EXAMINING SURVEILLANCE, NATURE AND PARTICIPATION

Aldeide Delgado: To plan this conversation, I went to your Instagram account and looked for your last post to frame as a departure point for this interview. I found a post about Orange Functional—a project you inaugurated on June 25, 2022, in Art Omi, New York. It constitutes a participatory sculpture examining the power relations in public spaces for gathering and socialization. It is a piece that resembles another work you did back in 2004, The Garden of Mistrust. Considering you started your career in solitary in 2003, can you speak about the social and political context for creating these two pieces and what has changed, if so, in your trajectory between these two moments, 2003 and 2022?

Alexandre Arrechea: The Garden of Mistrust is the first project that I did back in 2003. Initially, it became a series, as I was unable to develop those works at the time, living in Cuba. The Garden of Mistrust is the first work of mine after I split from the artist collective Los Carpinteros. It addresses the preoccupations that I had at that moment: surveillance and its implications in the new society. I wanted to have the opportunity not only to address the issue from one single point but try to understand it as a whole. That’s how I started to develop the idea of the different trees. In fact, I developed Orange Tree,which is the first edition of Orange Functional and Nobody Listen, that is, a tree with ears. I was pointing at different issues and how participation with the artwork might change depending on the reality where you are.

I have to say that in the case of The Garden of Mistrust, it was influenced by the notion of being a Cuban citizen under surveillance at all times, with the difference that the surveillance system was neighbor-to-neighbor rather than technology. But when I traveled to London back in 2002, I discovered how the idea of surveillance was so big that you couldn’t actually hide. It was a wow factor for me.

It was like, “I’m not coming from the past, I’m actually coming from the future.” Because in this case, you are under surveillance all the time, so you behave differently. You have in mind that camera. You are like an actor, and you need to act in a way that corresponds to that character or not.

Orange Functional is interesting, because when I created Orange Tree, the first version, I never wanted people to play with the sculpture. It was about an aesthetic experience, it was the idea of gathering around a specific artwork that invites people to play with it, but at the same time, any playful action is forbidden. Carrying some frustration with it. I wanted to address the contradiction of being in front of a playful object and not being able to actually play with it.

But in 2020, I decided that it could be an exciting move to allow people to interact physically with the work, which adds a new level of understanding by implicating people in the conversation with the artwork but also socializing. At one point, I was talking about how the structure of the game through this particular piece is totally distorted, and you are baseless, because you don’t have rules to follow. It is about creating some kind of chaotic situation.

The idea of creating chaos, of losing the rules of the game, was something that, for me, was interesting when I created Orange Tree, but with this version now, I was looking at people playing with the artwork, and I realized how people immediately wanted to create new rules. That, for me, was interesting because, at some point, my experiment was somehow working. The idea of creating a work that resembles a specific game without rules and people immediately, in order to create a sort of coherence and relationship with that particular piece, they started creating rules and ways of playing with the work. This is a really beautiful and amazing experience and is something that, personally, I want to continue exploring through working with public sculptures.

AD: I’m very interested in artistic projects that can develop their own universe and activate themselves as organic entities. Departing from Orange Functional, we can speak about your whole career, because it addresses the central questions of your practice. I’m glad you mentioned the previous drawing of this sculpture, Orange Tree, created in 2010. Can you reference the relationship between your drawings and sculptures? Thinking about the process, they work as maps to announce possible worlds and unexpected associations that may seem impossible at first glance. Still, you have been able to take them to a real space as an actual monumental sculpture.

AA: Yes, absolutely. It’s interesting, because I’m always trying to bring a new element to the drawings in order to continue enlarging that map that I’m creating. Drawings, for me, have been like the core of my art production somehow. It departs from that idea in Havana back in the 90s, when you were unable to get or have access to materials, and drawing became the main way of doing things because it was also inexpensive. It was the easiest way, at least. All your dreams and ideas can be contained there. In a drawing.

Everything that I do, I firstly do it on paper. For my new exhibition, Landscape and Hierarchies in ArtYard, New Jersey, I’m introducing these new drawings that are under the title Monumental. This is based on the idea of how meaningful drawing is for me, and I can say for artists in general. But I’m producing these wooden notebook page templates. They are sort of the sculpture of a sheet of paper from a notebook.

