chosen because of a quote by Dr. Erica Moiah James “I saw several instances of artwork that made me uncomfortable,” Dr. Erica Moiah James, art historian, curator and assistant professor at the University of Miami shared via correspondence with this writer. “A little Titus Kaphar here; a sprinkle of Kehinde there.” Titus Kaphar (American, born 1976). The Jerome Project (My Loss), 2014. Oil, gold leaf, and tar on wood panel, a, in travel frame: 214 lb. (97.07kg). Brooklyn Museum, William K. Jacobs, Jr. Fund, 2015.7a-b. © artist or artist’s estate (Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

In art, appropriation involves borrowing or copying images, music or other mediums and altering them. Appropriation is not a new trend. It prominently appeared in the intentional replication imbued in pop art and innumerable other art movements. In the 1900s, modernists copied aesthetics that were clearly derived from African, Indigenous, Asian and Polynesian artisans. Adaptation, riff and remix have long been compelling elements of Black aesthetics and cultural innovation. Black musical traditions have influenced the improvisational mark making of abstract expressionists.

The laws that address appropriation are nebulous and complex. Appropriation might have advanced the canon of many art movements, but copyright laws cannot disallow an artist from copyrighting a style or aesthetic, no matter how notable the artist makes that style. Our ability to use what we have, to make new meaning through experimentation and expansive imagination, becomes a complicated inheritance of post-colonial Black life. Demarcations between reference, appropriation and plagiarism remain blurred, and answers to questions about protecting artists’ creative rights remain in flux.

The monetization of Black aesthetics often is coupled with presumptions of scarcity. A systemic notion that only a few talented Black artists, American or elsewhere in the diaspora, can become successful in their lifetime prevails. Increasing competition in art markets to procure Black art, with a particular interest in representational art, even if those representational styles are reflective of another artist’s predominant aesthetic, compounds the issue. Understandings about appropriation and the merit of authenticity are debated in bullish blue-chip art markets.

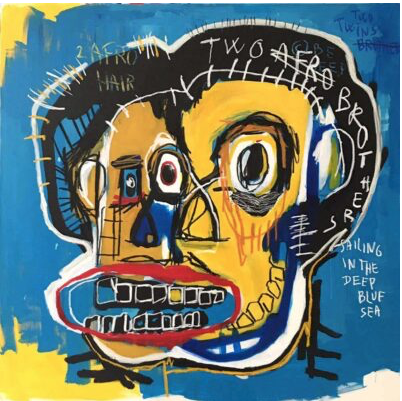

How do our thoughts about appropriation and accountability shift in instances where white artists incorporate Black aesthetics in their art? In 2019, French painter Guillaume Vera was accused of blatantly plagiarizing the work of renowned artist Jean Michel Basquiat. After significant pressure from the art community, Galerie Sahura cancelled a solo exhibition of Vera’s work.

Above: Guillaume Verda, 2 Brothers.

Despite the cancellation, the director of the institution, Jean-Baptiste Simon continued to defend Vera, arguing that a homage to a well-known artist was not plagiarism. If not for the viral outcry from photographer-filmmaker Alex Loembe, who posted a series on Instagram calling out Vera for his lack of citation but clear reference to Basquiat’s style, the exhibition likely would have continued, and Vera and Galerie Sahura would have profited from the sale of works that closely resembled those created by Basquiat.

In many instances, referential materiality may be the foundational component of an African or diaspora artist’s completed work. How does institutional hesitance to navigate creative rights for Black artists complicate the ways we appraise and validate Black aesthetics, as products or as processes?

In 1996, Harvard University threatened legal action against interdisciplinary artist Carrie Mae Weems, claiming that she appropriated incredibly rare Zealy daguerreotypes from their collection in her notable series, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995-96). The daguerreotypes depicted some of the first known photographic images of enslaved Africans in America. Weems incorporated some of the subjects in her series and overlaid them with humanizing texts that revealed the viciousness of chattel slavery in America. Although Harvard never followed through with its threat, the case set a significant precedent.

In an ironic turn of events, Tamera Lanier, a descendant of the Africans depicted in the daguerreotypes, sued Harvard University in 2019 for ownership of those images and compensation for monies earned from the use of those images. In March 2021, A Massachusetts state court dismissed the case. The film, Free Renty tells her story.

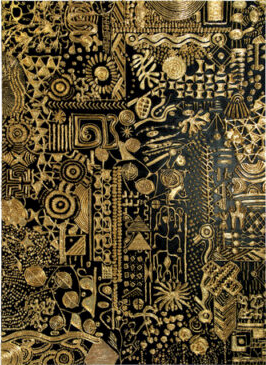

What complications arise when Black artists reference works by other Black artists, but do not compensate or cite the original artist in their revised work? In 2018, British Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor filed a claim against rapper Kendrick Lamar, claiming that references to her painting series, Constellation (2017) appeared without her consent in the music video, All Stars, a single featuring Lamar and SZA for the Marvel Black Panther soundtrack.

