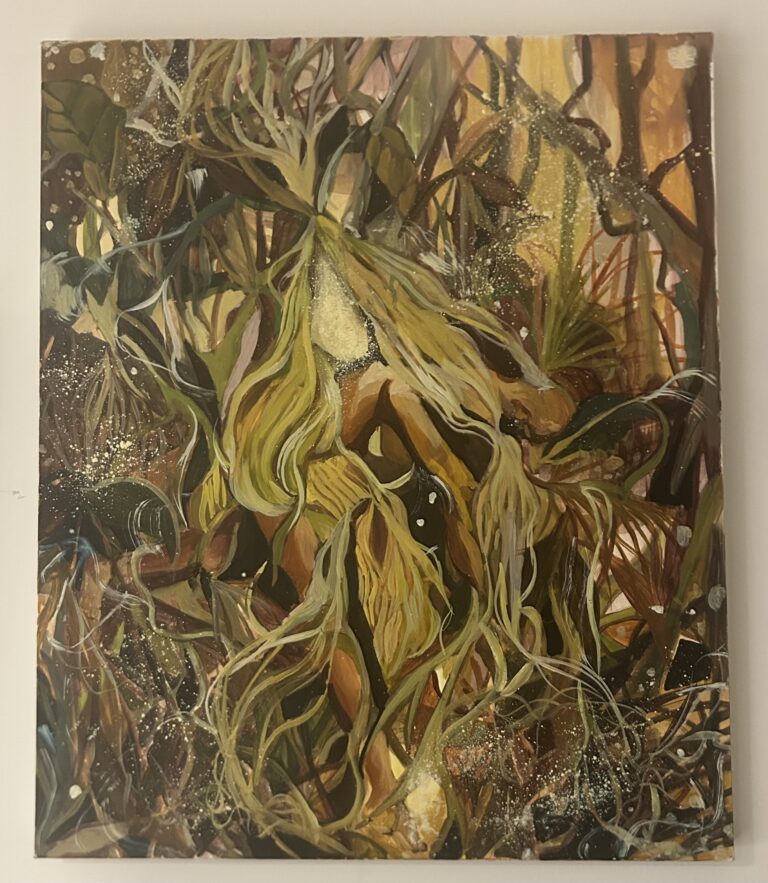

Above: Traces of Ecstasy, ICA at VCU, 2024, installation view

Earlier this year, The Institute of Contemporary Art at VCU opened a compelling exhibition curated by KJ Abudu entitled Traces of Ecstasy. The exhibition was inspired by an essay from queer exiled British-Nigerian artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode and adapted from a pavilion Abudu curated for the 2024 Lagos Biennial at Tafawa Balewa Square. Tafawa Balewa Square has a charged architectural and historical significance; in 1960, it served as a space to host ceremonies celebrating the country’s independence from British colonial rule. By staging the Traces of Ecstasy Pavilion at that site in Lagos and modifying it for American audiences at the ICA in Virginia, Abudu queries the contemporary conditions of the postcolonial world with a keen critique of the ideological legitimacy of the nation-state in and beyond Africa. For Abudu, “freedom-dreaming,” as described by scholar Robin D. G. Kelley, has been modeled by artists, theorists, freedom fighters, and intellectuals for generations and continues to offer us all a range of reparative possibilities by which to contextualize and resolve the myriad crises induced by late-stage capitalism. This notion guides the broad conceptual approaches of the contemporary African artists featured in the exhibition, including Nolan Oswald Dennis, Evan Ifekoya, Raymond Pinto, Temitayo Shonibare, and Adeju Thompson.