Which I’m going to use for sketching drawings. Or perhaps sculpting drawings. It pays tribute to that whole trajectory in my career, working with watercolor and sketching constantly. It is about that conversation between the idea and the results of that idea, that connection between idea and the finished object.

Around two years ago, I came up with this notion. Because one of my goals is to shorten the distance between the rough idea and the end result, trying to bring them all to coexist, to create the possibility of both existing at the same time. I think you need a strong element to create a structure that holds the entire thing. It is the way the frame works on a painting. It enhances the painting. Well, this structure enhances the drawing, but it continues being a simple watercolor or pencil drawing.

AD: Have you considered including some immersive technology experience, such as VR, to interact with your drawings?

AA: I’m in the middle of that. We are not ready yet. But definitely, this is something that I am developing right now. I am developing the idea of creating, not specifically a drawing, but a situation that will allow people to draw whatever they want in order to bring new meanings departing from one specific experience that I am delivering to them. Landscape and Hierarchies is one of my most complete exhibitions so far, because it plays with so many different moments of my career during the last 20 years. People will relate to things that they probably have seen before, but they are shown in a way that they are totally new to them.

One of these crucial ideas is participation. Participating through the drawing is something that is highly important for this show. For me, it’s basic, but at the same time, I’m always trying to bring to the drawings a new perspective and possibilities, beyond the fact that it is an archive of ideas.

AD: I’m interested in the symbology of three natural elements constantly appearing in your work: corn, trees and gardens. What is the relationship between these elements, where including them in your work adds an organic materiality and the notion of surveillance, control and power that defines conceptually part of your practice?

AA: Many things definitely depart from personal experiences. For example, two weeks ago, more or less, my uncle Demecio Arrechea died in Cuba, unfortunately. But he is the one to blame for my adventurous spirit. I was an 11-year-old when he took me for the first time to the mountains just to grab food like bananas, avocados and mangoes. We arrived very early in the morning at this tiny little house on a hill where his friends lived.

There, they will offer you, obviously, in a very Cuban way, the early coffee at 5:00 a.m. in the morning. I was a kid; I barely drank coffee, but it was something that you had to do. My uncle told me, “Listen, drink that coffee.” The coffee is made with water taken from the river. They have this extended rope with a pulley and a metal bucket. From their window, they collect the water from the river and bring it back. That, for me, was already a thing. Like, the water doesn’t come from the faucet or the truck carrying water that comes to your neighborhood from time to time when you are running out of water; the water here comes from the river.

After drinking that coffee, we went deep into the woods, and my uncle left me momentarily in the middle of a forest, where I couldn’t see him or anyone. Imagine the impact of being by yourself alone, not knowing if my uncle is going to find me again. You experience anxiety thinking on finding the way to get out of that situation, but at the same time, I started to calm myself, like, “Okay, everything is okay, everything is fine. I have to trust my uncle.”

That’s when I started to experience the real beauty of that trip. I think that my uncle did it on purpose. He wanted me to experience all that. Being by myself, being alone. You don’t even know where you are, you don’t know where the next town is, or anything. But at the same time, you start to experience the idea, “In case I need to get out of here, I have to remember how we got here, which trails we took, etc.” To remember things, the map in your head.

That’s why for me, trees are so important. For instance, The Garden of Mistrust is sarcastic in the way of the surveillance system. You approach the tree, which in our history and in religion, is documented as the place to offer comfort. But at the same time, The Garden of Mistrust breaks that, and you don’t trust that situation anymore. Perhaps it departs from that experience in my mind as a kid, that connection. That’s why you’re always going to see the river; you are always going to see the tree. But you are also going to see the possibility of engaging with the objects I create. Because it’s about creating that possibility of dialogue, a space where you feel protected, but at the same time, you have to understand what’s going on with that specific thing you are in front of.

AD: Thank you for sharing this story. I have been reading a lot in the last month about Afrofuturism and how we can interact respectfully with other non-human species and the environment … I’m interested in this relationship with nature in your work.