Above: Lina Iris Viktor, Constellations IX, Pure 24K Gold, Acrylic, Varnish on Matte Canvas. 60 x 84 in. / 152.4 x 213.4 cm

Viktor’s major claim was that the aesthetic motifs featured in the video—geometric gold leaf designs set against jet black backgrounds, were sourced from her original style. Victor sued Lamar for a portion of the profits gained from sale of the single and the soundtrack, but also noted that it was the principle rather than compensation that she was most concerned about. Later that year, the case was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum in favor of Viktor.

“It’s a nuanced conversation where I don’t think we are going to be able to come out with a binary solution,” visual artist April Bey noted in an interview with this writer. “Let’s just talk about etiquette in the art world—integrity and if you are going to make work that visually looks like someone else’s, and it’s not a commentary on their work, then maybe you need to push yourself. Try some more materials or have some happy accidents and actually work through your process instead of trying to get the aesthetic as close to what we think is selling.”

After nearly two years of COVID-19 pandemic-related shutdowns and virtual exhibitions, major fairs, including Frieze and Art Basel Miami reopened for hybrid in-person and virtual exhibitions. Though popular venues, including Untitled, showed an increased sensitivity to inclusivity, exhibiting several Black-owned galleries, there was also a notable uptick in the display of artworks by lesser-known artists whose styles were almost identical to prominent African American artists.

“I saw several instances of artwork that made me uncomfortable,” Dr. Erica Moiah James, art historian, curator and assistant professor at the University of Miami shared via correspondence with this writer. “A little Titus Kaphar here; a sprinkle of Kehinde there. The Deborah Roberts shadow play was perhaps the most disturbing and disturbingly obvious. There was absolutely no effort to transform. The boldness of the maker and the gallery to share that work in that space was stunning.”

Above: Lynthia Edwards, Flower Girls, 2021, Acrylic cloth, fiber and collage on canvas. 72 × 60 × 2 in, 182.9 × 152.4 × 5.1 cm.

Historically, mixed media artist Lynthia Edwards has engaged painting and quilt work to create portraits that illustrate Black Southern girlhood. In 2019, Edwards began to exhibit more traditional collage works that allegedly resemble, and in some instances, allegedly mine the same source material as established award-winning artist Deborah Roberts. Edwards, who is represented by the Richard Beavers Gallery, did not respond to requests for comment about her recent use of collage. In response to this writer, Deborah Roberts issued the following statement:

“In no way shape or form would I ever prevent any artist, especially artists of color, from making a living, because this is a very tough profession. My track record with helping young artists develop their skills and their own voice is easily researchable. What I object to is someone creating work knowing that it is being mistaken as mine and using that for profit. This is not about competition; it’s about having integrity.”

Collage is a medium that relies on the surgical extraction of fragments from photographs, usually archival images, magazines or newspapers, and sometimes original photographs taken by the artist, to create new images, figures or landscapes. Modernist artist Romare Bearden elevated this technique by bringing the humanity of African American communities in Harlem into focus.

In 1963, Bearden formed the Spiral Group with a cadre of esteemed artists to create a space for the discussion of art and civil rights. After pondering the possibility of contributing to a collective work in a dynamic way, Bearden began to experiment with collage by cutting out images from his wife’s collection of women’s magazines. To avoid the appropriation controversy entirely, Bearden transformed this technique. In a 1979 interview with Inside New York’s Art World, Bearden described his adapted collage process:

“Collage was an ideal medium for me, because at that time, I was interested in doing something that would say, ‘you are there,’ and there is so much conditioning now from the television, and the size of the television screen and the immediacy of it, and also, as Paul Valerie says, ‘man’s patience has been killed by the machine.’ And so, if you put all of the great artists together, you couldn’t paint something anymore with the realism of van Dyck, and Durer and these artists. Even the magic realists, you know it comes from the photograph. But you have to have the patience to sit down and do this.

“So, I could cut out the pictures and make the collage from that, and that was how I first did it. And then, I said, ‘you know look, I’m cutting out pictures, like these two ladies sitting here in the front, and they might sue me for doing this,’ and then I had to think of other ways of doing it so that it wouldn’t be actual people. So now, a lot of people say, well you must have a great morgue of photographs and things. No, I don’t. All of the things that I do, I cut out, I just make up. Really, the way I do my collage now is like drawing or painting. That is how it has evolved at the present time. There is no face that you see that is actual, they are all cut out and put together like a mosaic.”

What is most telling about this statement is that Bearden not only acknowledged the catch-22 of the medium of collage, but he also adjusted his approach to maintain the integrity and legality of his practice. However, when an artist considers their work to be a reference rather than an appropriation and does not fear legal action, there are few deterrents to prohibit them from monetizing the resulting work. Will it ever be possible to add more protections at the galleries, fairs or auctions to mitigate the acceptance and sale of appropriated or minimally altered works?

Dr. James said, “This isn’t just on the artist. It’s the entire system. We like to think of art in kumbaya ways, and that is there, but at this level, it is also an expensive commodity. The market demand for the work of Black artists in general is intense, and the market needs to be supplied. Ethics often take a back seat.”

The desire to make work that sells is a significant contributor to the rise in this phenomenon, and without accountability from art institutions, or a collective agreement about what moving with integrity entails, it will be difficult to shift artists, collectors and galleries away from this conundrum.