Legend has it that the Statue of Liberty was supposed to be a sister. I like to imagine that sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi would have chuckled at the brutal irony of his commission. The forced, free labor of kidnapped Africans instituted capitalism and established America and Europe as world powers.

For the United States of America, a country founded on the genocide of First Nations and the subjugation of Africans to task Bartholdi with fashioning a monument to proclaim its status as a distinguished and principled democracy is deeply disturbing and fascinating. To the so-called founding fathers, the African, the negroid, the Negro, the nigger, was barely 3/5 human. One cannot help but wonder what a Black revisioning of Liberty might have facilitated.

Insidious as smallpox, undeniably supremacist proofs resound in the likenesses that have been erected as monuments across America. Monuments are origin myths. Their passive presence proliferates a propaganda of colonial empire. How has their subsistence prohibited possibilities for progress?

Empire building is never civil.

History is never neutral.

In the seminal text, Black Reconstruction in America 1860-1880, scholar and anthropologist WEB DuBois recalled bearing witness to rampant ahistorical scholarship about the Reconstruction, the era that followed the Civil War: “…it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth.” The violence of that inaccuracy is reified by the creation and installation of Confederate monuments.

Why would a nation dedicate monuments to mutineers? Why has the South’s defeat been celebrated as a victory?

“In order to paint the South as a martyr to inescapable fate, to make the North the magnanimous emancipator, and to ridicule the Negro as an impossible joke in the whole development,” DuBois wrote.

He went on to articulate. “The South was ashamed because it fought to perpetuate human slavery. The North was ashamed because it had to call in the Black men to save the Union, abolish slavery and establish democracy.”

If you are not white or male or heterosexual, it is likely that the narratives that comprise your history have been confined to the margins of predominant pedagogies. You will be called a minority, and because the predominant culture views you and your histories as minor, they will be optional to engage. The elective curricula will incite rather than pacify your desire to see more of yourself reflected in the overwhelmingly white doctrines that comprise your education, and you will rebel against or be subdued by indoctrinations that submit written texts, white supremacy and colonization as evidence of civilization. You will be disappointed, but not surprised to find your history decentered and decontextualized by the limits of marginalization.

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass held strong beliefs about the individual responsibility and accountability that nations must uphold to ensure progress. “The choice which life presents, is ever more, between growth and decay, perfection and deterioration. There is no standing still, nor can be. Advance or recede, occupy or give place—are the stern imperative alternatives self-existing and self-enforcing law of life, from the cradle to the grave.”

Progress requires us to dismantle the decayed and fragile relics of an unresolved and yet eradicated supremacy. Balm on a gangrene limb will always be ineffective. Sometimes the only answer is amputation.

“Are destruction and hope my only models?” Hilton Als queried in an editorial about the possibilities of progress and the burden of forgiveness that post-civil rights generations must consider. The apathy of our nation sanctions recurrent violence against Black and Latinx lives: it enables maniacs to weaponize their fear into murderous acts and soothes the tantrums of Karens when they weaponize their privilege into murderous intent. For them, noncompliance and Black death are always synonymous.

The pathology of supremacy that enables white bodies to regulate nonwhite bodies is reified by Confederate monuments; each statue is a spiteful gesture; a psychic and corporeal indoctrination that normalizes, reinforces and historicizes the dogma of racial superiority as an unfortunate but collectively accepted trademark of American culture.

In the wake of global uprisings calling for accountability, reformation and the dismantling of old inequitable systems, artists are engaging the limits of history and imagining futures that decenter and problematize provocateurs of racialized violence. If you accurately contextualize the monuments of Columbus, Tawny, Lee, and Sims, they can be historicized not as heroes; but as tyrannical impediments to the nation’s realization of liberty and justice for all. The nomenclature “for all” must include First Nations, LatinX, LGBTQIA+, Black and Othered lives.

Through the creation of critical community-centered interventions, site-specific installations, and innovative, sculptural objects, emerging and midcareer artists are redefining the form and function of monuments.

In Where monuments go to die? a forthcoming project and For Whose Sins? (2011), interdisciplinary artist, educator and cultural strategist Omolara Williams McCallister asks us all to imagine a world where monuments die.

For Whose Sins examines the tenuous relationship between what McCallister calls “morality and sin, desire and disdain, as it relates to anti-Black racism in the U.S. South, Black male bodies, white masculinity and white supremacy.” The soft, sculptural work is comprised of 3,440 nooses, one for every recorded instance of Black lynching between 1888 and 1968. The compounded nooses form a drooping cross; each knot is bisected with a long iron nail. The hanging work is a triggering reminder about the historical prevalence and contemporary recurrence of violence against Black bodies. In the spirit of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, in Montgomery, Ala., For Whose Sins stood as a monument for martyred Black lives.

