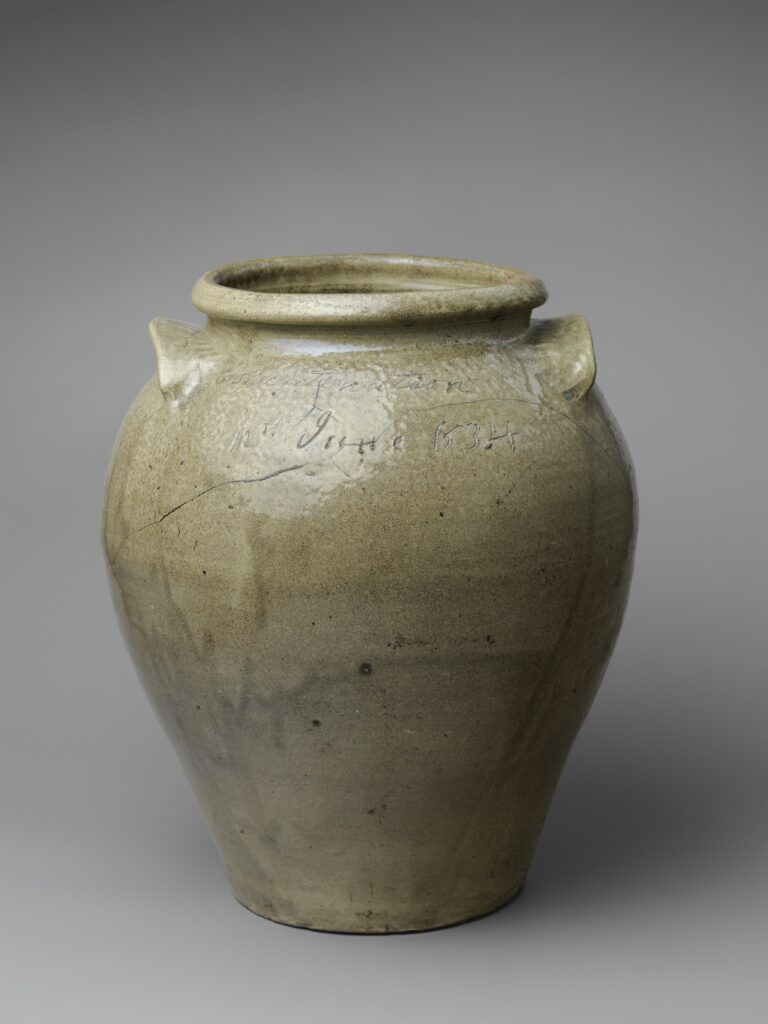

David Drake, best known as Dave the Potter, is featured in Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston. We know his name because of the hundred-plus pots that he inscribed from 1834-1864. Not only did his pottery have technical proficiency, but Drake fought against the enclosure that captivated him against his will: enslavement. Writing was illegal for enslaved people and a deliberate act of defiance and self-emancipation. Each stanza is a way of escape, a loophole of retreat. (Simmons, Nzinga | Simone Leigh: Loophole of Retreat | Art Papers (2019) https://www.artpapers.org/simone-leigh-loophole-of-retreat). Corey Depina even goes on to describe it as the ethos of hip-hop. It is a way of saying, HEAR ME NOW!

