Above: Gideon Appah, The Older Couple, 2021. Oil on canvas. Photo: Adam Reich

Forgotten Nudes Landscapes, the latest exhibition from mixed-media artist Gideon Appah (born 1987), currently showing at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University (ICA VCU), explores the utopic possibilities of culture, community and our collective imagination. For some of us, the club, the theater, the corner, the stoop is a safehouse, a space to see and be seen by community, to learn cool and to inspire cool. For others, the solace of the body is a landscape, a site to observe the self, to contemplate the ego and the id, and the constructs that inform our worldviews.

ICA VCU curator Amber Essevia selected key works created by Appah between 2020-2021. Many are early works inspired by Appah’s pre-pandemic observations of everyday people, including several paintings from the 2020 solo exhibition at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, Blue Boys Blues. Other featured works were rendered during the height of the pandemic and represent a drastic shift in Appah’s style.

“The show is set up in a very sequential order,” Essevia shared with this writer. “When we started the conversation [about a commissioned project] with Gideon in Fall 2020, at the time, he was working on a series of paintings thinking about night life and leisure as it relates to Ghanian night life and culture, as well as popular theaters that were open at the time.“

Cool is a culture and a commodity. Growing up in Accra, Ghana, Appah was influenced by material culture and mass media imported from the West, including film, printed matter and music. The bodies of work that Appah produced in 2020 were informed by his observations of idealized beauty and cool on post-colonial Ghanian culture.

“His works are really in the vein of Malick Sidibé or Barkley L. Hendricks; artists who are thinking about this notion of Black cool and leisure at a time where [Black] people are not portrayed as being at their best, or their best dressed,” Essevia continued.

In Appah’s early works, utopic landscapes are envisioned as portraits that compound real people and imagined cultural icons into chic, stylized terrains placed front-and-center in otherwise non-distinct scenes. By making the environments less prominent, viewers are left to meditate on the mood evoked by the placement of the figure in the scene.

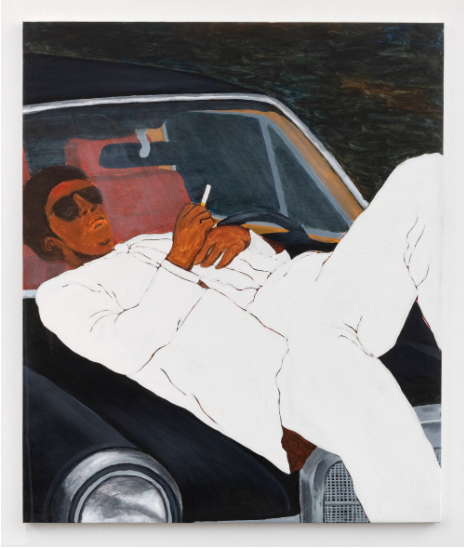

In Hyped Teen (2020), an oil and acrylic on canvas, Appah conjures a potently nostalgic and iconic image. A young Black man dressed in an all-white suit reclines, cigarette in hand, on the hood of a luxury car. Appah activates a tight frame reminiscent of album covers or classic American cinema. Black cool is focalized and subtly accentuated.

Above: Gideon Appah, Hyped Teen, 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas. Photo: Adam Reich

Like notable fauvists, Appah’s painterly employ of exaggerated color and light emphasizes the energetic beauty of his figures without reliance on the exacting tropes of realism. Remember Our Stars (2020), an oil and acrylic on canvas, is a seminal example of Appah’s early style. The aesthetic he explores in this period reviews the sublimity of communal joy as a utopic landscape.

Above: Gideon Appah, Remember Our Stars, 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas. Photo: Adam Reich

In Remember Our Stars, six men, dressed only in white underwear and socks, grin as they look over their shoulder towards the viewer. The men’s skin tones are highlighted by bright blues, pinks and oranges. Their posture reminds onlookers of burlesque dancers or strippers. As is common in other portraits from this era, the sites that the subjects occupy are nonspecific, except for a curtain of stars that fill the background, which reads more like a stage than a celestial dimension.

In the rare instance that recognizable landmarks or imagined utopias are included, the inverse is applied—the referenced site becomes the focus and subject—a forefront character that establishes the mood or vibe in the scene. In Roxy 2 (2020-2021), an oil and acrylic on canvas, Appah references the front façade of The Roxy Theater, one of several movie chains erected in Accra in the mid ‘40s-‘50s by Ahuma Ocansay, a gold coast merchant and investor.

In the portrait, a crowd of men in crisp suits communes together, illuminated by the neon pink glow of the Roxy Theater sign. In another work, White Castle (2021), an oil on sewn canvas, Appah imagines the skyline of a distant cityscape that stretches across a night horizon. Stars twinkle above the skyline and reflect in a sea of stars. The landscape is the subject, and our attention is fixed on the beauty of the cityscape, even though the depicted vantage point does not exist anywhere in Ghana.

In contrast, later works developed by Appah while in isolation during the pandemic explore the sublime as a subconscious landscape. Works created in deep isolation at the height of the pandemic are starkly different from earlier portraits; figures are less pronounced, and the environment commands more of the viewers’ attention. Appah intentionally redirects our gaze; with no figure to review, we are forced to approach the work from a more psycho-spiritual space, ruminating on our own mortality and our own identities separate from community.

Where sites and subjects cannot be reviewed, Appah’s patina shifts. He applies a muted tone to the landscapes and diverges from the white suits and neon luminescence of site and subject in early works.

Above: Gideon Appah, Black Beast, 2021. Oil on canvas. Photo: Adam Reich

In the diptych Lonely Stallion (2020-2021), an oil and acrylic on canvas, and Black Beast (2020-2021), an oil and acrylic on sewn canvas, a singular horse centers each portrait. The horses are depicted grazing or standing in desolate fields while dark clouds loom above in the distance. These seminal pandemic works emphasize isolation. Appah’s use of darker patinas—dark brown, black, gray and blood red, invoke thoughts about those lost to the COVID-19 virus, as well as the depression or mental health crisis that many who were sequestered experienced. Unlike his earlier works, with these representations, Appah asserts a world where strength is situated as an apocalyptic, lone horse, a perseverant and hopeful totem in uncertain and trying times.

Forgotten Nudes Landscapes also feature a selection of new drawings and a rare collection of paintings from Appah’s Death of the Theater series. The drawing series and the Death of the Theater series reference other divergences from the more colorful aesthetic that Appah has been recognized for.

In the drawing series, Appah utilizes charcoal to illustrate still-life portraits of deconstructed sitters—dismembered hands and feet, skulls, wilting flowers. The series also features illustrations that are more grounded in the realism of traditional portraiture, as well as elegantly rendered landscapes. The fragmented figures are reminiscent of the symbology that one may encounter in an oracle or tarot deck. The Death of the Theater series continues this theme, a reference to the surreal and the symbolic to query space, time and figuration by melding portraiture and landscape traditions.

In all iterations, the curiously cryptic and beautiful vantages that Appah insists we explore inspire an introspective assessment of our conscious and unconscious realities.