“As artists, we have a unique opportunity to be architects of society in that we are uniquely positioned to infiltrate both public and private spaces.” McCallister continues. “A single succinct image or icon, be it a noose or a clever icon, has the kind of immediacy and accessibility that allows it to stay with us… to catch our attention and embed itself in our subconscious.”

Indoctrination occurs at a corporeal and psychic level. Art and large-scale sculptural objects are profound tools for the recalibration of our collective imaginations.

“American culture has nurtured false images of People of Color and condemned Blackness without understanding who we are.” Multidisciplinary artist and educator Oletha DeVane, shared.

“In these times, as artists, we have to reframe the story, claim our spiritual and social heritage and retell it with absolute conviction. Not every piece of work is going to do that and not every artist has social change as a goal, but for now, we should seek to manifest truth in as many voices as possible.”

In 2019, DeVane exhibited Traces of Spirit, a site-specific installation comprised of multiple sculptural objects from inside a spring house that was sourced from a plantation owned by Senator Robert Goodloe Harper and Catherine Carroll. The spring house was later designated a historical home, and relocated to the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The central work, Saint for My City, a large sculpture composed of beads, plaster, glass and wood, 14 feet high, revisions the Madonna as an onyx black icon, and is surrounded by four smaller “spiritual sculptures,” Woman Who Married a Snake (2017), Spring (2018), Two Daughters (2007), and Health (Pilgrimage) (2018), statuesque assemblages constructed with iconography inspired by African traditional religions. DeVane’s work speaks to the monumental persistence of Black faith traditions as resolute catalysts for liberation.

“Monuments are not just statues; they are symbols,” conceptual artist and self-described cultural vigilante Tasha Dougé noted. “My work challenges national iconography and text [including] the American flag and the Pledge of Allegiance.”

In This Land is OUR Land aka Justice, Dougé imagines a Pledge of Allegiance that resolutely and equitably protects its Black citizenry.

“I pledge allegiance to the flag that speaks to a holistic depiction of this country’s foundation. To a flag that pays homage and honors the enslaved Africans and their descendants. To a flag that acknowledges the contribution of Black people past slavery, mass incarceration, the hair industry to NOW and beyond. Justice represents our ingenuity, our resilience, our culture and our endless quest to be Free. She is You. She is Me. She is We. And this Land is OUR land too.”

By conjuring a new flag made by braiding dozens of bundles of synthetic hair, a product that is typically marketed to African American women, into a five feet by three feet revisioning of the American flag, Dougé troubles the notion that the icon is an infallible declaration of freedom. Red, white and blue is replaced by muted gray, black and brown stripes to represent and acknowledge Black contributions. The gesture offers a nuanced and clever query about the unacknowledged prevalence of Black labor, innovation and culture that has helped to establish the country as a formidable economic world power.

“Black bodies are political,” Dougé continued. “The very breath of our existence is political. There have been, and currently are, politics about and policies created specifically around our bodies and our capacity to live. To think otherwise is simply foolish.”

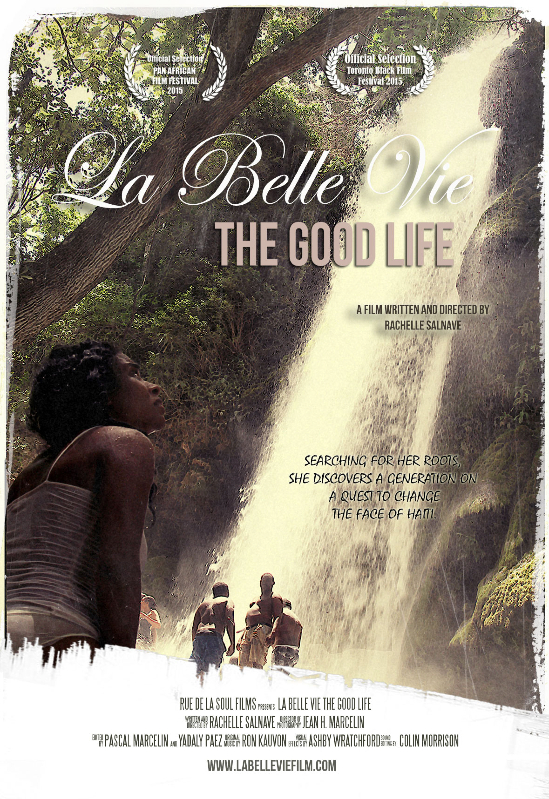

Speculative fiction and folklore also provide powerful possibilities for the revisioning and repositioning of monuments.