AA: I forgot to explain the idea of fertility. Beyond the fact of having this corn with multiple seeds that implicate growing from there, I have developed this notion in The Map and The Fact. The yellow structure installed on the floor that resembles a plow field. It includes photographs of water, honey, sweat and blood. It is talking not precisely about that relationship between liquid and soil but about photography, sculpture, environment, history, etc. I try also to picture in my head that it is not only about that connection between one object and the other but what influence is bringing that object, with its own properties, onto the other, how it creates a different meaning, how you spark a different situation and create a new world out of that new relationship.

AD: Going back to Orange Functional, you have developed a universe of games, sports and toys through your work. You have been referencing football, ping pong, basketball and stadiums—thinking about how people use these places for socialization. This resource has been a way to expand the reach of your work, making it widely understandable to different audiences. But also, it’s a way to potentiate the participation of the receptor, making the artwork a live piece, like an organic tree.

AA: Referring to games in a ludic way is something that is embedded in me, that is already in my nature somehow, because when you are experiencing situations in which you have the familiarity of those elements that are on exhibit, you don’t have a barrier, you just go for it. There are no protocols. I see art, in general, as something that doesn’t need to be on a pedestal to be understood. You can play with language at a higher level, but there’s no need to express it with strange words. You just can use the basic words or the basic elements that we relate to daily. Perhaps that might be a better, or at least I think that might be a better way to enter that realm.

For instance, in Landscape and Hierarchies, I am using golf. One of the main installations is a landscape with trees out of glass. I’m taking the golf club, and I’m placing a GoPro camera on the golf club itself. The idea is that whatever you hit, it is recorded. This particular work connects so many different moments of my career in one single situation. I am creating a playful moment for people (they won’t be able to play with it, because the museum doesn’t allow it due to its glass elements and safety). But that’s what I want, people to experience the fear of playing in a situation where you can actually break the things and, at the same time, think about that in a bigger picture.

This is one of the most elaborated shows that I have done so far. It’s not in the amount of work. But it’s the dimension of it. It starts with the idea of what it means, the dimension of one gesture. I am in the river carrying water. I’ve been trying to pull people to that situation. I’m using that water to create a watercolor that is the largest watercolor I have ever done …

AD: You are going back to the water to make coffee.

AA: Exactly! Collecting water to create a watercolor is not something that is close to that particular context. I’m trying to expand that gesture to the entire town somehow.

For me, it is very important how we are dealing with elements of truth. I’m collecting this water, and I’m also recording the whole process through Polaroid photographs. I am presenting Polaroids along with the big watercolor to show the entire journey to create that work. But at the same time, I’m telling you, this is the truth about this; there is nothing hidden beyond this. But the way that the photographs are going to be played, I believe people will wonder if that is real or staged.

Landscape and Hierarchies is about turning ephemeral actions into monumental acts. But at the same time, the title for the watercolor is River and Ripples. It is the cause and effect, how one thing can lead to another one, and then it’s up to you to believe it or not.

AD: I love that you are adding that level of complexity by including the discussion about documentary photography and its (in)ability to show the truth.

AA: The drawing in itself is a landscape in which you are going to see myself collecting water from the river. But the way the line of the drawing has been crafted refers to the idea of the bleachers of the stadium. I’m doing a watercolor drawing, but I’m actually creating a stage, an architecture. It is the biggest stage. It is an immersive space where you can actually get into it like you are part of it. Depending on which side you’re standing on, that part of the drawing, that’s your point of view.

There is the desire of going back to basic elements of life: drinking water to survive. From there, how you can create this new world of relationships. I have John, my assistant at Artyard, and he is the one taking the Polaroids and documenting the process for me, and I told him, “Listen, I don’t have to be at all times with you for you to take the Polaroids. I want you to be free. I want you to take the bucket that I’ve been using for the water and place it in front of every house, every Plaza, every space here in the city, and take a shot of it.” Meaning that the gesture expands the borders of the museum.

When people come to the museum, they will probably recognize their house, garden, window, corner. It relates with the idea of the sublime, but at the same time, how I take back the resources of the language that I’ve been learning and put it in place in that community there and let them know that it’s not only about the art creation, but it’s about the attitude as a human being. Concerned with a given community. Where do you want to go, what is your offering, and what do you want to take back from me?

AD: Besides drawing and installations, a more performative part of your work can be found in video and photography, addressing the problem of race, labor, sacrifice, and the fight against yourself as your enemy. I’m thinking of Architectural Elements, White Corner, and The Face of the Nation. How do you understand this conceptual line of work within your creative practice?