After three years of critical research, Abudu selected work that he believed “looked towards the past and the future.” The resultant interventions are exploratory, cerebral, and steeped in the rigorous discourses that inform our contemporary times. Featured artists activate indigo-dyeing techniques, masquerade performances, polyrhythmic drumming, and postcolonial modernist architecture and offer potent speculative meditations on digital sovereignty, fractal geometries, sonic healing, and queer embodiment. In addition to their formidable interventions, Abudu hosted The Traces of Ecstasy Symposium. This dynamic one-day symposium further contextualized the thematic and philosophical concerns undergirding the 2024 Lagos Biennial and ICA exhibitions. The symposium invited an international cadre of renowned artists and scholars, including Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Kwame Edwin Otu, Nkiru Nzegwu, Kevin Okoth, and Nkhensani Mkhari, to engage in a critical dialogue about their timely research reviewing colonial modernity, African indigeneity, postcoloniality, and the intersections of African metaphysical schemes and digital technologies. Their contributions provided an expansive recalibrating vantage to assess the exhibition and elevated the urgency of contemporary African art discourses in and beyond art historical canons.

I enjoyed attending an early tour of Traces of Ecstasy led by Abudu and ICA Curator Amber Esseiva. Afterward, Abudu and I had an in-depth conversation about the exhibition.

Angela N Carroll (AC): Why was it important for you to adapt the Lagos Biennial exhibition of Traces of Ecstasy for an American audience?

KJ Abudu (KA): Well, I’m very much grounded in Africa’s intellectual traditions and political history so I will always bring that with me wherever I go. But more importantly, this transatlantic recursion of the project in the United States is meant to articulate a fundamental idea that there is no “world” without Africa; the “world” as an aesthetic and ideological conceit depends on Africa’s material and metaphysical subjection. So, one cannot engage in a curatorial practice centered around Africa without articulating its entanglements with territories that exceed it. Africa is at once everywhere and nowhere. My practice aims, in the spirit of the trace, to reflect these conditions.

I am also always thinking within a Pan-African imaginary. So Africa, to me, is in the Caribbean, the Americas, Europe, and the Pacific. The artists I’m working with speak to this geographic expansiveness and exhibit a cosmopolitan, diasporic consciousness so the exhibition easily lends itself to an internationalist, constellatory logic. I’ve embedded such logics in previous projects such as Living With Ghosts, which occurred first at the Wallach Art Gallery in New York and then migrated to Pace Gallery in London.

AC: What was interesting about Richmond, Virginia, as a site for this exhibition?

KA: Firstly, Amber Esseiva is a curator that I’ve long admired, and I love what she’s doing at the ICA at VCU. Over the last few years, the program has successfully centered experimental Black and African practices that refuse narrow representationalist paradigms and exoticist expectations. So I immediately felt as though the ICA would be a great institutional fit for Traces of Ecstasy.

Historically speaking, Richmond is a very rich site to bring this project to given that the first enslaved Africans taken to the US arrived in Virginia. In my work, I’m always trying to map alternative coordinates within the space-time of colonial modernity, from the 15th century to the present. My hope is that the relay between Lagos and Richmond generates associative continuities between transatlantic slavery, the colonial capitalist infrastructures it birthed, and the formation of colonial states on the African continent.

Additionally, there are some important historical figures, such as the British-Nigerian artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode, who inform the transnational character of this project. Traces of Ecstasy is titled after a text Fani-Kayode wrote in 1987. I knew from the beginning that if we were to look at an artist like that, whose work was steeped in African Indigenous knowledge, but at the same time had these very unpredictable, cross-cultural energies that unsettled everybody, including Black British, Nigerian, and white queer people alike, then that had to inform the project’s queer, anarchic spirit. Richmond is also close to Washington D.C. where Fani-Kayode studied in the 1970s and where Tafawa Balewa (Nigeria’s first and only prime minister, who the site of the recent Lagos Biennial is named after) visited John F. Kennedy in 1961 shortly after Nigeria achieved independence.

AC: As you noted, the artists featured in this exhibition operate beyond the expected tropes of African art. Can you share what excites you about these artists?

KA: The artists and I have been in conversation for three years. From the beginning, in response to the biennial’s overarching theme of refuge, I knew I wanted to tackle ideas of nationalism and colonial capitalism through various media. I desired a maelstrom of sensorial encounters that would include sound, video, performance, sculpture, etc. So essentially, it was about finding collaborators working critically within various lines of aesthetic inquiry who fit the project’s decolonial, queer, anarchic orientation.

