Above:Betye Saar, Gliding into Midnight, 2019. Mixed media assemblage, 144 x 180 x 180 in. Tia Collection, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Image courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles.

When I view an archival image of Oasis (1984), an installation of blown glass spheres situated around a child’s rocking chair embedded in the sand by mixed-media artist Betye Saar (b. 1926), originally staged at The Museum of Contemporary Art; I can hear the ocean. Thirty-plus years of life come roaring back into fragmented memories from my youth, thoughts about family, and liberation. White sand. A bright sun refracts against my shea-buttered skin. I am shining in the light—smiling as I imagine the future, transfixed by a seemingly endless blue horizon. I come back to the present, trying to remember the last time I felt safe here—genuinely free. I return to the ocean, crashing against my petite frame, my strong stance refusing to fall.

To be Black in the world is to feel constant tension—a tightness in your muscles, clenching anticipation that never completely subsides. Even in moments of unabashed joy, there is a knowing that white-supremacist, illogical pathologies will attempt to disrupt your peace—microaggressions, bigoted violence, trending loops of unprosecuted slaughter. If every part of a person’s life is an oasis, as Saar proclaims it can be, we all may find some refuge in the intimate nostalgic respites Saar reveals.

For over 60 years, Saar has scoured and reassembled refuse into meditative interventions, immersive installations, venerated altars, and object-laden collage or assemblage constructions. In all iterations, the worlds Saar builds are created with the highest intention and an immense curiosity to understand who we are by reviewing the material culture of who we have been. Saar is drawn to the resonance of objects, the residual imprints or essence that remains after the object has traversed countless lives.

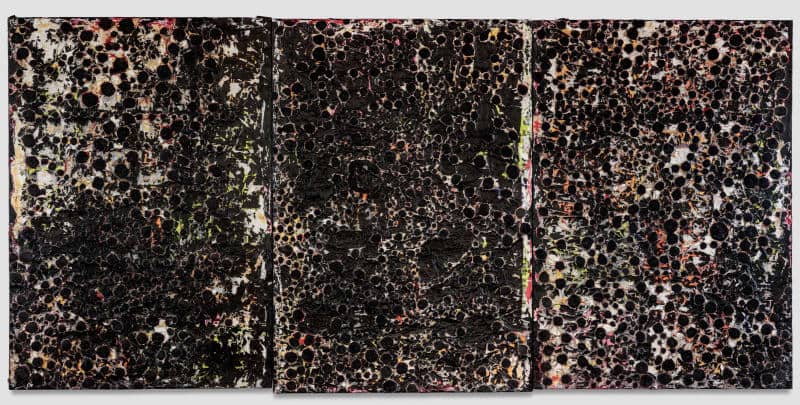

Above: Betye Saar, Mojotech, 1987. Mixed media assemblage, 76 x 294 x 16 in. Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

