Above: Sheryl Dickey with Historic Sistrunk installation. Courtesy of Downtown Photo

The Sistrunk Corridor is an historic African American community in the northwestern quadrant of Fort Lauderdale. Like much of Florida, the Black residents of Sistrunk hail from across the diaspora and bring with them diverse cultural perspectives that over time, have cemented the culture of Sistrunk. Sistrunk’s first Black settlers came from the Bahamas, Georgia, and northern and central Florida. Sistrunk’s culture was birthed from its early settlers, who in the early 1900s developed their community west of the railroads where many worked. Over time, this community of sharecroppers opened businesses and churches, built homes, and established social clubs.

As many communities undergo cultural shifts, given gentrification and its migratory and displacing effects, an exhibition about Sistrunk stands as an example for documenting people’s social history. The exhibition, The Porch is the Tree is the Watering Hole, is on display through May at the African American Research Library and Cultural Center in Washington Park, Florida. The show weaves together art, architecture, photography, and poetry to the story of Sistrunk, and more broadly, of Black communities. Often, elements of legacy have gone overlooked by traditional historical exhibitions and academic efforts of documentation. In the curatorial approach to this exhibition, the fictional and the imagined pair well against the more historical and narrative-driven works and texts.

The title of the exhibition is an excerpt from a poem by Darius Daughtry, who is featured in the exhibition. The porch is a basin for cultural continuity; it is shaped by its sitters, who braid, who laugh, who pass on tradition and share history. Across the African diaspora, porches remain a staple where public and private lives are blurred, where intimate conversations occur, and intergenerational exchanges manifest. In this interview, curator Dominique Denis shares more on her vision for the exhibition and affinity for Black communities.

Above: Laura Novoa, left, and Adrienne Chadwick. Courtesy of Downtown Photo.

Above:Artist Adler Guerrier with Untitled (Sistrunk—in medias res. Unfurling the presence of Black life.) | Adler Gurrrier | 2020 | Courtesy of Downtown Photo.

Maleke Glee: For an outsider, how would you describe Sistrunk?

Dominique Denis: Sistrunk is an historical Black neighborhood located northwest of downtown Fort Lauderdale. During the 1940s, 50s and 60s, this bustling commercial and residential neighborhood was the epicenter of Black life. While the community is currently facing many challenges, its history and culture remain some of its most valuable assets.

MG: Forced migration and gentrification are threats being faced by Black populations globally. Is this a concern for the Sistrunk community?

DD: Yes, Sistrunk residents are facing some of the same challenges most Black communities are faced with when it comes to gentrification and its impact on marginalized communities. Throughout our urban exploration of the neighborhood, it became clear to us that we might be documenting a way of life that is forever changing. Hopefully, the exhibition will help bring new interest to the preservation of Sistrunk’s cultural and historical heritage.

MG: This exhibition blends together architecture, contemporary art practice, and modern approaches to historical documentation. As a curator, I appreciate that there is something for a diverse set of interests. Why were all these elements necessary to tell this story?

DD: While developing the overall concept for the exhibition, it became clear to me that the overall narrative needed to be experienced visually, emotionally and spatially. The poetry by Darius Daughtry, the historical installation, and the pictures from David Muir’s exploration of the neighborhood help the viewers engage with the exhibition at a personal and emotional level. The work of Germane Barnes, especially his introduction of the shotgun home into the overall narrative, determines how the exhibition is experienced spatially. The work of the other visual artists and designers, Adler Guerrier, Adrienne Chadwick, George Gadson, Olalekan Jeyifous, Marlene Brunot and Dillard Center for the Arts students, in their diversity, were able to enrich the overall experience.

MG: It is beautiful to see your background in architecture foregrounded in this exhibition. How did you arrive into curatorial practice? How do you view architecture and design in relation to the art world?

DD: I started working for the Cultural Division at a time when I was reassessing my career in traditional architectural practice. However, the overall concept for the exhibition is still grounded in my architectural training. The way people relate to the built environment has always been something I am interested in, and being able to explore it with this selected group of artists and designers was a wonderful experience.

Nowadays, there are a lot of cross-disciplinary collaborations between architects, artists and designers, and the lines between the disciplines are often blurred. When it comes to public art, I always encourage the artists I am working with to use the design tools and presentation techniques that will help them achieve a successful collaboration with the design team.

MG: Can you tell me a little more about the community engagement, the involvement of high school students, and how the community shared their images for display?

DD: Back in 2018, 15 Dillard Center for the Arts students, under the supervision of their art teacher, Mr. Celestin Joseph, participated in a workshop organized by one of the artists commissioned by the Broward Cultural Division. Artists commissioned to design an artwork in the Sistrunk neighborhood are often required to conduct workshops with members of the community prior to developing a design proposal. The students were given a list of words such as serenity, home, peace and safety to use as inspiration to create two-dimensional drawings reflecting their aspiration for the neighborhood. Each one of these drawings was incorporated into the artist’s final sculpture, which can be seen at the Dillard Green Space, a park near their high school. Both the original drawings and three-dimensional representations of these drawings are showcased in the exhibition.

Above:Where we Gather | David I. Muir | 2020

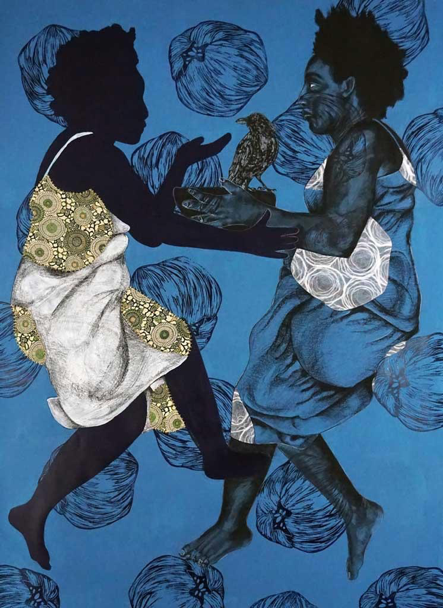

Untitled | Germane Barnes | 2020

Uneasy Lies the Head that Wears a Crown | Germane Barnes | 2020

Historic Sistrunk installation. Courtesy of Downtown Photo.

MG: The diaspora is referenced heavily in the design throughout the exhibition, represented through architecture and more abstract symbols. How do you arrive at connecting the African diaspora in the works displayed?

DD: The Black artists who were invited to participate in the exhibition were from different parts of the country and the Caribbean. You had these Black artists reflecting on the state of an historical Black (but mostly African American) neighborhood. While some might decide to focus on the diversity of the Black experience and how culturally diverse the African diaspora is, I wanted the exhibition to constantly remind us of our roots and common history. That is why many of the installations are making reference to Africa.

For more information about The Porch is the Tree is the Watering Hole exhibition, on display Thursdays and Saturdays through May 29, visit www.artscalendar.com/sistrunk