Adeju Thompson, the founder of the gender non-binary fashion label, Lagos Space Programme, was a no-brainer, even though they work outside of the conventional art world. I was drawn to their critical queer and futurist interpretations of various indigenous aesthetic traditions, from àdìrẹ (a resist indigo-dyeing technique) to the Gẹlẹdẹ masquerade (a masquerade ritually performed by male-gendered bodies in honor of female deities and ancestors.) Evan Ifekoya, who co-founded the UK collective, Black Obsidian Sound System, immediately came to mind for their capacious framing of sound as a ritualistic, healing technology and a catalytic medium for Black queer sociality. Their generative thinking for the exhibition around water’s state changes provides a poetic template for conceiving African political collectivity anew.

Nolan Oswald Dennis’s meticulous philosophical, scientific, and linguistic approach to questions of Black liberation, especially from an African continental perspective, proved crucial for Traces of Ecstasy. He had also been part of the the NTU collective with Tabita Rezaire and Bogosi Sekhukhuni, which similarly explored intersections of digital technology and African spirituality. His predilection for abstraction, systems-thinking, algorithmic logic, and fractality (grounded in African mathematical schemas), paired with his background in architecture, made him the ideal collaborator for designing the pavilion in Lagos and conceptualizing its recursion in Richmond. For the exhibition, Nolan also created a digital essay-game powered by a local browser that features a shape-shifting archive of texts, images, and videos grounded in the project’s conceptual pillars.

Temitayo Shonibare is a longtime collaborator whose interest in performativity and surveillance in the (always already racialized) digital realm introduced an unexpectedly humorous energy into the exhibition. Her multi-channel video work formed uncanny gestural connections between a variety of cultural sites in the Nigerian and Afro-disaporic media imaginary, from televised Pentecostal church services and Nollywood cinema to military parades and voguing ballrooms. And last but not least, Raymond Pinto is an incredible choreographer and artist whose movement-led thinking around notions of diaspora, ritual, and gender provided a rich, embodied entry point into the project’s themes. The series of performances Raymond developed for Traces of Ecstasy testify to the project’s core principles of collaboration and indeterminate becoming – every performance iteration was wildly different from the previous one and incorporated or activated aspects of other artists’ works, most especially, Adeju’s specially designed outfits.

AC: The artists you feature are also deeply invested in creating work that is critical and investigative and not just invested in aesthetic or ornamental representations of African culture. Do you think all artists, particularly those from the African diaspora, have a similar responsibility?

KA: I think there’s a possibility for an immanently critical aesthetics. In other words, for this project, I was interested in a form of artistic practice that embeds criticality in the work’s material performativity, in the aesthetic language of its political and historical interrogations. All the artists included in Traces of Ecstasy do that in a variety of ways, which makes their collective showing all the more exciting. But yes, I’m indeed interested in contemporary African art practices that rigorously deal with the structural predicament of our colonial present. That being said, we must be careful when using terms such as “criticality” because they often mask the operation of modern colonial discursive grammars. Sometimes what is actually critical (in an expanded sense) may appear, according to some anti-ornamentalist strands of Western thinking, as decorative.

AC: What do you hope people who view this exhibition walk away thinking about, troubling, or being inspired by?

KA: That everyone on the planet is implicated in the idea of Africa, both as a material reality and a discursive sign. That “queerness” and “technology” do not have a universal epistemological basis, especially when we consider alternative metaphysical constructions of gender/sexuality and techne offered by the global majority. That not only the capitalist mode of production but also the nation-state is a colonial instrument of expropriation and exploitation that is deeply implicated in the ongoing subjugation of contemporary (queer and indigenous) African life and ought to be abolished.

How might we articulate our desire for and model liberated modes of being-together that exist beyond the institutions of the state and capital? That, I believe, is the driving question for Traces of Ecstasy.

Traces of Ecstasy is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University from now through July 14th.