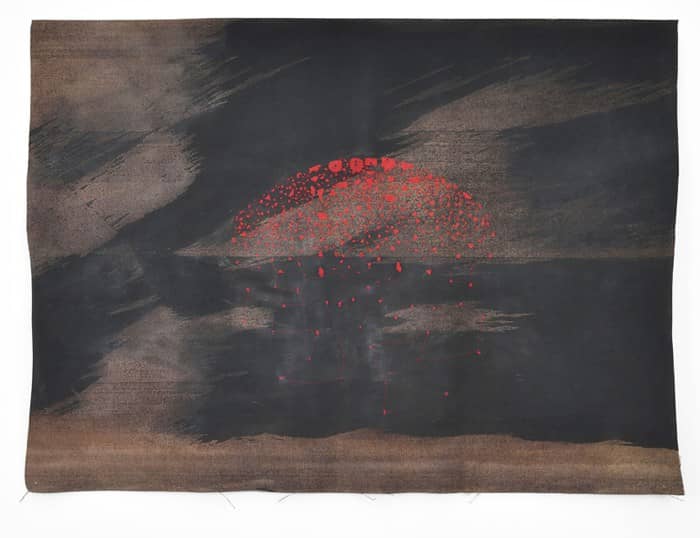

Above: Raje for President by Renee Cox

Renee Cox isn’t about the bullshit: she is sharp and unapologetic about the subjects she channels. Cox uses her body as a conduit: a small axe chopping at the brittle branches of false and exclusionary histories. For the last 30 years, the prolific photographer has posed for more than a thousand portraits and exhibited hundreds of images within series that have come to define late 20th century portraiture.

In all iterations, Cox’ work champions Black narratives; the known and unknowable chronicles of Black presence in America and the Caribbean. Her portraits have no limitations: Black people are gods, superheroes, Maroon freedom fighters and sacred Madonnas.

Even Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben are evolved by her reimagining of their likenesses in Liberation of Aunt Jemima & Uncle B (1998)as superbly Black superhumans who are adorned in the unforgettable patina of Black liberation. This gesture, an unabashed declaration that Black bodies exist in the past and will exist in the future, is a powerful strategy, a mindful apparatus through which our collective imaginations can be recalibrated to dismantle and eradicate the fragile constructs of overwhelmingly flat and historically racist propaganda about Black lives.

“There is a permanence to photography,” Cox shared during a brief Zoom interview. “a longevity…. And sometimes I like to think of it as creating my own propaganda. It’s an immediate vehicle.”

Humans are hungry for legacy. World histories have proven time and time again that to be Black is to have a precarious life expectancy; white supremacy is a longstanding pandemic that refuses to be acknowledged as such. History is marked by the slaughter of Black lives, innocents and rebels whose mundane lives or rally cries for civil rights resulted in execution.

What was Breonna Taylor’s crime? What was it about her resting body, weary from serving as an essential worker during a pandemic, that warranted her assassins to consider her, and her family, a threat? She died like Chairman Fred Hampton: no knock, bullet riddled, while asleep in her bed. And like him, those who murdered her remain free. Black life is only variably recognized as human. Histories of photography provide an important lens into the fodder that feeds pathological fears about Black presence and hopeful possibilities about its usefulness in decolonizing our collective imaginaries.

Since the advent of modern photography in the early 19th century and well into the contemporary moment, non-white bodies have been the peculiar fetish of the white gaze. As anthropological inquiry or pseudo-scientific eugenic proofs, the photography and surveillance of Black bodies has served to found inimical categorizations and biases that posit Black lives as gross deviations from whiteness.

When you do not control your image-making, the skewed portrayals that caricature your likeness and culture will be used to sustain your subjugation. Othering, as it has been perpetuated via still and moving images, remains an enduring psychic and physical violence against non-white bodies; a normalized flattening engaged to justify injustices that would otherwise be considered unconscionable.

When I asked Cox what motivated her to feel confident enough to use herself as a model in thousands of portraits, her response was concise and inspiring. “Self-love,” she nodded affirmatively. “I have not had an overnight success, it has taken years, decades, but there is always that element there. I never had any kind of inferiority complex. I’m always available to myself, and it makes the message clearer and more authentic.”

In 1862, abolitionist Frederick Douglass was also hopeful that photography, a burgeoning technology, would be a useful tool to recalibrate and humanize imaginaries about Black identity. During the address, Pictures and Progress delivered in Boston on December 3, 1861, Douglass noted that “man warms, glows and expands only where [he] sees himself asserted—broadly and truly.”

For Douglass, as written by scholars Maurice Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, “the formerly enslaved could reverse the social death that defined slavery with another objectifying flash: this time creating a positive image of the social life of freedom.” The predominant images of Black life that dominated 19th century media and discourses situated Black bodies as docile, half-witted and hypersexual burdens in need of white stewardship.

When your identity is satirized, stereotyped, and signified as trite commodities for mass consumption, you have to search and struggle to see yourself beyond the limits of those inculcations. Douglass allowed himself to be photographed over 100 times during his lifetime: he was affirmed by the belief that the redundant image of his audacious dignity would provide a powerful counter-narrative to otherwise narrow assessments about Black identity.

“Since the beginning, I’ve only been interested in doing images that were uplifting,” Cox continued, “and I’ll use the word propaganda again, because I want little girls to look at it and go, ’I could do that!’ or ’I don’t have to be afraid to do that.’”

