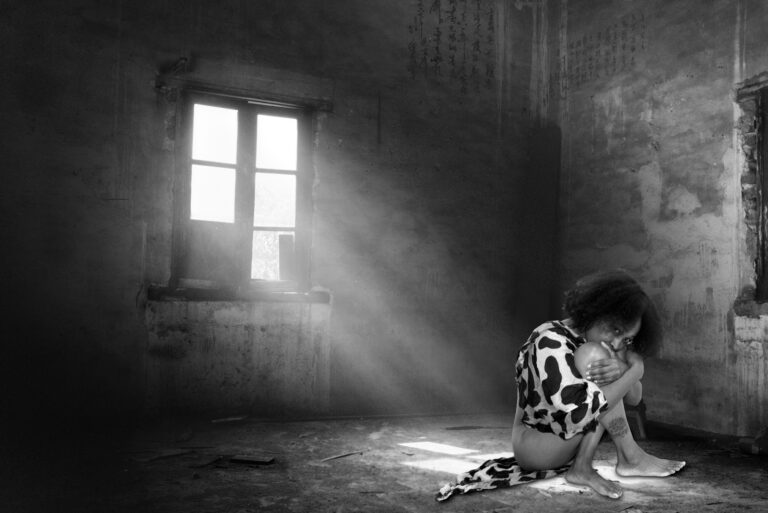

Above: Alexis Alleyne-Caputo, Portal © 2022

Alexis Alleyne-Caputo has a vision of what’s possible that we badly need in our white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalistic, colonial world. Brought together by years of lived experience and work as an interdisciplinary artist, anthropologist, educator, and researcher—it’s a vision of resistance, a vision of light, a vision of empowerment, a vision of collective consciousness. Hers is a way of focusing—an awareness—a recognition of possibilities for minds, bodies, and hearts to come together in new and uplifting ways that goes beyond the visual through Caputo’s unique ability to use one sensory input to stimulate another cognitive pathway.

I first noticed this ability in Caputo’s spoken-word work. Listen to a piece like Hear Her Roar, and the visions, the feels will be immediate. As I began to engage with the six photographs highlighted here, Caputo’s visual media bring up in me not just visual but auditory sensations. With more time, these sounds began to congeal into songs. Songs by artists I see giving a related vision to Caputo’s. Given her vision and her desire to “provide a framework for dialogic engagement,” I proceed by putting Caputo in conversation with some such musicians.

—–

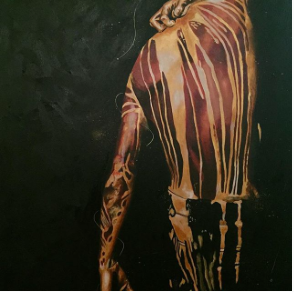

One way to see Skin, Ink, & Concrete is as the foundation upon which the series is built. The photographs come together to create a vision of resistance and revolution. Among others, one primary target of Caputo’s resistance is what the late Charles Mills called “white ignorance.” As Mills argues, “white ignorance … plays itself out in the complex interaction of Eurocentric perception and categorization, white normativity, social memory and social amnesia, the derogation of non-white testimony, racial group interests, and motivated irrationality.” In every way, this photograph provides healing in response to the harms of white ignorance.

Both artist Caputo, and subject Alana Marie Duhart, being Black women (with Duhart being biracial) provide an antidote to Eurocentric perception. Their composition challenges white normativity and celebrates Black excellence (and testimony). It also celebrates another form of combatting white ignorance and an underappreciated form of protest—graffiti.

As Mills has shown, the horrifically white supremacist world we live in requires us to lie to ourselves constantly and to avoid saying certain things. So, graffiti becomes an essential tool for reminding us that those things are lies, for saying the unsayable. Caputo’s juxtaposition of graffiti with Duhart’s tattoos also provides a framework for seeing tattoos as a form of epistemic resistance. For more on these reframes, it’s instructive to put Caputo’s work in dialogue with Mr. Lif’s bars from the Thievery Corporation song, Ghetto Matrix—especially the hook, “It’s on you, it’s your mind. It’s a complex plan that keeps us confined.”

—–

Another layer of Caputo’s vision is added with Portal. In addition to continuing Caputo’s ability to conjure up sounds with sights, Portal introduces her ability to create time and motion in what is usually thought of as a static medium. The perspective through the repeating arches gives a sense of moving through time. The model, Angie Gervais, acts as a compass throughout this journey, seemingly both grounded and flying in the photograph.

Importantly, not only do her feet point us to the future, but her locks remind us to look to the past in the ways we move toward the future. Here, one is reminded of the important roles that Black women’s hair has played in Black resilience, from personal and cultural expression to keeper of seeds and lifeways during the Middle Passage (as Leah Penniman said in the Ayana Young podcast, Deeply Rooted June 23, 2020). Yet again, we see a resonance between the visions of Caputo and Mr. Lif, this time from History—“Remember Nat Turner the rebellious slave. He’s well known because he misbehaved, or, rather, he behaved in ways that aligned with his people’s freedom.”