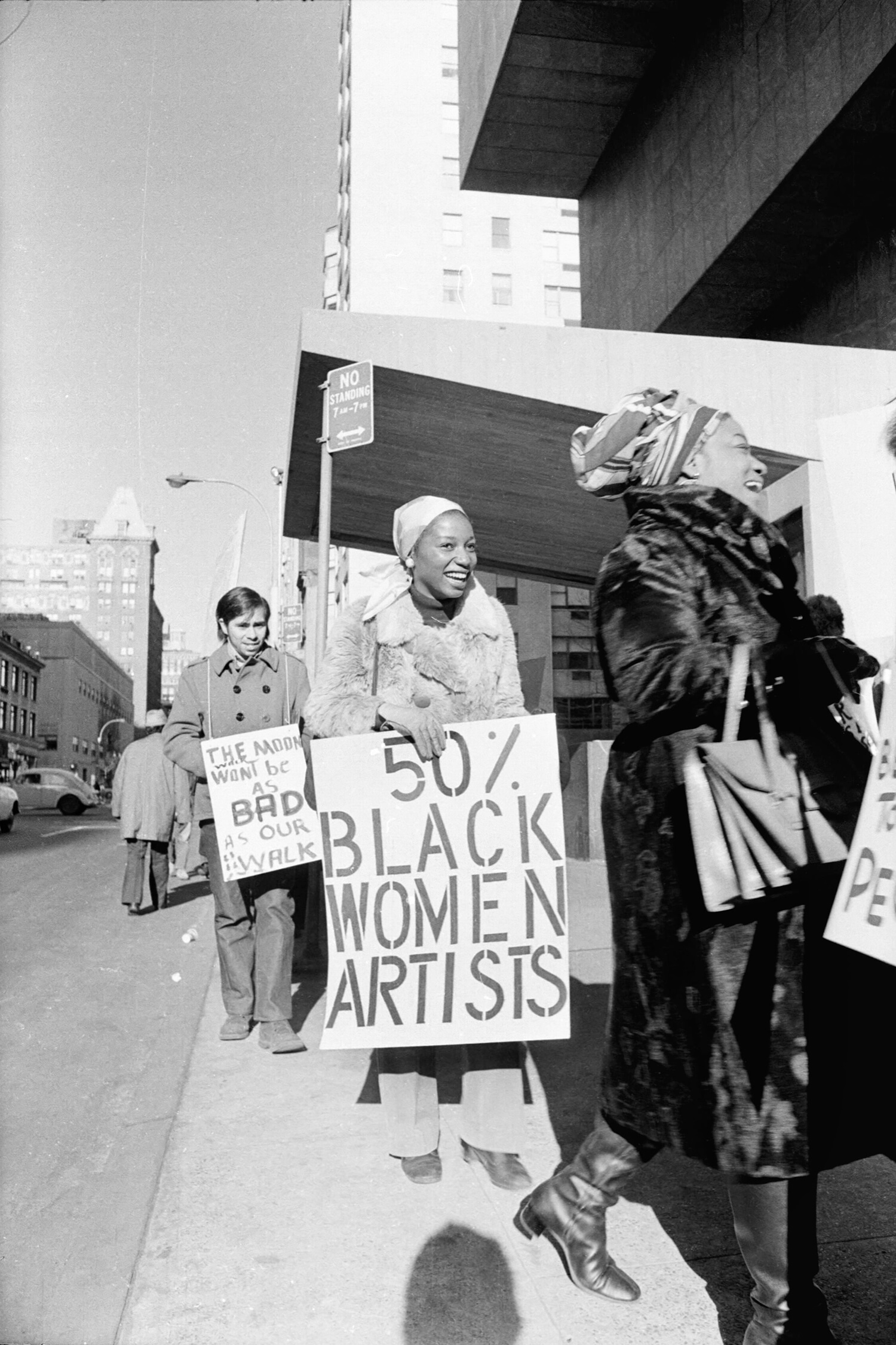

This year, the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami will exhibit the first survey of rarely seen installations created by Saar over the last 30 years. Curated by Stephanie Seidel, Serious Moonlight reconfigures large-scale installations that mark significant periods of inquiry and experimentation in Saar’s practice. When commenting on Saar’s narrative approach, Seidel noted, “Through these rarely seen installations, made nearly three decades ago, the exhibition illustrates her bold and pioneering approach as an artist, storyteller and mythmaker, and the ongoing significance and relevance of her work to the most pressing issues in America today.”

Oasis (1984) is included in the exhibition among other significant works including House of Fortune (1988), Limbo (1994) and Wings of Morning (1992), Mojotech (1987), Secrets and Shadows (1989), A Woman’s Boat: Voyages (1998) and Gliding into Midnight (2019), which will include fragments from the 1993 installation In Troubled Waters. In all iterations, the works within Serious Moonlight continue to showcase the exquisite curiosity and prolific artistry of one of the most dynamic 20th century American artists of her generation.