May 20, 1962: Minister Malcolm X stood on the pulpit of a crowded church and readied himself to engage an equally eager and skeptical crowd in Los Angeles. “Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet?,” he queried. The profound irrefutability of his question challenged all who could hear him, then and now, to trouble and assess the ideologies that found and uphold civil injustices against Black Americans.

Our imaginaries about the past, present and future are informed by the pedagogies and propaganda we consume. History is propaganda. Advertising reinforces a paradisiacal ideal about American culture and erases the gritty realities, the violence, the forced free labor, the rape, the perpetual murder of Black lives, the systemic suppression of Black rights, the continuous disappearance of migrant children and women, the fear and moral condemning of non-gender conforming, queer and trans lives, and the persuasive push for all who can to assimilate into the code of behavior of whiteness propagated by illusions of racial hierarchy.

Advertising is never neutral: it is a calculated propaganda. That is why, 131 years after its founding, The Pearl Milling Company, now known as the Quaker Oats Company of Chicago, a subsidiary of PepsiCo., is just now considering the violent implications of its most beloved mascot, Aunt Jemima; a passive, ever-smiling caricature of Black feminine servitude.

Who is served and who is subjugated by photographic and illustrative renderings of obedient Black, Brown and indigenous laborers? How do those images influence our collective imaginaries about the value and humanity of their bodies?

Cox spent the early half of her career as a highly sought-after editorial fashion photographer in Paris and New York. Her work from this period was stunning, but far from radical: the images reified conventional standards of wealth and beauty. Her presence as a tenacious and talented woman photographer was radical; the field of photography then and now is dominated by white men. And to be Black and a woman in that prodigiously competitive position made her a unicorn. Though the work was profitable, including a lucrative tenure at Essence Magazine, her growing political consciousness was frustrated by the apathy of her colleagues about domestic and international movements for Black liberation.

“I was like, I’ve gotta get out of here because… what’s my legacy? I shot the most beautiful models back in the 90s? My kids are gonna look at that and go, yeah, but, how shallow.”

From then on, Cox was determined to use her own body as a brazen model; a testament that refused erasure. Black portraiture is a mutiny against histories of portraiture that only consider Black and Brown bodies when they are in service to a white aristocracy.

“After having lived in Europe for quite a while and going to homes there, you would see… oil paintings of one of their ancestors, and they would know all of their ancestry, and [those portraits] would be hung prominently in their homes. And I was like, shit, if you grow up with that, it gives you a whole sense of yourself.

“But, when I visited a lot of Black households, we weren’t getting that. You’re getting these little photographs. No scale. No seven-foot photograph of somebody. That’s why a lot of my work is big. It had to be big. It had to be in their face. I had to let them know that I exist, and I exist in a big way, not in some secondary, pushed-off-to-the-side kind of way.”

We are more than mockery and martyrdom. Cox renders a canon of portraiture that is founded in love; a deep and unflinching adoration of Black people and a resolute mission to render inclusive historical accounts. She documents the persistence of Black brilliance that endures despite the bloodlust of white supremacy: an illogical ego-driven anxiety that is not satisfied unless it incites and inflicts violence on all it categorizes as Other.

That is why so many, including former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, took emphatic offense to one of Cox most iconic portraits, Yo Mama’s Last Supper (1996), a series of five color coupler prints, flush-mounted to aluminum. In the work, a nude, dreadlocked Cox signifies Christ. She holds her head high and stares beyond the suspicious and enchanted gaze of her 12 disciples. Everyone in the image is melanated.

This courageous depiction advocates for representations that align with the bronzed, wooly haired descriptions of biblical verse. The blond-haired, blue eyed Christ of Leonardo Davinci’s imagination that dominates popular culture and Western art is erased, decentered, and replaced by a cadre of beautiful Black and Brown subjects.

Much of the polarizing response Cox’s work has received over the years is a deep apprehension about the accountability and creative liberty her work demands.

Whether Cox is conjuring Raje, the long lost sister of Wonder Woman in Chillen With Liberty (1998) and Lost in Space (1998), embodying Queen Nanny, an 18th century revolutionary Jamaican Maroon leader in Warrior (2004) and Mother of Us All (2004), or revisioning the signing of the declaration of independence with an all-Black delegation in The Signing (2017), she consistently dismantles and challenges longstanding presumptions about how Black bodies, and Black women, should be positioned in history.

The burden of respectability that has been placed on people of color and femme-identified bodies is cast off. Her work situates and celebrates real and imagined women and elevates them with affirming and empowering portrayals.

“It’s about creating and controlling our imagery, and then mak[ing] it clear.” Cox continued, “I’m too old to be running around protesting with signs, but I definitely want to have the conversation, the discourse, in order to try to make a change… the imagery, it plays a big role.”

When asked about critiques that she has received from other women about her use of nudity, she offered an uncompromising rebuttal.

“To me that’s a simple reaction to having done fashion and basically saying, I give you my authentic self. You can’t class it. You can’t say I’m this [or] I’m bad. I’m thinking this way. How much more pure can you get? [The portraits] are not sexual, in my opinion. They’re not giving you like, Oh, come fuck me. [laughs] It’s just like, no, this is who I am. That’s it.”