AA: It is all about trying to move through languages that you normally don’t practice, but you are curious about it. For me, curiosity is what definitely leads to any investigation. Architectural Elements is one of those works that defines my practice. Everything comes from there. It is a photographic series about the role of the artist, specifically in the conditions of Havana, for this particular piece that has an evolution in my practice anywhere I go. It is based on the book, The City of Columns, by Alejo Carpentier, but in the photograph, you don’t see the face of the main column, that is, the human who holds the entire weight of the city on its shoulders. You definitely are familiar with the idea of being stopped in Cuba by the police, especially in the 90s, living there and being harassed at all times.

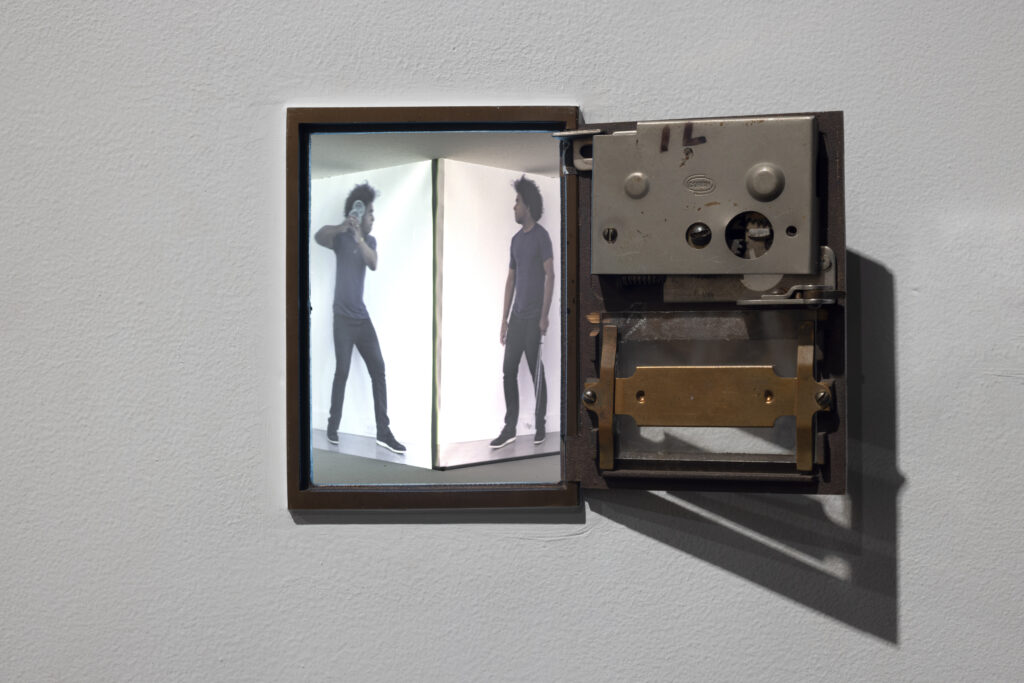

White Corner is even more complex because of the idea of calling it white instead of any other color. Obviously, the corner is white in itself. There is reference to the white cube, reference to skin. It is this idea of being contained by that other structure, and you are trying to defend yourself from that. White Corner is one of those works done on video that involves so many different layers. It expresses the failure to recognize the similarity in the otherness. In the new version that I present in Landscape and Hierarchies, you’ll see the artist struggling one more time, but this time it’s using many of the elements present in the installations in the gallery. I’m using the golf club, the glass trees … I’m using all the elements that I have produced to create the entire show. I’m using them all against myself one more time.

AD: To end, I would like to ask, what are you dreaming of now? Any future plans?

AA: My dreams continue being big. One of the things that are now becoming important, if I can say that, is the idea of collaboration with other art expressions. Right now, I cannot talk about it, but I’m planning collaborations with the dance world. I’m extending my arms and opening myself to new experiences in that sense. I want to continue pushing boundaries. Next year, I’m celebrating my 20 years as a solo artist. So that is meaningful. I’m still here, I’m still hanging, I’m still producing. I want to continue doing bigger and better.

The exhibition Landscape and Hierarchies is on view at ArtYard through Jan. 22, 2023.