During his residencies with Black Rock in Senegal, Nnorom thought about the relationship of fabric to migration, immigration and the ocean.

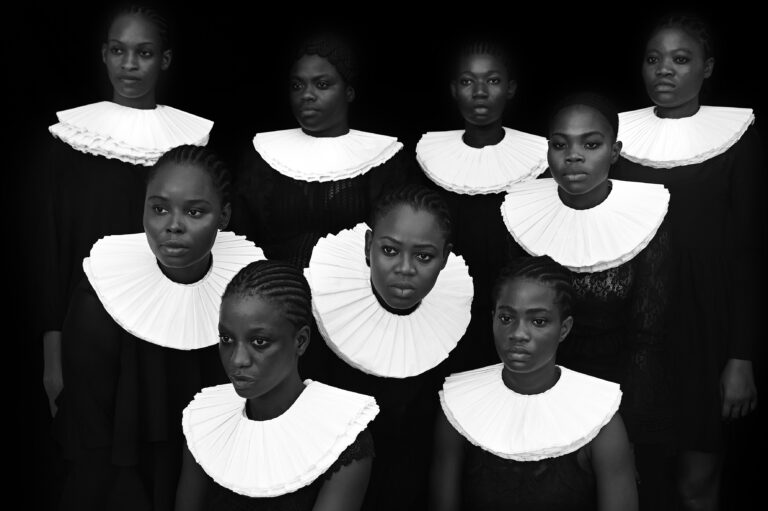

“Art for art’s sake” is a totally Western concept. It assumes art’s impact is drawn from aesthetic qualities. This ignores how an artist’s personhood shows up in their creative practice. Nigerian-born textile artist Samuel Nnorom summons the beauty and tragedy of the Black experience by weaving a story between Western consumption and environmentalism. His ornate textile sculptures dress walls like adorned canvases and encourage viewers to see his sculptures as metaphors for the fabric of society.

He most recently exhibited pieces at the Enter Art Fair in Copenhagen, Denmark with the South African THK Gallery. His work also will be represented by Kates-Ferri Projects at the 2024 Armory Show, New York. His art stands in many rooms around the world and sits at a critical point in culture where fashion meets fine art. His practice showcases Toni Morrison’s philosophy on art: “Art invites us to know beauty and to solicit it, summon it, from even the most tragic of circumstances.”

Nnorom’s personal story highlights his cultural context. His mother was a seamstress, and his father was a cobbler. Both of his parents nurtured his artistic skills by enrolling him in a crafts apprenticeship called Johnny Arts Production. After completing the apprenticeship, he taught creative art, embodied art and applied fine arts—painting, sculptures, graphics, performing arts, theatre and music—at Redeemed People’s Academy in Jos, Nigeria.

The through line of Nnorom’s teaching and practice is interdisciplinary art. He uses multiple techniques and builds a metaphor about society with Ankara fabric. Ankara fabric became popular in West Africa when it was introduced by the Dutch company Vlisco in the 19th century. Using culturally rich and recycled fabrics in his fine art empowers Nnorom to take up a generational torch and shine a light on fast fashion’s destructive relationship with the African continent. It’s more than destructive; it’s parasitic.

The world makes around 92 million tons of textile waste each year, almost half of which is plastic waste from synthetic fibers in polyester and acrylic. Even when framed as donations, fashion waste from affluent regions like North America and Europe—the Global North—ends up in Global South countries through a process called fashion waste colonialism; according to Oxfam, 70% of fashion waste lands in Africa. During his residencies with Black Rock in Senegal, Nnorom considered the relationship of fabric to migration, immigration and the ocean.

The themes of Nnorom’s work are linked to multiple cultures throughout the African diaspora, much like Ankara fabric. Ankara is accessible because it’s printed on cotton fabric, which makes it fit well into circular fashion and environmentalism since cotton biodegrades more easily than most fabrics. With textiles instead of texts, Nnorom has conversations about the magnitude of clothing waste from the Global North and how the secondhand clothing trade in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria can reframe an issue into something positive.

During our conversation, Nnorom shared insights into his practice as it relates to joy, fast fashion and environmentalism:

Lilac Burrell: What roles do textiles play in your lineage?

Samual Nnorom: From my place, my lineage, people from my particular region, which is Abia State in Nigeria, they are known as craft people. Crafts are something that runs from both my parents and where I come from. I find my identity in my lineage. Fabric seemed to be more relaxed, self-driven, and something that I found myself attached to after I started working with it. It got my attention at that point to try it and see how far it goes. I graduated from a secondary school in Nigeria, and upon my graduation, I worked as a studio manager. I worked for a year or two, then got admission into the university to study fine art. Then, when I graduated, I wanted, like every other person, to work in an official corporate space or a school. But when I was teaching, I felt there was something missing within me.

LB: What was missing, and where did you find joy?

SN: When I started feeling that emptiness. I applied for a master’s where I just did studio practice. I wasn’t having the opportunity to practice full-time. I think I needed to find my identity. What I thought growing up was people’s perception of art, but by working and teaching in art, I didn’t discover art myself. I was formally taught, and that was where I had the hunger for wanting to do more.

LB: When did Ankara fabric become a part of your story?

SN: The fabric is a material that’s largely consumed in West Africa. It shows a symbol of home in matrimony and identity. Because of the availability of the material, I went into research, and I was like, ‘okay, what could I bring into the art world?’ Knowing that this fabric is a predominant fabric in my community is a realization that whatever I find around me and convert into art is the process of going into its materiality.

LB: Can you tell me about the techniques you use in your practice?

By looking at fabric, it became, and I saw myself as a custodian. How do I maintain the quality of this fabric so that in the next 100 years, or 200 years, people can call back to it, find its originality and how it existed in this time? I use techniques of pulling metal, cutting fabric into shape, depending on how it comes, and then stitching it around at the edge. Using cotton fiber, used for making furniture; put that in, stitch it inside, and that makes an individual bubble. I now use the bubble as a way to stop history and as a way to describe people’s emotions, personality and what the cosmos goes for, for our existence. Most of the time, it comes in a very ephemeral state that keeps connecting and connecting and evolving until it becomes a matter that we can really feel and see. So for me, using the bubble became a way for me to describe the uncertainty of humanity and the Earth, thinking of how the temporal bubble would last. That was why I use the term bubble. Looking at fabric itself began to make more meaning from society.

LB: How do you feel about fast fashion?

SN: I’ve been concerned about our choice of fast fashion, handmade or crafted clothes. I did that idea for some of my residencies, like why fast fashion clothes are being consumed more in Africa and thinking about how Africa is a dumping ground for it. I think we here in Africa suffer much from this, from this consumption. It’s very difficult for you to find material like the politics and all that within the tele-workshops because they are produced massively from Asia and Europe and sent out to Africa. We have to start thinking about recycling. In most of my projects, I think about how these materials can be more artistic and used as art. Using secondhand fast fashion as an art material as opposed to wasting it in a landfill. Sometimes, I collect pieces from people to make social commentary art.

LB: What would be important to consider when reflecting on the human condition that’s illustrated through a fabric of society?

SN: It takes a community to raise a child, and thinking about the bubbles is a means in the metaphor to express the daily activity of teaching, sewing, twisting and studio activity. The bubbles are ways for people to communicate community while being mindful of community and how it’s brought people together, even after the pandemic, to show individual bubbles around fears and insecurities. The bubble represents people’s daily struggle to reunite.