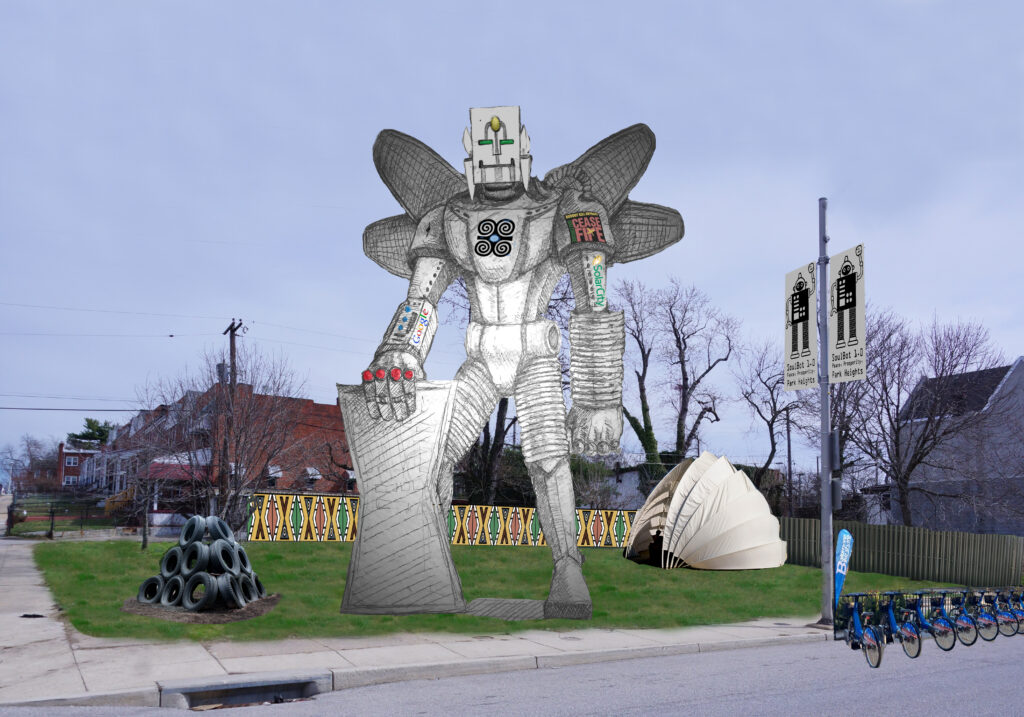

For the last five years, futurist and multimedia artist Jason Harris has been in the development and production phases of the The Blk Robot Project, an initiative that seeks to construct and install Soul Bot 1.0, a mobile 40-feet tall, metal African robot in Park Heights, a historically blighted neighborhood in Baltimore. The collaborative venture works with members from the community, educators, architects and engineers to design AI, aesthetic components of the robot and to develop curricula about the mythos surrounding Soul Bot.

“Artists create the iconography for movements, we write the songs and poems and stories, we enshrine the (S)heroes of these movements,” Harris shared. “Without art, both inspiration and cultural components to propagate movements would cease to exist. This project is a thought experiment designed to shift cultural perceptions and generate a new type of economic development in the community.

“Studies have shown that municipal development is overwhelmingly focused on central locales in cities, which results in the type of neglect that is evident in outlying neighborhoods such as Park Heights. More importantly, despite the disproportionate amount of resources, saturated areas yield lower returns on investments. Yet development agencies and institutions continue to rely on conventional strategies when turning their attention toward underserved areas that invariably result in displacement and erasure of communities,” Harris said.

Situating monuments as a means through which erasure is countered and memory is valued provides the platform for transformative actions that favor, rather than ignore, Black lives.

What radical possibilities emerge from the strategic designation and repositioning of historically erased subjects as monuments?

Landmarked, a multimedia series created by artist, educator and cultural organizer Ada Pinkston, seeks to answer the question: what does a monument for all people look like?

“LandMarked is an exploration of the architectural objects that we call monuments. Unearthing stories that are unheard about landmarks, monuments and the spaces of the city that are publicly and privately declared sacred,” Pinkston said.

Iterations of LandMarked consider history beyond its concretized mythos and place the narratives, memories and lived experiences of real people, who have been overshadowed by historicized figures, at the forefront.

“Through workshops, performances, and installations, LandMarked seeks to unearth memories and moments in history that are not widely known. Through this work, my aim is to democratize public memory through site-specific public artworks,” Pinkston added.

Writer Caroline Randall Williams’ recent OpEd in The New York Times about the personal implications of Confederate monuments offers a brilliant assessment of these times. “You want a Confederate monument? My body is a Confederate monument.”

If America genuinely wants to progress and evolve as a nation, it must begin to grapple with and discontinue all forms of systemic racism. The monuments that are slowly being removed today are not a true reflection of the grit, the determination or the genius that forged the country. Our bodies are the monuments. Protection of our lives should be paramount. When the nation chooses to dismantle, rather than pardon signifiers and active systems that inhibit equitable provisions for all of America’s citizenry regardless of race, gender, sexuality, religion or class, we will see lasting change, and the genuine realization of justice and liberty for all.