For her debut exhibition with the gallery, Cassi Namoda (b. 1988, Maputo, Mozambique) presents a new series of paintings that were created in Cape Town, South Africa and in East Hampton, New York, where she currently lives and works. The title, Tropical Depression, is both poetic and ambiguous. It is partly inspired by lived experience (a bout of illness while working in Africa) but also the destructive power of nature (a tropical depression is another word for a cyclone). Equally, it speaks to recent Mozambican history and the links between colonialism, war and the status of women. This interweaving of personal and historical references is typical of Namoda’s practice.

Several of the paintings on view were conceived in Cape Town, where Namoda confronted the theme of the nude for the first time. A key starting point

for understanding the emotional thrust of these images is Mozambique’s decade-long struggle for independence (1964-74). Like a geological fault line, it splits history into the colonial and post-colonial eras. Unlike her mother and grandmother, who lived under Portuguese rule, Namoda was born into a newly liberated society. For her generation, the colonial past is something that can only be accessed through words, testimonies and images. And yet its impact is immense and all pervasive. This duality — between past and present, colonialism and post-colonialism, Africa and Europe, spiritual traditions and

a globalised world — is a latent force in this new body of work, which not only seeks out visual metaphors for this turbulent period in Mozambican history but also a means of articulating and processing its legacy.

One of the principal visual sources for this series is the work of photo-journalist Ricardo Rangel (1924-2009), who was also born in Maputo, the country’s capital. The paintings revolve around Bar Texas, a venue in downtown Maputo that attracted a mixed clientele in the 60s and 70s. Extensively photographed by Rangel, the bar is a recurrent motif in Namoda’s work, a visual metaphor for a place of ambivalence, the backdrop to good times and bad. Creating

a cinematic-like narrative, the individual paintings resemble film stills within a broader, almost universal narrative. The entwined partners also call to mind the contemporaneous Bob Dylan song Mozambique (1975) from the album Desire — ‘all the couples dancing cheek to cheek, it’s very nice to stay a week or two, there’s lot of pretty girls in Mozambique’ — and all this might imply. The women have a distinct and assertive presence, with certain physical details volumetrically elaborated, compared to the ghostly men, who are only provisionally rendered. This creates an interesting interplay between painting and drawing, light and dark, further emphasising the distance between the partners despite their physical proximity.

Self loathing in 100 percent humidity is an inverted translation of Rangel’s photograph Reed City — Chamanculo (1961). By recreating the scene in paint, Namoda connects an African odalisque with the great European tradition of the reclining nude, with obvious references to Manet’s Olympia (1863). Only the black woman is no longer a servant (as in the French painting) but the protagonist. Namoda’s nude is inscrutable and enigmatic: is she master of

her destiny or at the mercy of it? In a collapsing of time and space, Self loathing in 100 percent humidity conflates the all-pervasive issues of race and prostitution (also an important discourse in relation to Olympia), as well as the male and female gaze. In a further allusion to European art history, Self-Sabotage at 3am in the Early Mornings, Thunderous Bangs is a recapitulation of Gauguin’s monotype L’Esprit Veille (1900) — a work that was also based on photographs. In her painting, Namoda appropriates and re-contextualises Gauguin’s dark and predatory imagery, one that is steeped in exoticism and colonialism, thus allowing it to be reconsidered in an alternative, more relevant and contemporary context.