—–

This historical grounding and the most striking visuals are provided by Infrastructure. Caputo puts black-and-white photography to use—drawing our focus to Desiree Parkman and the light emanating from her body. Combined with her posture (she’s quite literally bending over backwards), the scaffolding around her and the title, Infrastructure, serve as a stark reminder that this country was built on stolen Black bodies and labor, stolen Indigenous land and life. In fact, it’s hard to not see this piece as the series’ thesis—Black women as light, as key to liberation.

Given the historical role that Infrastructure plays, it’s also a good reminder of the lineage of Black women scholar-artist-activists upon whom Caputo builds—giants with whom she studied and by whom she was empowered, like Deborah Willis and Angela Davis. Caputo’s contributions can clearly be seen as continuing a conversation on Willis’ course, “The Black Body and the Lens.”

Caputo’s experience studying with Davis on her Blues Legacies and Black Feminism also provides further motivation to put her work in dialogue with musicians. Several Black women musicians doing similar work preceded their solo careers in the supergroup, The Sorority. We see a similar uplifting of the labor and light of Black women in their song, SRTY—“So tell me why you can’t respect that? You tell us eat because we skinny, and stop eatin’ when we’re too fat. We’re never good enough, hood enough, light enough. Always trying to dim us ‘cause some dimwit just ain’t bright enough.”

—–

Chroma provides a complementary counterpoint to its predecessor—still providing us that vision of Black women as light—but doing so with color photography, and this time, with model Roodjine Saint-Aude, standing and facing the viewer. It’s as if she stands up proudly and says alongside Phoenix Pagliacci (from her collaboration with Mohawk musician DJ Shub) in The Social—“This is my truth, you can’t take from me. It’s not just how I feel, it ain’t make believe. Until you see the world through my Black eyes, you can only speculate about our Black lives.”

Uplifting Caputo’s desire to create dialogue and her highlighting of Black women’s positionality, I’m reminded of my own standpoint as a white cisgender man here. I know that, in a white supremacist and patriarchal world, I won’t be able to know what it’s like to live and see the world as a Black woman. Furthermore, the Combahee River Collective statement reminds us, “Black women are inherently valuable … our liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else’s.”

Still, I see both Caputo and Pagliacci as challenging me and others with different identities to be in community with Black women in ways that show us that centering Black women has revolutionary potential for us all. As the Combahee statement made clear, “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

—–

Penetration returns us to black-and-white and more of Caputo’s conversations with earlier generations of Black women scholars-artists-activists. In a mostly dark room, Cheryl Harrell is the light. With our attention drawn to her by the sun and with us being drawn into space by the black-and-white method, Harrell’s eyes being on us is notable. It recalls the late bell hooks’ work on the oppositional gaze. Rebelling against an oppressive world that denies Black people’s (especially Black women’s) right to look, Harrell and Caputo join hooks in declaring, “Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.”

bell hooks’ pen name being an honoring of her great-grandmother also highlights the intergenerational nature of community and liberation work. This motivates the thought of scholar-artist-activist Claudia Ford, who has been developing the concept of grandmother epistemology. This is the idea that Black and Indigenous ecological wisdom, often cultivated, held, and passed down by grandmothers, contains models for being, doing, and knowing that we want to honor, center, and uplift for a just, sustainable, equitable future.

This uplifting of intergenerational, epistemic, political work can be heard from Racquel Jones (like Caputo and Mr. Lif, with Caribbean roots) in Letter to the Editor—“Cause our bombs dem metaphoric. We talk Di truth and mek Di youths dem better for it. Cause I’m a fighter, yeah. If you agree put up yuh lighter, yeah.”

—–

As difficult as it is to bring this complex and dynamic series of sights, sounds and conversations to a close, Rising is up to the challenge. The futuristic architecture and water bubbles carrying a diversity of African diasporic peoples, styles, cultures and genders place Caputo’s work in conversation with the Afrofuturist movement. Once we see this, there is no need to bring these conversations to an end. As N.K. Jemisin has made clear, recognizing “how terrifying it’s been to realize no one thinks my people have a future,” part of the point becomes continuing the conversation and “… spinning the futures I want to see.”

Alexis Alleyne-Caputo makes poignant contributions to this continued conversation. To further the discussion, I encourage you to visit alexiscaputo.com and leave you with powerful words from Sault’s Black Is—“We all know Black is beautiful. You know, well now you do, Black is excellent too. In me, in you. Black is shiny and new. Black is older than earth. All at the same damn time … Don’t be afraid. We can make a change and we can make it different.”

Matt LaVine is a writer, race equity facilitator and racial justice activist based out of what is now known as Portland, Oregon.