Saar describes the act of making art as “a ritual,” which this writer likens to an alchemical process that involves a procedural set of acts. “The imprint—ideas, thoughts, memories, dreams, from the past, present, and future; The search—the selective eye and intuition; The collecting—gathering, and accumulating objects and materials, each bringing a presence, an energy; The recycling and transformation—the materials and objects are manipulated and combined with various media, and the energy is integrated and expanded; The release—the work is shared, (exhibited), experienced and relinquished.” When the set of acts are fulfilled, Saar considers the ritual to be complete.

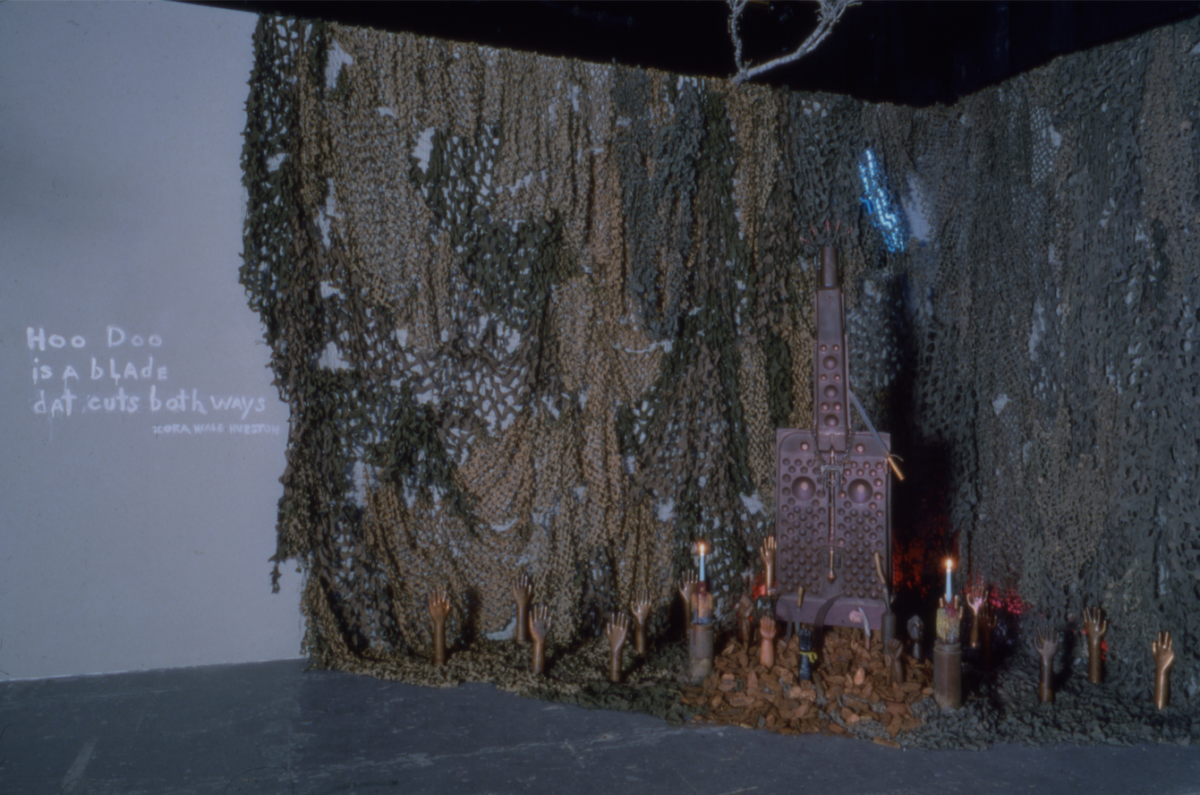

Above: Installation view: “Limbo: A Transitional State or Place,” Santa Monica Museum of Art, 1994. Image courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles

Saar activates and is activated by an intuitive and attentive process deeply tied to her spiritual studies. Ancient traditions inspire her; Haitian Voodoo and American hoodoo, African traditional religions, and metaphysical systems including phrenology, astrology and palmistry. She is perpetually gathering—staying alert to the pull of other objects and open to the imagining that will eventually become a tangible work. The objects she gathers are in some ways familiar but otherwise foreign to her, newly encountered, stumbled upon and salvaged. Once an object is obtained and added to her extensive inventory, it is stored until its usefulness is more pronounced.