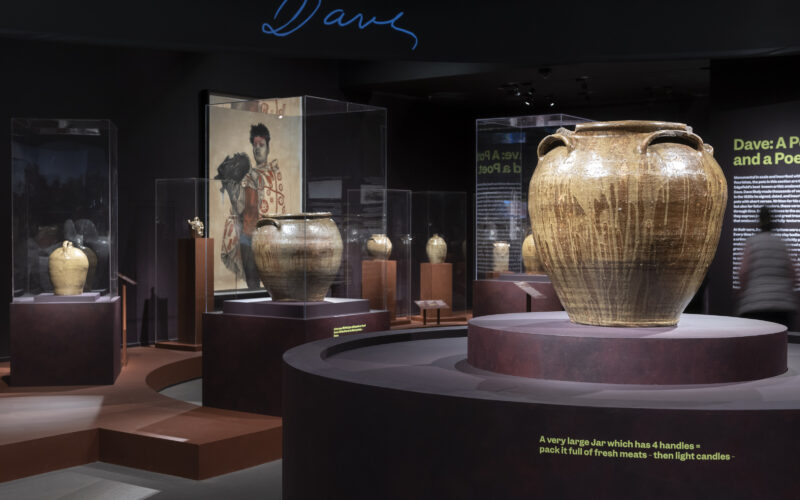

Therefore, the experience begins with audio, and there are voices, throughout, of Drake’s descendants, a video by Theaster Gates, the behind-the-scenes Table of Voices participants who shaped the exhibition, and the whispers of conversations between the pots. It features the names of many enslaved potters that are known. The main gallery is organized by duress, resistance and legacy. The first section of the gallery features fragments of broken pots, much like the history of many enslaved potters, pictures showing where Drake’s kiln was housed, slave cabins and jars made by “[blank line] potter once known.” This deliberate choice of labels by Jordan Cromwell, interpretive planner at the MFA, acknowledges our fragmented history but provides space to humanize the person and one day fill this gap.

The core of the exhibition is all about the resistance of Black artist David Drake. A large, circular monitor with animated cursive enlivens David Drake’s writing and frames a magnificent, large storage jar of alkaline-glazed stoneware. Its bulbous body, with four handles, sits at the center of the gallery. It once was packed full of salted meat to be preserved but now, ironically, serves as a preserver of Drake’s prowess.

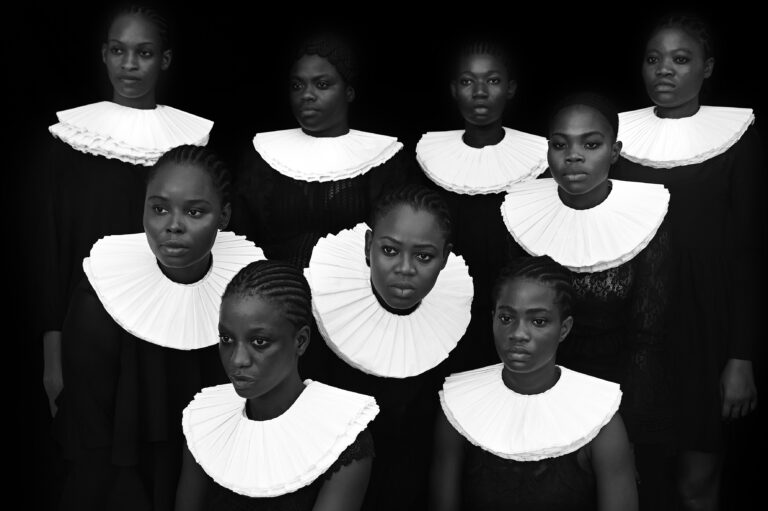

Lastly, Black contemporary artists respond to David Drake’s legacy: Theaster Gates, Adebunmi Gbadebo, Simone Leigh, Woody De Othello and Robert Pruitt. Simone Leigh’s Jug (2022) replicates one of her works featured in Simone Leigh: Sovereignty, her show as the first Black woman representing the U.S. at the Venice Biennale. The white of the vessel relates to the otherworldly, and the engorged cowrie shells on the exterior fuse the history of African currency and adornment with the Afrofuture. This is what David Drake and other enslaved potters only could have dreamed of. There also is a pairing of face vessels made by enslaved potters once known as having been paired with a Congolese nkisi figure.

What stands out about the exhibition is the sheen of beautiful glazes on all the jars in conversations with each other, the large-scale works coupled with smaller fragments and small face vessels, and ultimately, the mystical presence of all the work. For instance, kaolin was used for the teeth and eyes of the face vessels, which are believed to contain spiritual properties and communicate with the more-than-human realm. It provides a refreshing nuance and hybridity to the work of many of these enslaved potters: Christianity and West African cosmology fused.

The sense of care of the three curators, Ethan Lasser, the John Moors Cabot Chair, Art of the Americas at MFA Boston; Adrienne Spinozzi, associate curator in the American Wing, Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Jason Young, associate professor of history at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and David Drake’s descendants, who were present at Scholars and Lenders Day on March 31, is palpable. One of my favorite parts about hearing from them was realizing that we share the last name of Baker, and as I sat next to a woman named Danielle, a fifth-generation descendant of David Drake, the family was saying that we looked like we could be related; furthering Drake’s line: “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all and every nation.” (Farrington, Lisa | African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History | New York: Oxford University Press (2017) 42)