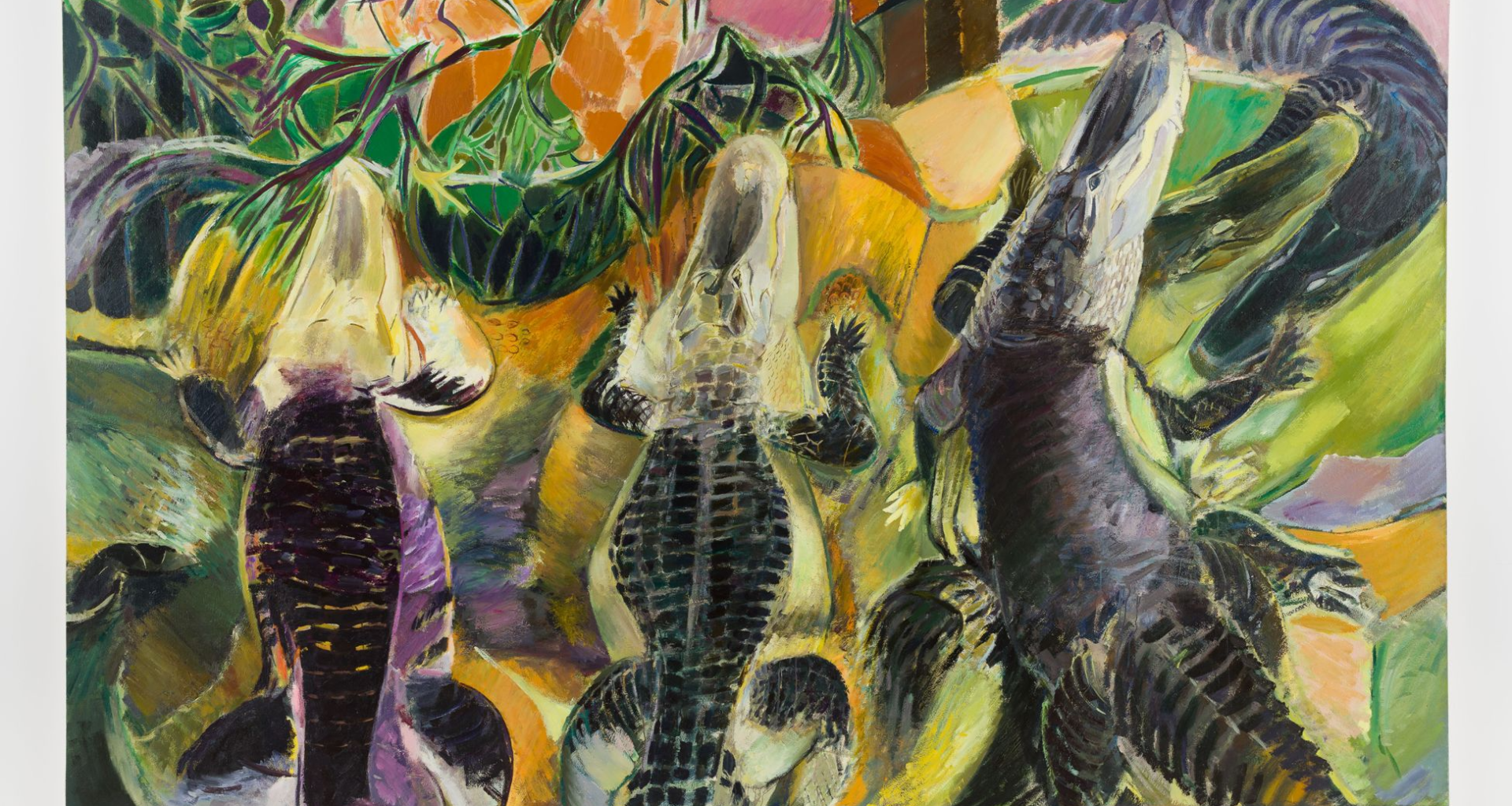

While the cool, restrained palette in the above works chimes with the historical period, the paintings executed in the United States are brighter, with back- ground colours organised into more complex bands, grids and quadrants.

The introduction of Christianity as the majority religion by the Portuguese, an important aspect of Mozambique’s history, is invoked in High Malaria, Maria’s Respite. Another key work in this ensemble is High Malaria at the Witching Hour, which directly references Arii Matamoe [The Royal End] (1892), also by Gauguin. Whereas the original work depicts King Pōmare V’s severed head on a pillow, Namoda in turn paints a woman smoking a cigarette. In his collage book Noa Noa (1901), Gauguin described the king’s death as a metaphor for the disappearance of native Tahitian culture at the hands of Europeans. In the woman’s severed but seductive head, we see

a layering and overlapping of African and European history and visual cultures, as well as the powerful themes of violence and sex in the colonial era.

Cassi Namoda (b. 1988 in Maputo, Mozambique) lives and works in East Hampton, New York and Los Angeles, California. Namoda’s work has been included in exhibitions at Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, New York; Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, New York and Library Street Collective, Detroit. She is included in girls girls girls, currently on view at Lismore Castle, Lismore, Ireland. Namoda’s work is held in the collections of Pérez Art Museum, Miami; Studio Museum, Harlem; and the Baltimore Museum of Art. In 2023, she will be a resident at Thread Senegal – Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.