“I remember reading Arnold Rubin’s Artforum article in 1975, Accumulation: Power and Display in African Sculpture, in which he talked about how certain materials in African art have power and other materials are just for display or to help reinforce that power. That was a strong influence on me. Once again, it goes back to my intuition—’mother-wit’ or whatever you want to call it—about selecting materials that possess power,” Saar disclosed in an interview conducted via correspondence with this writer.

“Rubin described how the borders around a rug are used to protect the inner area. If it is sacred—for instance, a prayer rug—then the inside of the design is the sacred part, and the fringe is there to prevent negativity from entering that inner area. I found that very interesting. If you’re making an assemblage, there’s power in a certain part of the piece, and then all the rest is decoration, either to throw off the negativity or to attract positive feelings. That’s how I felt about my boxes or collages: the sacred element is located in a particular place in the composition; the rest is just display, used to entice the viewer to look at the work,” Saarwrote.

By rendering new mythos from classical archetypes and instinctively feeling her way towards found objects that will eventually substantiate new works, Saar asserts ancient ways of being as valid methodologies. As such, Saar’s practice clarifies strategies of resistance that rupture expected—linear, taught—ways of being, making and discovery.

In 1990, Ishmael Reed conducted an interview with Saar (Saar Dust (1990) for The Art of Betye and Allison: Secrets Dialogues Revelations exhibition catalog) to discuss her practice. When asked if the work involves chance, Saar responded, “This is an important part of the work, the element of risk, the element of the unknown, like that’s where the spirituality comes in, you know, like trusting the spirit to guide you through.” The unknown, what Saar also describes as the mystery, is an exploration in discovery; the unearthing, renaming, and assertion of value to that which was previously lost, forgotten in the annuls of thrift stores or the litter of sidewalks.

Above: Betye Saar, Snake in the Heart, 1987. Sequins hand-applied on cloth, 27 x 14 1/2 in. Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Black cultural memory is often discarded. Saar’s reclamation of found images and family photographs, segments of quilts, glass beads or ancestral keepsakes is a subtle defiance—a refusal to be erased or singularly defined. A declaration that rejects what Michelle Wright conceptualizes as qualitative collapse the crisis of modernity, the need to simultaneously deny and exploit the labor of Blackness by situating it within linear and limited notions of spacetime (what Wright asserts as the collapse of meaningful, layered, rich and nuanced interpolations that occur when seeking to assert Blackness through linear spacetime).

Instead, Saar’s work envisions the continuity of Black presence in the world by exemplifying what Achille Mbembe clarifies as an interlocking of presents, pasts and futures, “that retain their depths of other presents, pasts, and future, each age bearing, altering, and maintaining the previous ones (On the Postcolony, by Achille Mbembe).”

Who have we been? How have we preserved our history? Saar’s quest to unveil the creative potential of obscure ephemera is a transformative gesture—an attempt to elevate subjects—both theme and personhood—from the violence of being discarded—considerations that literally and figuratively identify people or objects as waste. When asked whether institutions should do more to ensure that unsung artists are included in their collections and exhibitions, Saar noted, “Yes, of course, they should. If a museum collects American art, it should also include African American artists. As well as Asian American, Hispanic American, Middle Eastern American and Native American artists. There are many ’American’ artists. We are all American.”

This desire to see and encourage others to accept an expanded conception of practice through a diverse appraisal of topics that remain relevant 30 years after their construction substantiates Saar as an inspiring, relevant and masterful genius. A review of her astounding career in any form is a momentous and revelatory occasion.